Month: April 2023

MMS • Almir Vuk

Earlier this month, Uno Platform released Preview 5 of its plugin for Figma, offering enhanced features for designers and developers. The latest version of the plugin allows the creation of custom colors, eliminating color limitations, and enables the import of Design Systems Packages (DSP) for sharing design system information across various tools and designs. Additionally, new controls such as Pips Pager and TabBar with vertical orientation, as well as the ItemsRepeater feature, offer even greater flexibility to create highly dynamic and interactive designs.

Uno Platform has introduced new features that provide users with enhanced flexibility in managing the themes and colors of their apps. These features empower users to customize their app’s visual appearance and tailor it to their unique preferences and brand identity, resulting in personalized and visually appealing user experiences.

The significant new feature is the Design System Package (DSP) importing, which allows users to create and save custom material color palettes that can be easily imported into the Uno Figma plugin to quickly change the app’s theme. This feature streamlines the process of applying consistent colors across different designs and layouts, providing greater control and flexibility in implementing colors in app designs.

In addition, Uno Platform has added a custom color feature that eliminates restrictions on the number of colors used in a design, enabling designers and developers to create colors that suit their specific requirements. This feature offers designers greater creative freedom to create unique and customized color schemes that enhance the overall design aesthetic.

This Preview 5 introduces three new controls, including the highly anticipated vertical-oriented TabBar. TabBar control provides developers and designers with the ability to toggle between horizontal and vertical navigation bars, making it especially valuable for designing tablet-format applications. With this feature, designers can offer improved usability by utilizing a vertical navigation bar that complements the larger screen size.

PipsPager is another new control in Preview 5. This dynamic and versatile element offers advanced functionality for creating interactive designs, allowing developers and designers to create paginated interfaces with rich features such as smooth transitions, animations, and gestures. With its customizable design, PipsPager is ideal for applications that require complex navigation and data manipulation.

Furthermore, Preview 5 introduces the ItemsRepeater control, a data-driven panel that offers a unique approach to displaying collections of items. The original release blog post delivers the following statement:

ItemsRepeater is not a complete control, but rather a flexible panel that provides a template-driven layout for displaying collections of data. It offers greater customization options, allowing designers to have full control over the visual appearance and behaviour of the repeated items, making it highly suitable for designing interfaces with complex data presentation requirements.

Preview 5 also brings two notable updates to its image preview and display features. The placeholder image has been refined to aid designers in creating more accurate visual representations of their designs, and the need to alter images to a random preview image generated by the plugin has been eliminated. Images will now appear in the plugin precisely as they are displayed in the Figma file.

The Uno Platform for Figma plugin is rapidly developing into a robust tool that facilitates the app development process for developers and designers. Its latest features empower users to take greater control of their design and development workflow, enabling them to quickly move from the design phase to development without encountering common obstacles. And lastly, in addition to the original release blog post, users can find the detailed YouTube video tutorial published by the Uno Platform team, the video provides step-by-step instructions on how to download and launch the plugin.

MMS • Matt Campbell

Amazon moved CodeCatalyst into full general availability with a number of new features. CodeCatalyst provides templates to streamline creating the project’s infrastructure, CI/CD pipelines, development environments, and issue management system. New features with the GA release include better support for GitHub repos, integration with Amazon CodeWhisperer, and support for AWS Graviton processors.

Released at re:Invent in 2022, CodeCatalyst is built on four foundational elements: blueprints, CI/CD automation, remote development environments, and issue management. Blueprints set up the application code repository, including a sample app, define the infrastructure, and run pre-defined CI/CD workflows.

With the GA release, there are now blueprints for static websites built with Hugo or Jekyll and intelligent document processing workflows. These join the already released blueprints that support building single-page applications, .NET serverless applications, and AWS Glue ETLs.

When a project is created from a blueprint, a full CI/CD pipeline is also provided. This pipeline can be modified with actions from the provided library. As well, any GitHub action can be used directly within a project either within an existing pipeline or to build a net-new pipeline. Editing the pipeline can be done either via a graphical drag-and-drop editor or by editing the YAML directly.

CodeCatalyst provides developer environments that are hosted within AWS. These environments are defined using the devfile standard providing a repeatable and consistent workspace. The devfile standard is an open standard for defining containerized developer environments. These environments can integrate with a number of IDEs such as AWS Cloud9, VS Code, and JetBrains IDEs.

Finally, CodeCatalyst projects provide built-in issue management tied to the code repository. This facilitates assigning code reviews and pull requests. Adding new teammates to a project does not require an AWS account per user. Instead, users can be added to an existing project via their email address.

Additional new features include support for creating new projects from existing GitHub repositories. Note that empty or archived repos can’t be used and the GitHub repositories extension isn’t compatible with GitHub Enterprise Server repos. The CodeCatalyst Dev Environments now also supports GitHub repositories. This supports cloning an existing branch of the linked GitHub repo into the Dev Environment.

CodeCatalyst Dev Environments also now support Amazon CodeWhisperer. Amazon CodeWhisperer is an AI-supported coding assistant that generates code suggestions within the IDE. At the time of release, only AWS Cloud9 and VisualStudio Code are supported. Amazon CodeWhisperer is similar to GitHub’s Copilot, which recently released a new AI model.

This release also adds support for running workflow actions on either on-demand or pre-provisioned AWS Graviton processors. According to Brad Bock, Senior Product Marketing Manager at AWS, and Brian Beach, Principal Tech Lead at AWS, “AWS Graviton Processors are designed by AWS to deliver the best price performance for your cloud workloads running in Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2)“.

As noted by Bock and Beach, CodeCatalyst is about reducing the cognitive load on developers:

Teams deliver better, more impactful outcomes to customers when they have more freedom to focus on their highest-value work and have to concern themselves less with activities that feel like roadblocks.

Cognitive load has been receiving more attention as developers have increased responsibilities to manage and maintain to deliver working software to production. Paula Kennedy, COO at Syntasso, echos this sentiment:

With the evolution of “DevOps” and the mantra “you build it, you run it”, we’ve seen a huge increase in cognitive load on the developers tasked with delivering customer-facing products and services.

Amazon CodeCatalyst can be used on the AWS Free Tier. More details about the release can be found on the AWS blog as well as within the documentation.

Meet the Undisputed King of Real-Time in Serverless Databases – Analytics India Magazine

MMS • RSS

|

Listen to this story |

If real-time use cases on serverless databases had a face it would be of Redis. “Obviously, we at Redis are convinced that SDBaaS Redis is ideal for real-time applications,” said Yiftach Shoolman, co-founder and CTO of Redis, in a blog post, sharing how the popular key-value database system was ahead in the game.

| SDBaaS is a cloud-based database service that allows developers to focus on building applications while operation works of running the applications are taken care of by the cloud provider. |

“The serverless database-as-a-service (SDBaaS) market opportunity is huge, and it is another reason why Redis Enterprise Cloud makes sense for any real-time use cases,” said Shoolman.

According to Shoolman, Redis Enterprise Cloud is easy to manage, flexible, scalable, and extremely cheap. The company believes that the cost of operation is much more meaningful than the cost of storing data, and each operation in Redis is cost-effective. “It ensures real-time experience for your end users, as any database operation can be executed in less than 1 msec,” he added.

In a previous interview with AIM, Schoolman spoke about the challenges with real-time applications. He said that from the time a request is put, nobody wants to wait for more than 0.1s i.e. 100ms, and that every delay in a database is reflected 100 times more to the end user. If a database is slow, the delay is even more aggravated for the end user.

“There’s always a misconception that Redis is expensive because it runs on memory but in the real time world, it is cheaper,” he said.

Redis vs DynamoDB

On the other hand, DynamoDB is a NoSQL database service provided by Amazon. To maintain a swift performance, DynamoDB spreads the data and traffic over a number of servers so as to handle the storage and throughput. The database can create tables capable of storing and retrieving any volume of information at any level of traffic.

