Transcript

Cockcroft: My name is Adrian Cockcroft. I’m going to talk about adding sustainability concerns to development and operations. I’m calling this DevSusOps.

Why Sustainability Matters

Why does sustainability matter? You may have various different thoughts about this. I think I’ve got most of them here. The definition of sustainability is really around leaving the world habitable for future generations. That’s the essence of the United Nations definition of sustainability. The reason it matters to most companies is regulatory compliance. Particularly in Europe, the regulators are saying, you’ve got to measure and report your carbon footprint and other sustainability risks. In the U.S., we’re moving in that same direction, and around the world, wherever you are, you’ve got regulation, saying you’re going to have to figure out what is the sustainability posture of your organization. Then there’s market transition risks. If you think of companies that own gas stations, or make parts for gas driven cars, that market is transitioning to electric cars. That’s a market transition. If you own a coal fired power station, you’re in a market transition. It’s any time that the market is changing as a result of the transition to a more sustainable future. You have a market transition risk, if you’re selling products that are affected by that market transition. Then there’s physical risks to business assets. If you own property at sea level, in very high temperature areas where it’s getting hotter outside, you try to move freight down rivers that are drying up. There’s all kinds of physical risks that you might have. Sea level rise is one that’s affecting the coast. There’s a lot of weather and high temperature related physical risks to business assets from climate change.

The other thing that you may have is products which are branded in some way to be green. The market positioning, you need to stand behind them, and walk the talk, and actually build green products in a green way. One thing that you can’t really underestimate, I think, is employee enthusiasm. Many of us have children that come home from school and say, what are you doing to save the world so that I have something to live in? That’s a big motivator. I’m a little older, but my kids are grown up. It really matters, what are we doing for the future. There’s a lot of personal investment in this, way beyond what you’d expect for just a cost optimization exercise. People get much more invested and excited about a carbon optimization exercise. As we move into a more sustainable future, we’re actually starting to see costs come down either now or you’re seeing future cost reductions. The cost of renewable energy is now lower than the cost of fossil fuels, fossil-based electricity. We’ve got current payback right now. The cost of operation of an electric car is less than the operation of a gas car now, although the upfront price is a little more. Over time, you see in the future, we’ll see electric cars being cheaper than gas powered cars even to buy in the beginning. Then, for some organizations who’ve got a bad history of working in climate change, like fossil fuel companies, they’re concerned about the social license to operate. Are people still going to want to go and work there, want to buy products for them if they’ve got a bad reputation around sustainability?

What We Can Do About Sustainability

What can we do about it as developers and operations people? On the development side, we can optimize our code, choose faster languages and runtimes. Pick more efficient algorithms. Use faster implementations of those algorithms. Things like simdjson, for example, is a super-fast way of processing JSON. Reduce the amount of logging we do. Then, reduce retries and work amplification by getting our retry algorithms worked out. That reduces the overall workload. That’s on the developer side, the way you set up your application. Then, on the operation side, whether you’re a DevOps engineer doing development and operating it, and you run what you wrote, or whether there’s a separate ops team, there are more operational concerns. You want to run the code you’ve built at a higher utilization. That might require tuning the code so that it can run at higher utilization, but you want to run at higher utilization. You want to use a lot of automation for things like autoscaling. You want to relax any over-specified requirements. You may have pushback on things that look either expensive or high carbon, and say, do we really need to retain data for forever? You might want to archive and delete data sooner, deduplicate data. Then the thing that you don’t normally think about is, choose times and locations carefully. If you run something at midday, there’s a lot of excess solar capacity, the grid is very green. If you run stuff at midnight, then you’ve got a lot more fossil fuel in the mix. That’s really the time-based thing. Then, location. Some locations, say, if you run things in France, there’s lots of nuclear energy. It’s a very clean grid from a point of view of carbon emissions. If you run things in Singapore, there’s a lot of carbon in the grid there. You end up with a very high carbon location. You go pick those things. Those are things that we’ll talk a little about later, but are not the normal concerns.