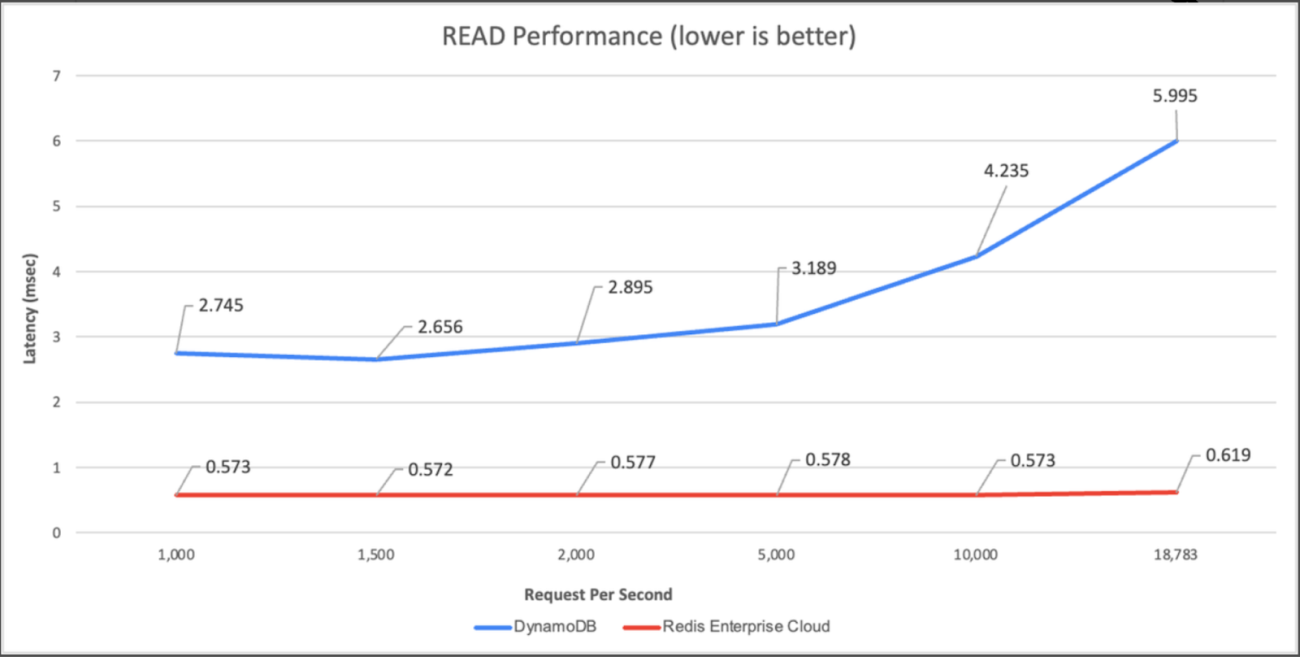

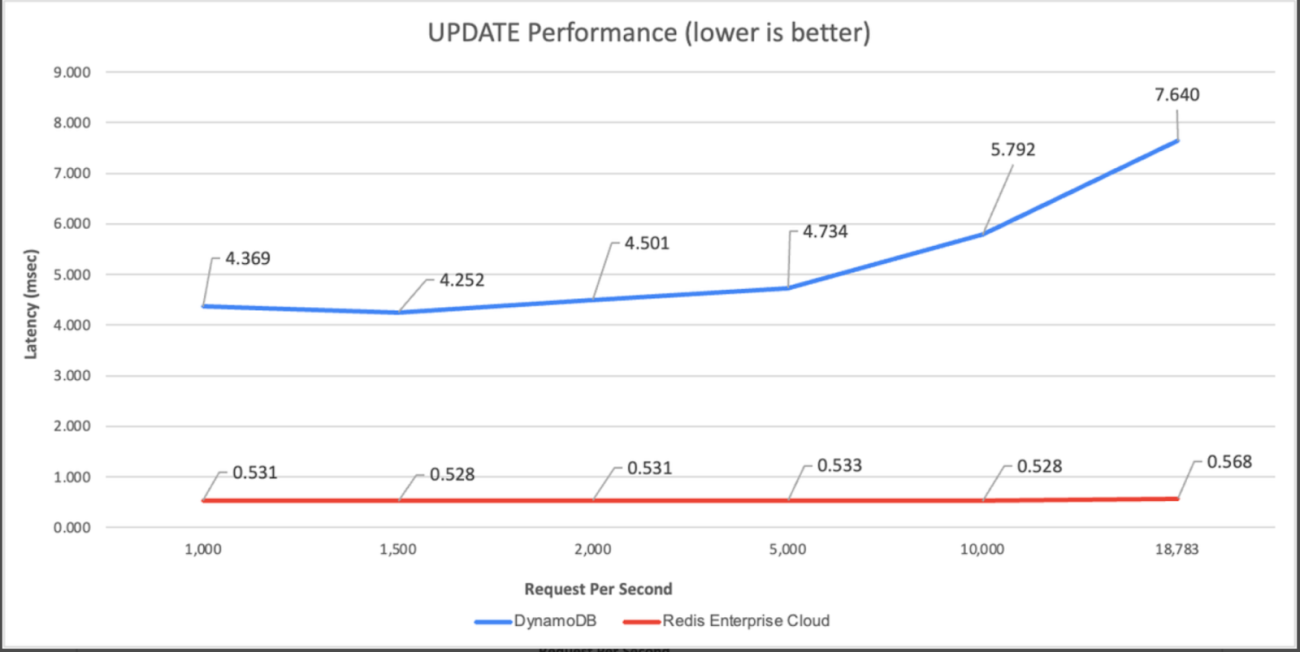

In comparison between the two, Redis comes out on top. At 1,000 requests per second, Redis Enterprise Cloud is 6.44 times faster and 15% cheaper than DynamoDB, and at 18,000 requests per second, the cost is at 2% of DynamoDB and 11 times faster.

On comparing Redis and DynamoDB on read (process of retrieving data from the database) and update (process of modifying existing data in the database) performance, by running common workloads with a 50GB fixed dataset, Redis maintained an end-to-end latency of 0.5-0.6 msec while Dynamodb performed no faster than 2.7ms (for read) and 4.4ms (for update).

Source: Redis blog

Redis Enterprise Cloud was built on a serverless architecture from the start, and allows developers to be billed for what they set. Redis enables a single core to manage a large number of operations when compared to other databases that use dozens or hundreds of cores. This results in making the database highly cost-effective. Redis relies on DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory) which is faster and more expensive than SSD (Solid State Drive), but the cost for the service is based on the number of operations and not how much data is stored.

Redis vs the World

In addition to DynamoDB, there are a few other SDBaaS platforms that have versatile uses, and probably comes close to Redis’ performance.

MongoDB

A serverless NoSQL database, data in MongoDB is stored in the form of a document. This makes it simpler for developers by providing a flexible schema. When it comes to performance, Redis is faster as it has an in-memory database. This means it is more suited for building intricate data structures, whereas MongoDB is ideal for medium-sized enterprises. However, Redis uses more RAM than MongoDB with large datasets.

CockroachDB

CockroachDB is a distributed, scalable, and generally available open-source relational database management system which is designed to support transactions across multiple nodes in a cluster. CockroachDB can handle large volumes of data and can be used for a wide range of applications. Simply put, the database is designed for scalability and fault tolerance whereas Redis prioritizes high performance and low latency.

With time, choosing an appropriate cloud database has become an increasingly complicated task. In order to enhance efficiency and cost-effectiveness, developers need to sort through a diverse range of instance types, determine the most suitable number of cores, and evaluate several pricing alternatives. Considering how each database is different from the other, it boils down to their functionalities and intended use. Going by the comparison benchmarks and Redis’ in-memory database that pushes for speedy performance, its superiority in the segment is clear.

MMS • Nsikan Essien

Momento now offers Momento Topics, a serverless event messaging system that supports publish-subscribe communication patterns. This service is designed to provide a messaging pipeline for event-driven architectures and subsequent feature releases will allow direct AWS Lambda invocations and change data capture events triggered from Momento Cache.

Momento aims to enable developers to quickly write reliable and powerful applications. Their first product, Momento Cache, launched in 2022, is a serverless cache for database and application use cases that has been described by serverless advocate Alex DeBrie as “a cache for the 21st century—for the serverless, cloud-enabled era.” Momento Topics is the second service from the Momento team and is designed to immediately deliver published messages to all current subscribers of a topic, after which they are discarded. Momento recommends this service for scenarios where low latency message delivery is prioritized over occasional message loss. As messages are not stored indefinitely on Momento Topics, usage is billed against volumes of data moved via the service.

The key benefits of Momento Topics include a simplified pricing model with a 50GB free tier, configuration-free management of topics, and millisecond tail latencies at high scale. To use Momento Topics, applications need to install the Momento SDK, which has varying levels of support across eight programming languages and frameworks, including Node.js, .NET, and Java. As Momento Topics is backed by Momento Cache, applications will need to connect to an existing cache instance via the SDK prior to publishing or subscribing. Below is a code snippet showing how to set up the client to publish in Node.js:

import {

TopicClient,

TopicPublish,

Configurations,

CredentialProvider,

} from '@gomomento/sdk';

const momento = new TopicClient({

configuration: Configurations.Laptop.v1(),

credentialProvider: CredentialProvider.fromEnvironmentVariable({

environmentVariableName: 'MOMENTO_AUTH_TOKEN',

}),

});

const publishResponse = await momento.publish(cacheName, topicName, value);

if (publishResponse instanceof TopicPublish.Success) {

console.log('Value published successfully!');

} else {

console.log(`Error publishing value: ${publishResponse.toString()}`);

}

To subscribe, the code is similar, with the addition that the client needs to register a callback that can be triggered when new items arrive:

const response = await momento.subscribe(cacheName, topicName, {

onItem: handleItem,

onError: handleError,

});

function handleItem(item: TopicItem) {

console.log('Item received from topic subscription; %s', item);

}

function handleError(error: TopicSubscribe.Error) {

console.log(`Error received from topic subscription; ${error.toString()}`);

}

The Momento team has also announced plans to enhance the subscription functionality of Momento Topics with two features. The first, Executors, would allow Lambda functions to be directly invoked as subscribers to topics, while the second, Triggers, would allow subscriptions to be triggered based on changes to data stored within Momento Cache.

Momento Topics is comparable to services like AWS Eventbridge, Azure Event Grid, and GCP Eventarc, as it focuses on decoupled application integration via events. While it offers a similar serverless and low configuration overhead to other services, it differs in regard to its dead-lettering/event delivery capabilities. Where the other services do not guarantee event delivery order and utilize dead-lettering, Momento Topics provides messages with sequence numbers and aims to enable initialization of subscriptions from a checkpointed sequence number. Another key difference with Momento Topics is the amount of publishers and subscribers it supports natively. While AWS Eventbridge, Azure Event Grid, and GCP Eventarc have integrations with their wider ecosystems, Momento Topics has only announced future integrations with AWS Lambda and Momento Cache.

Further information on how to get started with Momento Topics can be found on its documentation page.

MMS • Jim Barton

Transcript

Barton: We’re going to talk about sidecars, eBPF, and the future of service mesh technology. My name is Jim Barton. I am a field engineer with solo.io here in North America. Solo is a company that’s very passionate about application networking, especially in a cloud native context. We supported a number of the largest and most influential open source projects in that space, things like Istio and Envoy proxy, as well as other projects like GraphQL and Cilium.

Parsimony (The Law of Simplicity)

I wanted to set the stage for this presentation, I want to take you back to something that happened just a few months before my graduation from engineering school a long time ago. This story goes back to a competition that was held with my IEEE student chapter, actually multiple IEEE student chapters from around our region that got together and had a contest. It was a robot car racing contest. You had a car that was to trace a line very much like what you see here in the picture. The idea was to go as fast as possible, and to beat out all the other schools. This was a high energy competition that had a lot of entrants from a lot of different engineering schools, a lot of really interesting designs. Most of them were fairly complex, some of them were a little funny. At any rate, to boil it all down, there were two designs that worked their way through the single elimination competition. One of them was this huge behemoth of a design. It had this giant central core, and these rotating legs that came off that central core, each with their own wheels. The superstructure would rotate, and would propel this vehicle down the black path there. It came from a very large, very well-respected engineering school, had a big following with a big operations team. It was a pretty impressive thing to watch.

As the competition went on, this entrant went all the way to the finals. Then there was an underdog that went through to the finals as well. It was pretty much the polar opposite of our giant behemoth. It was a little tiny entrant from a small engineering school, they sent a single delegate to this convention. He built this thing, it looked like it used the chassis of a child slot car, and had a little tiny, sweeping photodetector at the head of the car with a little battery and a little motor to drive things. It just swished its way down the track and was beating all of these much bigger, much better funded competitors. We got to the end of the competition, and there were two finalists left standing, the big behemoth with the giant rotating legs and the D cell batteries hooked into the superstructure against the little tiny one designer slot car.

I learned a lot of things my senior year of college, but that particular day taught me a lesson that I have never forgotten. That is the lesson of parsimony. Parsimony, simply being the law of simplicity. When you have a design goal in engineering, and there are multiple paths to get there, all other things being equal, the simplest path, the fewest moving parts are generally the best. As we transition into discussing the future of service mesh, the way that I see the trends in the marketplace right now, it’s all about simplicity, recognizing that we need to move toward more simple designs of our service mesh technology. There have been some really exciting developments in that space, just within the past month or two. We’re going to talk to you about that as we go forward.

Before Service Mesh

To set up that discussion, let’s go back to the “beginning.” Let’s assume you’re living in prehistoric times, let’s say 2017, and you have services that need to communicate with each other. Before there was service mesh technology, you might have two services, service A and service B. Let’s say you are a financial institution or a government entity, or in some other industry like telco that’s heavily regulated. Maybe you have a requirement like, all communication between all services need to be encrypted and use mTLS technology. Let’s say that requirement was presented to you in these prehistoric times, how might you fulfill that? You’d go out, you’d Google TLS libraries for whatever language service I’m using. Maybe you’d integrate that, and you’d test it out with the service or services it needed to communicate with. You’d deploy it and everything would be fine.

That approach is fine as far as it goes. The problem is, there aren’t many of us sitting in on this session, who live in such a small-scale environment. We often live in environments that look something more like this. I spent a number of years at Amazon, and we actually had a chart that was on a lot of walls in a lot of places that we call the Death Star. The Death Star showed, at some snapshot in time, all of the various microservice interactions that were happening within the Amazon application network. The simple approach where each application dealt with its own security infrastructure, metrics production, advanced routing capabilities, that sort of thing. It really didn’t scale very well into an environment like this. It caused us to ask a number of questions about if we want to build microservice networks at scale, how can we best answer questions like this? How do we secure communication between services in a repeatable, reliable fashion? How do we manage things like timeouts and communication failures? How do we control and route our traffic? How can we publish consistent metrics? How can we observe interactions among all of these various services?

Service Mesh Separates Concerns

We began to realize collectively as a community that a lot of these concerns that we talk about here are actually cross-cutting. They apply to all of these services. Wouldn’t it be good rather than building this undifferentiated heavy lifting logic into each and every application, what if we could externalize that in some way and handle these cross-cutting concerns in some piece of infrastructure? The first architecture that came out of just about every service mesh platform in that era was through something called sidecar injection. You see that depicted here where there would be a sidecar injected that lived next to the application code in question, and would actually manage these kinds of connect, secure, observe concerns on behalf of the application. There you can see some of the very common capabilities that evolved or that were design goals for this first round of service mesh technology. The key pillars here being connect, secure, observe what’s going on inside your complex application network.

How Istio Works Today – Data Plane, Sidecar Proxies

Whether we’re talking about the Istio service mesh, or a variety of other service meshes that are out there, a lot of them operated along this same basic architectural line. That is, there are two components, there’s a data plane component and a control plane component. The data plane component is actually responsible for the processing of the request. What would happen is, at some point, an Envoy proxy would be injected into each one of those services as a sidecar, and the sidecar handling all of these cross-cutting, connect, secure, observe concerns. When an application needed to talk to another application, say service A needs to talk to service B, then those kinds of issues, metrics, publication, and failover, and timeout, could all be handled by these Envoy proxies that would intercept all of the requests going in and out of various service components. Let’s say you have a security mandate. You have a security mandate, and by simply injecting these sidecars into your applications and applying some very simple policies, then you could guarantee that your network of microservices was using proper security practices to manage traffic inside the mesh. That’s the data plane.

How Istio Works Today – Control Plane

The data plane also depends on a control plane. The control plane is the brains of the operation. There is some outside stimulus that comes in, maybe it’s a kubectl command, or it’s an Argo controller that’s applying configuration, something like that, that’s actually specifying what kinds of policies we want to apply within our service mesh network. The control plane then is responsible for taking those policy specifications, translating those into configuration for the various Envoy proxies deployed in all of the services around our network, and making sure that those Envoy configurations are distributed properly, out to the various services so that those policies can be enforced in the best and proper place. That’s been the general state of the service mesh technology for a while now.

Istio Sidecar Model Challenges

Let’s be clear, there are a lot of people who have been and who are very successful using this architectural approach, because it does solve a lot of problems. There are a lot of cross-cutting concerns that are able to be absorbed into the mesh components so that that work no longer has to be done in the application code itself, which is a very good thing. There are operational challenges that have arisen as we gained experience over the intervening, say, four years since Istio went 1.0 GA release in 2018. Over the intervening years, we’ve learned a lot. This is a great quote from a very senior engineer at T-Mobile named Joe Searcy, and what he said, the biggest enemy of service mesh adoption has always been complexity of the resource and operational overhead to manage the service mesh for a large enterprise, makes adoption cumbersome, even as projects like Istio have worked to decrease complexity. We’re talking here about this particular approach. While it does remove a lot of cross-cutting concerns from the underlying application, it can be fairly complex to administer, especially at scale.

Let’s talk about briefly just a couple of those issues. Then we’ll talk about some of the innovations that are going on right now to address that, from an operational complexity standpoint. This shows you a typical Istio deployment, obviously simplified quite a bit. You can see we have three nodes that are deployed presumably in our Kubernetes cluster. There are a number of apps that are deployed, some of them with multiple instances. Because we’re using Istio, we have an Envoy proxy sidecar that’s injected into each one of those application pods. There are issues that can happen, let’s say, because these components, the application workload and the proxy, live in the same pod, there can be issues when you’re trying to take down a service, maybe to apply an update to the underlying workload software, maybe to apply an update to Envoy itself, or to the Istio data plane. There can be issues like, for example, let’s say the application comes up first, app 1, and the sidecar, there’s a race condition there. The sidecar hasn’t quite made it yet. The application starts to try to do its thing to fulfill its mission. It sends out requests, but there’s no sidecar to intercept that request and apply whatever policies are relevant. As a result, it may spew a number of failures as it’s in this race condition, startup phase. That’s not a good thing.

There’s converse sorts of problems that can happen when services are trying to shut down, and so forth. This race condition, that’s an artifact of the fact that we’ve injected this proxy into the pod. It’s something that we’d like to avoid if possible. Although our goal is for applications to not be aware of the mesh, in fact, sometimes it does need to happen. For example, here’s a case where we have a pod that spins up a job, and so this is a job that’s going to run for some period of time. It completes its mission, and then it shuts down. We have operational issues like when that job shuts down, you can have conditions where perhaps because the sidecar is still running, that pod is not cleaned up properly. Those resources are not cleaned up in a proper timely fashion, in order to use those resources as efficiently as possible. That’s something we’d like to address as well.

There’s also a very popular topic of latency. What happens here with our sidecars is those are injected into the application workload. Those sidecars have, obviously certain latency that’s associated with them. These are fully configured Envoy proxies that live as sidecars in Istio. They have a full layer 7 TCP stack that has to be traversed, every time traffic goes in or out. You can see, you get some latencies that build up going from the application to its sidecar into another sidecar. Then to the serving application, that can be a few milliseconds of processing time. That’s something we’d like to improve as well.

Then, finally, from a cost standpoint, all of these Envoy sidecars that we are provisioning, they cost money, they cost memory, and CPU, and actual money. One of the things that we see in our business as we talk to people is that often, because you don’t want these sidecars to be under-provisioned, because that creates issues. What happens is often people tend to overprovision the sidecars, give them more capacity than they need. That actually results in an unnecessary spending of money, which is something we would like to avoid as well. Those are some of the challenges.

Introducing Istio Ambient Mesh

Again, this model has worked very well for a number of years, but there are some challenges and we’d like to be able to address that. The folks at Google and Solo have been talking about this problem for roughly a year, maybe a little longer now, and have just contributed in the September timeframe to the Istio project, a new sidecarless data plane option that allows service meshes to operate completely, if that’s what you want, without sidecars. That has a number of really important implications that we’ll be talking about. Things like cost reduction, and simplifying operations, and improving performance. We will talk about all of those.

Including Applications in Ambient

One of the things from an operational standpoint that you see is it’s much easier to get started with Istio Ambient Mesh due to the simplified onboarding process. When you were working in a sidecar mode, obviously, every workload in a namespace that you wanted to include into the mesh, you have to go inject sidecars into each one of those. It’s a decently heavyweight process. Whereas with ambient mode, it’s simply a matter of labeling your namespace as being, I want this namespace to be something that participates in the mesh using ambient mode. What happens is the appropriate infrastructure will get spun up to make that a reality, but without any change to the underlying workload itself. You’ll see that in the demonstration in just a few minutes. Similarly, if you want to take things out of the mesh, it’s a very simple process, where you’re just simply taking away that infrastructure, the Istio CNI will change some routing rules. Basically, the underlying workload itself remains completely untouched. Pretty good stuff.

Ambient Architecture

How this works, is there are two layers to the Istio ambient mode, two new layers that you can use. These modes can interoperate with each other as well. If you have existing workloads that operate in a sidecar fashion, and you want to spin up, let’s say, new services that operate in ambient mode, those two can interact with each other. There are no issues there at all. Going forward, we anticipate a lot of the new adoption in Istio once ambient is really, fully production ready. We see a lot of new adoption going in this direction. Ambient mode is available in Istio 1.15 on an experimental, basically on a beta basis. It’s not considered ready for production use yet, but we are moving up the experience curve very quickly and expect it to be a predominant deployment model going forward. When we add ambient mode to a namespace, what we actually get are potentially two different sets of components. There is a secure transport layer that operates on a per node basis, it handles just level 4 issues. Its primary purpose is to manage securing traffic between workloads. We’ll show you a picture of that in just a moment.

Then, in cases where you also need layer 7 policies, things that require HTTP headers, maybe retries and fault injection, and advanced load balancing, those sorts of things that require layer 7 HTTP access, those policies will be delegated off to a separate set of layer 7 proxies that we’re calling waypoint proxies. Two layers here, one is ztunnel that handles primarily level 4 security mTLS kinds of concerns. Then a second waypoint proxy layer that operates at layer 7 and handles the higher-level set of concerns typically associated with HTTP. In terms of the control plane architecture, as you can see there at the bottom, that’s unchanged. Same APIs as before. The control plane is the same old istiod control plane that you may have used if you’ve used Istio in the past. It will program the ztunnels and the waypoint proxies exactly the way it’s always programmed sidecars, and will continue to program sidecars in the future. Those are the two layers of the ambient architecture.

What you see with a request, so let’s say we just care about establishing mTLS through our network, and that’s a common adoption pattern that we see for Istio. People often don’t want to bite off on the full connect, secure, observe, all the features of Istio initially. A lot of times they come to us with a mandate, like for example, federal agencies, public sector clients come to us with a mandate, say from the Biden administration that we have to use mTLS security among all the applications in our mesh. We do that here with this ztunnel component. What’s going to happen is, if app A wants to talk to app B, the request goes to the ztunnel. The ztunnel then directs that to the ztunnel, where the target application is, manage this communication, the request and the response back and forth between the two, and life is good.

It’s very possible then to do this incremental adoption of Istio using ambient mesh, where if all you care about is mTLS, you can get by with just these very simple per node deployments that are not injected as sidecars into your applications. If layer 7 policies are needed, and they often are, then we’re going to introduce the notion of a waypoint proxy where you can provision these proxies as you want. They don’t have to be on any particular node. You can provision using standard Istio service deployments. They’re going to handle all of the layer 7 kinds of policies that need to be applied to a particular request. You don’t have to worry about the details of how these proxies get programmed, istiod control plane is going to take care of that for you. You simply specify via the API, what you want done, and the control plane is going to make sure that the proper components are programmed as they need to be. Those are the two layers.

Why Istio Ambient Mesh?

From a benefit standpoint, we see right off, reduced cost. That one’s a pretty obvious one. Instead of having, in this case, we got 12 workloads across 3 nodes, each with their own layer 7 proxy, we can now eliminate those proxies in favor of an approach that uses, again, if we’re doing just security, we can do a proxy per node as opposed to a sidecar proxy per pod, so really reduces the set of infrastructure that is required there. In doing that, we see some pretty dramatic cost reductions. You can actually go visit this blog, if you’d like to explore this in more detail, bit.ly/ambient-cost, will take you there. Just to give you the conclusions of this, comparing the sidecar approach to the ambient approach, especially for cases where you’re doing incremental adoption of just the security features of Istio, you can see pretty dramatic, in some cases, like 75% reduction of the amount of CPU and memory required to accomplish the same objective. Going back to our original theme of simplicity, we’re trying to make this new model as simple as possible.

Another thing, and this is perhaps the most significant benefit of the ambient architecture, from what people are telling us is the potential for simplifying applications. We’ve talked about some of the issues around upgrades, and around adding new applications or taking things out of the mesh, this becomes a much easier process now. If we’re doing a rolling upgrade, say there’s an Envoy CVE at layer 7, and we need to roll that out throughout our service mesh network, we don’t have to go take down every single workload that’s in the mesh, in order to make that happen, we can simply do an update at the proxy layer. Immediately those changes will be visible to the entire mesh without the actual applications being impacted. That is a huge benefit here. We can see this graphically here where this is our initial pre-ambient setup. If we just need the security components, we could go to something like this where we have, rather than one sidecar per proxy, we have one per node where workloads are deployed. Those are not injected as sidecars. They are their own standalone ztunnel deployments. Then if we need more sophisticated layer 7 processing, we can add that as well as a separate set of deployments. We can scale those up independently of one another based on how much traffic we anticipate to be going to the service account in question.

From a performance standpoint, just a very simple analysis here that I think nevertheless illustrates what’s going on. We have these ztunnel proxies that are configured with Envoy and layer 4. Because they’re just dealing with the bottom level of the TCP stack, they’re much more efficient than if you have to go through the full layer 7 stack. We anticipate the proxy overhead of these layer 4 proxies, about a half millisecond back of the envelope on average. Layer 7, so the waypoint proxy is typically 2 milliseconds of latency added. You can see no mesh is obviously the baseline case, there’s no proxy overhead there. In the traditional model with L4 plus L7, and you’re guaranteed to have to traverse two of these proxies on each request-response, that’s about 4 milliseconds of added latency. Whereas if you’re just doing layer 4, again, secure communication, that can be as low as 1 millisecond of overhead, or with the full layer 7 policies taken into account, even there, there’s typically a significant reduction, say from 4 to 3 milliseconds. We think this is something especially applied at scale where people are going to see pretty dramatic differences in performance cost and operational overhead.

Ambient Mesh Demo

We’re going to switch over at this point and show you a demo of ambient mesh in action. We’re going to start by installing Istio. If you come here and look at our cluster, we don’t have Istio system installed. We have a handful of applications, some very simple sample applications that we’ll use to demonstrate this capability. The sleep service here, if we exec into this, we can curl helloworld, and get a response from one of the services. In this case, I see it load balancing between v1 and v2. I can even curl a specific version if I want. I can curl the other version as well. What we want to do is we want to install Istio. We want to implement service mesh capabilities without having to deploy a sidecar. Let’s come over here, and we will run Istio install. We’ll run it using istioctl. We will set the profile to ambient mode. Let’s take a moment. We’ll install some familiar components like the istiod control plane. It installs ingress gateways as well. Then we’ll come to some of the new components like the ztunnel that we’ve been talking about. If I come back here, and we look to the bottom pane, we see that Istio system has been installed as a namespace. If I click into that namespace, we see some components that run as a CNI plugin on the node. We see the istiod control plane, and we see the ztunnel agents that are deployed in a daemon set, one per node.

The next thing we’re going to do is we’re going to add our applications in the default namespace to this ambient mesh. What we’re going to do is label the default namespace with ambient mode, or data point mode, which is equivalent to ambient. Now we’ll automatically add the workloads that are in the default namespace, these services are going to go into the ambient mesh. If you notice, there are no sidecars. In fact, these applications have been running for a while, so we didn’t have to restart them or inject anything into them. We didn’t have to change their descriptors or anything. If we come in to the sleep application, which we see is running on the ambient worker node, and we exec into that, and we come back down here to this pane, we find that the ztunnel that’s running on the ambient worker node, and let’s say we watch its logs. Let’s do that full screen. If we now do our curl to helloworld, then what we should see is traffic that’s now going through the ztunnel. If you look a little bit closer at the logs, we can see things like while it’s trying to do some mutual TLS, or it’s invoking SPIFFE and establishing mutual TLS. Let’s take a closer look when we make those calls through the ztunnel. What does that actually look like? We’re going to do a kubectl debug in the Istio system namespace around the ztunnel, and we will use netshoot to help us understand what’s going on here. Let’s take a look at this.

Let’s come back here, and let’s make a couple of curls actually just to capture some traffic between sleep and helloworld. We’ll stop now, we probably have enough traffic. Let’s come back a little further up here. We should see that when the traffic is going through, like here we see traffic getting to the ztunnel. Then when it gets there, we have TLS encryption. The traffic going over the ztunnels, we get mutual TLS between the sleep and the helloworld service. As a reminder, we didn’t inject any sidecars into these workloads. We didn’t have to restart those workloads. All we’ve done in ambient mode is we’ve been able to include those workloads and the communication between them as part of the service mesh. A big part of the service mesh is also enabling layer 7 capabilities. That’s where the waypoint proxy or the layer 7 capabilities of the ambient mesh comes into the picture. Instead of the traffic passing between these tunnels, we can actually pass them and hand them off to a layer 7 Envoy proxy, which then implements certain capabilities like retries, fault injection, header-based manipulations, and so forth.

In this demo, we’re going to deploy a waypoint proxy, and we’re going to inject a layer 7 policy fault injection. In this case, we’ll observe how we can implement layer 7 capabilities in the service mesh in ambient mode without sidecars. To do this, let’s get out of termshark. Now we’re going to apply a waypoint proxy. Let’s take a look at that, the layer 7 proxy for the helloworld services. One thing you’ll notice is we don’t try to share layer 7 components between different identities, we want to keep those separate and try and avoid noisy neighbor problems. We can create this waypoint proxy by applying this. Then we should see a new proxy come up, that would enable us to write layer 7 policies about traffic going into the helloworld service.

Now, if I come back, we can take a look at a virtual service, which is a familiar API in Istio that specifies traffic rules, when a client tries to talk to helloworld, and in this case, we’ll do some layer 7 matching, and then we’ll do some fault injection. A hundred percent of the time, we will delay the calls by 5 seconds. Let’s apply this virtual service, and then we’ll go back to our client. Now when we curl the helloworld service, we should see a delay of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 seconds. We should see that potentially load balance across both v1 and v2. As you can see, we get layer 7 capabilities, we get layer 4 capabilities and mutual TLS. We can write policies about this communication between these services, and we have not touched the applications. We can include them and even exclude them dynamically. If we’re done with this service, and we don’t want it anymore, then all we have to do is just uninstall it. Then we’ll remove the system namespace and come back to our applications. You see that they’re not touched. Go into one of the applications, we make a curl. Then without ambient in place, the services continue to work, just as we expected.

Summarizing Istio Ambient Mesh

To summarize what we’ve seen so far with Istio Ambient Mesh, both from a presentation and a demonstration standpoint, three core benefits remain. We want to reduce cost. We want to perhaps, most importantly, simplify operations. We want to make the service mesh truly transparent to applications. Decouple the proxy from the applications and just make it part of the core infrastructure, and so simplifying doing things like application updates. We want to improve performance as well by taking advantage of this new proxy configuration that allows us to just bite off on the functionality that we need for our particular use cases.

Responses to Istio Ambient

What are the responses that we’ve seen to ambient mesh so far? I think the general responses have been very positive. Occasionally, there’s been a wait and see. Yes, this is interesting, but let’s see an introduction before we get too excited. This is one that I think is really interesting. This is from Matt Klein. Matt Klein is at Lyft, and was the founder of Envoy proxy built back in the mid-2010s. He says, “This is the right path forward. Sidecars have been an unfortunate implementation detail in the past. Now we’re going to see mesh features that get absorbed into the underlying infrastructure, excited to see how this evolves.” Going back to our quote from the beginning of this talk from Joe Searcy at T-Mobile. He says the opportunities that ambient Mesh provides are extremely exciting, better transparency for applications, fewer moving parts, simpler invocation, huge potential in savings of compute resources and engineering hours. Those are all really good things.

There’s at least one episode of unintentional humor. This is from the CEO of a company that leads the Linkerd community which has doubled down on its sidecar-based architecture. He actually put out a joke tweet in response to all of the chatter around ambient mesh, and said, “By the way, Linkerd, we’re actually going to switch to having a sidecarless option as well,” put some things in there to try to provide hints that he was joking. You can see a day or two later, he realized people weren’t getting the joke, so he had to come back and say, “Yes, this is a joke. We really like sidecars with Linkerd.” That was some fun that came out of this whole announcement process.

What’s Next in Service Mesh?

What’s next beyond this in service mesh? There are two capabilities. I want to talk about both of them on the data plane. That’s where we see a lot of the innovation happening these days, is in the data plane itself. One of the things we want to be able to do is to improve the performance of these new components. What we did for the experimental implementation that’s out there now is with the ztunnels. Those are implemented as Envoy proxies that are just configured to operate at level 4. There are some additional opportunities for increasing performance of that even more. What we see is being able to perhaps replace the Envoy proxy there with an even lighter-weight ztunnel implementation, even using technologies like eBPF. eBPF allows us to do things like packet filtering in the kernel of the operating system, and so it’s extremely efficient. It’s not something that’ll be a revolution in terms of what’s going on here. The architecture is going to remain the same, but just providing a more efficient implementation based on eBPF to actually make those ztunnels run even faster than they do today.

One other thing I want to talk about here is a different level of innovation. We’ve talked a lot about the architecture of the data path. I also want to talk about, there’s a lot of innovation happening with service mesh at the edge of the mesh as well. One really good example of that, that I’m excited about is GraphQL innovation. Just very quickly, with GraphQL, today, what we typically see in enterprises who deploy it is you have an architecture that looks roughly like what’s on the right here. You have an API gateway, something that’s like you’ve been using before that serves up your REST interfaces in your maybe gRPC, whatever APIs you have out there. Then you end up having to build this separate server component that knows just about GraphQL, how to assemble GraphQL responses from underlying services and that sort of thing. We’re not sure that’s the best approach. What if you could have GraphQL APIs that don’t require dedicated servers? What if you could reuse existing API gateways to serve GraphQL? It’s like they already serve OpenAPI, gRPC, other kinds of interfaces, why can’t they serve GraphQL as well? Why do we need to stand up a separate server component or set of server components in order to enable GraphQL? That doesn’t make a lot of sense. What if you could do that in a way that would allow things like declarative configuration, as well as leveraging your existing API contracts?

Solo has done a lot of work in this space, specifically in a service mesh context. Basically, the takeaway from the story is, what if you could actually absorb the GraphQL server capability into a filter in your Envoy proxy at the edge of your network? Basically, inspect existing applications and their interface contracts, derive GraphQL schema from that, be able to stitch those together to create a super graph that spans multiple services, and deploy those in an API gateway. We think that’s a powerful innovation growing in popularity API standard in GraphQL.

Resources

If you would like to learn more about any of the things we’ve talked about, especially ambient mesh, I definitely recommend this resource. There’s a Bitly link that will take you there, bit.ly/ambient-book. This a completely free book from O’Reilly, written by a couple of people at Solo, and basically goes through in a fair amount of detail, Istio Ambient Mesh, and will help you understand exactly what the objectives and implementations are there. There’s also a hands-on workshop, if you’re like me, and you like to get your hands on the keyboard to understand this stuff better. Encourage you to follow that Bitly link there, bit.ly/ambient-workshop. It will take you through a hands-on exercise for getting started with ambient mesh.

Did Parsimony Win the Day?

Back to our original story. What happened? We got to the finals. We had the big behemoth design with the committee and so forth, and the little tiny car with the single designer. Who won the day? The behemoth designers, they got in there at the starting line, two people carry it up to the starting gate, they twist up all the potentiometers to make it run as fast as possible. They spun it up a little too much, and the thing actually goes careening off the track. The little car just shuffles its way around the track, and it wins the day, much to the delight of all the college students who were there watching the finals of this competition. In my view, there was a happy ending, David beat Goliath. Parsimony and simplicity won the day. That’s what we think is going to happen in the service mesh community as well is that simplicity and ambient mesh are going to be ruling the day very soon.

Questions and Answers

Betts: You mentioned that the three pillars were secure, connect, and observe. The ambient mesh really seemed to focus on reducing the complexity and it helps for those connections. Then security doesn’t have to be configured as many places. Does it help with the observability as well?

Barton: Yes, absolutely. I’m not sure that ambient per se really addresses so much the observability concerns. There’s a ton of metrics that already get published out of Istio and Envoy proxy. If you’ve ever done anything with Envoy proxy, whether in a service mesh context or not, you’ll know that there’s just a raft of metrics that gets published there. I don’t think ambient really is going to enhance the observability per se, but it does just allow that to be delivered in a more cost-efficient fashion.

Betts: Do you see any service mesh deployments that aren’t using Kubernetes?

Barton: Obviously, no one, at the scale that I expect the people on this session are managing, you’re not dealing with Greenfields. Definitely, Istio has a lot of best practices established around non-service mesh deployments. We blog about it quite a bit at Solo, because these are the kinds of real-world issues that we encounter. I would not recommend trying to deploy Istio without any Kubernetes context at all. In other words, if Kubernetes is not part of the strategic direction of your organization, then I wouldn’t recommend going there. Definitely, if you’re in a mode, like a lot of the organizations we deal with where this is our objective is to move toward Kubernetes, and cloud native, and Istio service mesh deployments, then definitely can accommodate services that are deployed in VMs, or EC2s, or wherever.

Betts: If you’re doing the migration from a monolith architecture, and breaking it up into microservices, this is pricing that you’re thinking about, should it be one of the very first things you do, or should you figure out and learn Kubernetes first, and then layer on the Istio?

Barton: Anytime you’re contemplating a major organizational change, and this is independent of Kubernetes, or service mesh, start small, ideally. Start with something where you can wrap your mind around it and understand it, and that’s non-critical, and that you can manage the situation. Then, over time, layer in additional complexity and outside elements and that sort of thing. Just as a general rule, I think that’s a good idea.

Betts: eBPF, the Extended Berkeley Packet Filters, like even saying the acronym seems hard to me. It seems like one of those really low-level things that somebody’s really excited about, but me as an application developer, an architect, I don’t want to have to learn that. Is that something that you see eventually becoming something that’s sold as a package. Like, just get this add-in and it adds eBPF. It’s the thing that you had before, but now it’s lower level so it’s faster.

Barton: I think you hit it exactly right. It’s like I drive a car, I know very little about the internals, how an internal combustion engine operates. It’s something that just exists below the level of abstraction I care about. For the majority of people who are consumers of service mesh technology, I’d say the same would be true of eBPF. It provides a critical service. It’s going to make things run faster. It’s going to be below the level that most people are consciously dealing with. There are exceptions. In fact, if you go to academy.solo.io, you’ll see courses on eBPF, so you can learn more about it. There are people who clearly need to be able to understand it. Generally speaking, we think that will be commoditized, just baked into the service mesh layers. I know that Istio is clearly moving in that direction. I think some of the other alternatives that are out there, I know Kuma is moving in that direction, and probably some others as well.

Betts: Istio seems to be synchronous in terms of communication, does that come with scaling concerns? For async, can consumers control the rate of request consumption? Is that possible out of the box? Does he even have it in the right context, it’s about messaging and queuing solution?

Barton: You can definitely use Istio with asynchronous sorts of models. There’s no question about that. I view those two independently. I’ve done a lot of work building enterprise systems over the years and frequently will move into an asynchronous mode for applications that require extreme degrees of scalability and where the use case fits that. Definitely, Istio can be used in context of both synchronous and asynchronous services. The whole idea with Istio and with any service mesh, is to be as transparent as possible to the underlying applications. In the ideal world, it’s like an official at a sporting event. Ideally, I want to be there to enjoy the sporting event. I don’t want to watch guys in striped shirts blow whistles. That’s not my goal.

Betts: It should get out of the way, and like you said, a good abstraction. You don’t have to know about the details of how it’s doing it, but it shouldn’t also raise up to the level of your application has to know about all the Istio plumbing that’s there to be properly implemented.

You started to tease at the end, there’s future of GraphQL changes. Where’s that in the pipeline? Is that in the works, is it a year out?

Barton: No, definitely not a year out. I can speak with some authority to what Solo is doing in that space. Solo has a couple of products in this space. One is a standalone application gateway, it integrates with Istio, but does not require Istio. In that environment, there’s a full GraphQL solution that’s already there that basically allows you to absorb GraphQL server capabilities up into the Envoy proxy. There’s essentially a beta version of that that’s available in Solo’s commercial service mesh product that’s based on Istio as well that’ll be full implementation within a couple of months. Yes, it’s really exciting stuff. We see massive migrations of people toward GraphQL as an API standard, and we think a lot of the architectural decisions that are coming along with that are a little unfortunate. They don’t make a lot of sense to me. Why would we want a separate [inaudible 00:54:03] kind type of API server instance to serve up this API, when we already have something that serves up like REST, and OpenAPI, and gRPC, and so forth. Why can’t we bring those all together?

See more presentations with transcripts

MMS • Charity Majors

Transcript

Majors: My name is Charity Majors. I’m the co-founder and CTO of honeycomb.io, co-author of “Database Reliability Engineering,” and the newly available “Observability Engineering” book, which I wrote with Liz Fong-Jones and George Miranda.

Traditional Paths to Management

We’re going to be talking about the engineer manager pendulum. It started with a blog post that I wrote way back in 2017. For those of us who have been around for a while, there are traditionally two paths to management. One is the tech lead, the “best engineer” on the team, who then gets tapped to be a manager, and low-key resents it, but does it, and the career manager who becomes a manager at some point in their career, and takes that path and just sticks with it. They stop writing code. They stop doing technical work. Over time, this leads to decreased employability, and it leads to a lot of anxiety on the part of the manager who knows that they’re a little bit trapped in that role. It can seem a little threatening when you’re working with more technical managers.

Assumptions About Management

There are a lot of assumptions that we tend to have about management just by default. That it’s a one-way trip. That management is a promotion. That you make more money. That this is the best way to have and wield influence. That once you start managing, you want to climb the ladder. That this is really the only chance you get for career progression. That the best engineers make the best managers. This is all crap. These are all flawed, if not problematic. It results in a lot of managers who don’t really want to be managing or who become managers for the wrong reasons. I believe that your team deserves a manager who actually wants to be managing people, who actually wants to develop that skill set, not just someone who is resentfully filling in because they’re the only person or because they got tapped.

What The Team and Manager Deserve

The team deserves a manager who isn’t bitter about having to go to meetings instead of writing code. The team deserves a manager who has actual interest in sociotechnical processes, systems, and nurturing people in their careers. Lastly, and I think most controversially, I think the engineering teams deserve a manager whose technical skills are fresh enough and strong enough that the manager can independently evaluate their work, guide their development, and resolve technical conflicts. There are lots of teams where it doesn’t work this way. There are lots of teams where you’ve got a manager and a tech lead. The manager just relies on the tech lead to tell them if something is good or bad, or to develop the people. I’m not saying this can and doesn’t work. It does and it can. I feel like it’s a much weaker position to be in for the manager. I feel like it’s a compromise that whenever you’re having to outsource a major slice of your judgment to someone else and you can’t independently evaluate that, it’s not great.

You as a manager/tech lead/senior contributor in tech, you also deserve some things. No matter whether you’re an IC or a manager, you deserve to have career advancement. You deserve a role that is not a trap. You deserve something that you find interesting and compelling. You deserve to have the ability to keep your technical skills up to date and relevant, even if you’re a manager or a director, even if you’re a VP. I think that you deserve to preserve optionality. Especially if you aren’t sure what you want to do, you have a 30 or 40-year long career. Who actually knows what they’re going to want to do when they’re 50 years old? I think that you deserve to have the information that you need in order to preserve as many options as possible for the future. Relatedly, you deserve to have a long and interesting career where you can make choices that help you become more employable, not less.

I think that instead of just identifying as a manager or an engineer, as you progress in your career, I think it’s better to just think of yourself as a technologist, or as a technical leader, someone who needs those skill sets in order to really reach your fullest potential. It’s certainly true that there’s an immense depth and breadth of experience that accrues to people who go back and forth. In fact, the greatest technical leaders that I’ve ever worked with have all done both roles and had both skill sets. This used to be a pretty radical idea. In 2017, when I wrote this post, there was a lot of, whoa. Now, it’s not that radical. It’s pretty much common wisdom. This is great. It doesn’t mean that the journey is done. I’ve put some links there. I also wrote some follow-up posts about climbing the ladder, about management isn’t a promotion, why is that great.

I’m going to run through the material from the blog post. I’m going to spend more time on stuff about like, how to do this, if you’re an engineer or a manager. How to go back and forth. Why you should go back and forth. When not to go back and forth? Most importantly, as someone who has influence in an organization, how do you institutionalize this? How do you make this a career path inside your company so that it’s not just like the burnouts and the outliers and the people who are comfortable forging a new path, or who have nothing left to lose? Rather, how this is something that we include as an opportunity and an option when we’re coaching people in their career development. How do we make this bond?

The Best Line Managers, Staff-Plus Engineers, and Tech Leads

The best line managers, I think are never more than a few years away from doing hands-on work themselves. There’s no substitute for the credibility that you develop, by demonstrating that you have hands-on ability, and more importantly, that you have good judgment. You should never really become a manager until you’ve done what you want to do with senior engineering. Till you’ve accomplished what you want to accomplish. Until you feel solid and secure in your technical skills as an engineer because those skills are only going to decay when you become a manager. Keeping those skills relatively fresh gives you unimpeachable credibility, helps you empathize with your team. It gives you a good gut feeling for where their actual pain is. It keeps you maximally employable, preserves your options. You can’t really debug sociotechnical systems, or tune them, or improve processes, or resolve conflicts unless you have those skill sets.

Conversely, I think that the best staff engineers, staff-plus engineers, and tech leads tend to be people who have spent time as a manager, doing full time people management. There’s no substitute for management when it comes to really connecting business problems to technical outcomes. Understanding what motivates people. Most of what you do as a senior contributor, whether you’re an engineer or a manager, you don’t accomplish it through authoritarianism, or from telling people what to do. You do it by influencing people. You do it by painting a picture of the future that they want to join, and they want to contribute to, and they want to own. Even basic things like running a good meeting. This is a skill set that you develop as a manager that can really supercharge your career. You don’t have to choose one or the other, fortunately. You can do either. You can do both. You shouldn’t just pick a lane and stay there. However, you do have to choose one at a time. This is because there are certain characteristics of both roles that are opposing and not reconcilable. Lots of people are good at both of these things, but they’re good at it serially. They’re not good at it simultaneously. Nobody can do both of these things at once and do a good job of them because both people and code require the same thing, sustained, focused attention. Being a good engineer involves blocking out interruptions so you can focus and learn and solve problems. Being a good manager involves being interrupted all the time. You can’t really reconcile these in a single role. You can only grow in one of these areas at a time.

If you aren’t already an extremely experienced engineer, don’t go and become a manager. I know lots of people who have gotten tapped for management after two or three years as an engineer. It’s almost never the right choice. This tends to happen, especially to women, because women have people skills. It also can come from this very well-meaning place of wanting to promote women and wanting to put women into leadership and to management. It’s not a fast track to success. It isn’t. It derails your career as an engineer. It makes it much harder to go back from management to engineering. I don’t recommend people to turn to management until they have seven, eight years as an engineer. This is an apprenticeship industry. It really takes almost a decade to go from having the basics of a degree, some algorithms and data structures, to really having a craft that you’ve mastered. That you can then step away from, and be able to come back to it. There’s a myth around the best engineers make the best managers, though, and that’s just not true. You do not have to be the best engineer in order to be a good manager. There is no positive correlation that I have ever detected between the best engineers and the best managers. You do need to experience confidence and good judgment, and you need to have enough experience that your skills won’t atrophy. I think of it a lot like speaking a language. You learn a language best through immersion. If you step away, if you leave the country, or you stop speaking it every day, you get rusty. You stop thinking in that language. Just like when you stop writing code every day, your ability to write that code goes down more quickly than you expect.

If you do decide to try management, I think that you should commit to it to your experiment. Management is not a promotion, it’s a change of career. When you switch from writing code to managing, all of your instincts about whether or not you’re doing a good job or not, you can no longer trust them. It takes a solid two years, I think, just to learn enough about the job to be able to start to trust your gut, and to be able to start to follow your own instincts. I think that when you try and manage the first time, so more than 2 years, but less than 5. After a couple 2, 3 years, your skills do begin to significantly decay, especially the first time. Swinging back is a skill in and of itself. I think that after the first time, the requirements loosen a bit. After the second time, even more so. After a while, you will get good at going back and forth between the roles. Obviously, the more that you can keep your skills sharp while you’re managing, the more you can keep your hands warm, the more that you can continue to do some technical work even outside the critical path, the better. You will become unhireable more quickly than you will become unable to do the other skill set. People tend to be pretty conservative when hiring for a role that you’re not currently performing. Your best opportunity to go back and forth usually happens internally in the job where people already know you and trust you. It’s a lot harder to be an engineer and get hired as a manager. It’s not unthinkable, happens all the time. It’s harder, and there’s a higher bar, if you’re a manager and want to get hired as an engineer or vice versa.

Management Skills

Like I just said, technical skills are a lot like speaking a language. Speak it every day to keep sharp. Interesting management is not like that. Once you have your management skills, they don’t tend to decay in the same way. They tend to stick with you. That said, technical skills are portable. Yes, you need to learn about the local systems. You get better and more efficient and effective at a code base once you know it. Management skills, people skills are a lot more portable. You can take them from place to place with you and you don’t really have to start at the same low level and work your way up. You tend to bring them with you. You don’t need as much intimate knowledge of context. When you become a manager, you’re going to hear a lot of people tell you, stop writing code, stop doing technical work. I understand why people give this advice. It’s coming from a very good place. It’s coming from a well-intentioned place. Because most team managers, when they become a manager, they err on the side of falling back to their comfort zone whenever things get tough. We all do this. It feels good to spend time in your area of competency and it feels hard to spend time outside of it. If you feel very comfortable as a tech lead, and as an engineer, when you get exhausted and overloaded as a manager, your tendency is going to want to be to go back and just write some code to clear your head. That’s where people give you the advice to stop doing technical work. It’s bad advice. It makes your skills decay a lot more quickly. It loosens your overtime. The ties of empathy that you have with your team grow weaker. It’ll be harder to get back in the flow if you do want to be an engineer. I think that the right advice to give here is a subtler version of this. Stop writing code in the critical path. Don’t do anything that people are going to be waiting on you for, or depending on you for in order to get their jobs done. Keep looking for little ways to contribute. Pick up little tasks, Jira tickets, whatever.

My favorite piece of advice for managers is, don’t put yourself in the on-call rotation. Because then, that’s the critical path. You’re going to be blocking people. I remember doing this myself. I was like, I want to keep hands-on, I’m going to stay in the rotation, help my team out. As I got busier as a manager, what ended up happening was, it ended up placing an unfair burden on my team. This was at Facebook. If I was in like some performance review meeting or something important, and I got paged, I’d have to ask someone on my team to cover for me. Even when other people weren’t on-call, they ended up having to do work just to cover for me. My favorite piece of advice here is not to put yourself in the on-call rotation. Do make yourself the first escalation point of first resort. Not last resort, first resort. If your on-call has had a tough night, that they got paged a few times, put yourself in for the next night. Make sure that everyone knows if you’re on the weekend, and you want to take your kids to see the movies. Put me in, I’ll cover it for two or three hours, no problem. If you want to take a long car drive, anything you need to do, I’m your person of first resort. This has a bunch of benefits. It helps you stay sharp. It keeps your finger on the pulse of like, what is it really like to be an engineer here? How painful is it? Is my time being abused? Is my sleep being abused. It’s just such a relief for your team to have someone like that because you’re burst capacity. They don’t have to do complicated tradeoffs or make sure that they’re giving as much time, each person they’re asking to take over for them. It makes things a lot less complicated. It means the on-calls becomes easier for everyone. They’re very grateful. It earns you a lot of credibility and a lot of love.

You Can’t Be an Engineering Line Manager Forever

If you become an engineering manager, I talked in the beginning about how there are two primary pathways. One is to be the top dog engineer who becomes manager. The other is people become a manager, and then just stay a manager forever. I don’t think that that’s a good choice. I don’t think that you can really just be an engineering line manager forever. I think it’s a very fragile place to sit long term. You can’t be an engineering manager forever. I just don’t think you can be a very good one. You get worse at it. As your tech skills deteriorate, you’ll find yourself in the position of having to interview for new engineering manager jobs, and not knowing the tech stack. You’re slowly going to become one of those managers that’s just a people manager and doesn’t have enough domain experience to resolve conflicts, or to evaluate people’s work. If two people on the team are each claiming that the other one is at fault, how do you figure out who’s telling the truth, or if it’s broadly shared? You need to stay sharp enough. This means periodically going back to the world to refresh your skills. You should not ever plan on being a tech lead/manager, especially not long term.

This blog post that I linked to by Will Larson, is the best one I’ve ever read on why this is so bad for your team. His take on it is much more about that the tech lead manager is a common thing that people do to ease engineers into management. You’re a tech lead manager with two or three direct reports instead of six or eight direct reports. You don’t actually get enough management time to become better at your management skills. That’s his argument. I think it’s a good one. My argument is that from the perspective of your team, you’re taking up all the oxygen. If you’re the tech lead/manager, as a manager, it’s your job to be developing your people and building them into the position of tech lead. It’s not your job to sit there. The longer you sit there as tech lead/manager, the worse of a tech lead you’re going to become, and the more you’re starving your own team of those growth opportunities. While it’s sometimes unavoidable, or natural in the short term, it’s not a stable place to sit and it’s not a good place to sit.

Management Is Not Equal to Leadership

Every engineering manager who’s managing for a couple years, reaches this fork in the road, and you have two choices. Either you can climb the ladder, and try to be promoted to senior manager, director, VP, or you need to swing back and go back to the well and refresh your technical skills. That’s a fork in the road. The reasons for the decision is because, first of all, management, we talk a lot about technical leadership and technical management. Those are not the same thing. Leadership does not equal management. There are lots of ways to have leadership in a technical organization, that do not involve management. I think of management as being organizational leadership, and engineering as being actual technical leadership. Obviously, there are areas of overlap. You can’t be a great technical leader without having some organizational work. You can’t be a great organizational leader, without having some pretty sophisticated technical leadership. What’s important here is for this to be a conscious choice for you not just to slip into it, because managers in particular, you’re getting promoted. This feels good. It feeds your ego. You have this sense of career progression. It always feels great for someone to be like, I see more in you, would you like to be a director? Yes. Managers in particular have this tendency to look up 10 years later or so, and realize that they weren’t making the decisions because it made them happy. That, in fact, their decisions have made them less employable, and less satisfied. When you’ve been a manager for 10 years, it’s really hard to go back and be an engineer. You’re locked into that decision, in a lot of ways.