Almost all of these things are directionally the same as saving dollars. If you just make your system more efficient, you’re saving money, as well as saving carbon. I say almost all cases, because there are a few situations, say some regions which have lower carbon may cost a little more than other regions, if you look at a cloud provider. Migrating a workload, you might spend a little bit more but reduce carbon. That’s one of the few corner cases that you might see. The main thing is, even though you’ve got directionally saving money saves carbon, but the actual amount of carbon per dollar varies a lot. You have to understand whether saving a dollar of compute, or a dollar of storage, or a dollar of a service, what’s the carbon impact of that?

How to Measure Carbon

I’m going to spend most of this talk focusing on how to measure carbon, and see if I can figure out how to get the right mental models into your heads about how to think about it, the terminology, the way these things operate, so you can figure out in your own work, how to measure carbon, how to work in this space. We’re used to reporting and optimizing throughput, latency, utilization, capacity. We’ve started adding cost optimization to those kinds of things. Carbon is really just another metric for monitoring tools to report. We’re starting to see a few monitoring tools with carbon as a metric within them. What we’re really seeing is regulators and market pressure causing companies to have to report carbon and decarbonize their products and services. These are two separate things. Reporting carbon is something that the board has to do a report and sign off, and auditors come in. Every quarter, you do a financial statement, you’re going to have to put carbon in that financial statement alongside the financial numbers in the future. Those are audited numbers. What you need to do to do that is a little different than the information you need to decarbonize products and services.

Economic Model for Carbon

Do you know how much carbon your company emits for data processing and hosting per year? Most people don’t really know. How can we get to an answer? What you may know is your company budget. What’s your IT budget? Most people have some idea, whether it’s a million dollars, $10 million, or $100 million, or whatever. It’s somewhere in that ballpark. What you can do is for every million dollars you spend on IT, or whatever you define as data processing and hosting, it’s 159 metric tons of CO2. That’s the economic model. That’s just a rule of thumb you can do. If we’ve got a $10 million budget, we’re probably doing 1000 to 2000 metric tons of carbon. You’re in that range. Where does that number come from? If you go and search for carbon factors, you’ll find places like this, climatiq.io, you can go on this website, you can search. You can find that there is a standard number which is provided by the EPA. This is a government provided number, for 2020. If you are doing your carbon report for 2020, you go to the EPA number, and you find it’s 0.159 kilograms per dollar, which is the same as 159 tons per million dollars. You also notice this is calculated from 2016 data, which is a bit worrying. It’s a little bit out of date. Also, that it includes the entire supply chain, cradle to shelf, meaning all of the materials used to make it as well as the energy used to operate it, all the way through. This is quite an interesting number. It’s a very average number for the entire industry. If you have nothing else, you use this number.

The economic model for carbon, basically, you take your financial report, you break down the spend categories, find the right emissions factor, multiply and accumulate. The good thing about this is really everybody uses these models. Most of the carbon numbers you see out there that people are reporting are largely based on economic models. It’s just the way the world is. It gives you a big picture, approximate view. You can always get the input data. The industry standard emissions factors are available, some of them are openly available. There are some where you might license them to get some more specific ones. Auditors can trace the calculations easily. It does estimate the entire life cycle. That’s the good. The bad is it’s a really coarse model. Some of the factors are based on old data, in fast-moving areas like IT, they may not be that accurate. It can be hard to actually pick the right factor. This is one of the hardest things is finding, how do you categorize things and pick the right factor? It’s not trivial. Then this other problem is if you spend more, let’s say, you go and you buy some green product, because it’s greener, but you spent more on it. If you don’t have a different factor for it, then your reported carbon will go up just because you’re spending more. Effectively, carbon optimizations have no effect. The ugly thing here is if you do this for one year, economic model, and then you come up with a more accurate measure the next year, it could be quite a lot higher.

Recommendation here. Start here, use spend when no other data is available, use economic models to figure out where to focus efforts. If you look at your entire business, you’re going to see, what do you work on? Are you working for a SaaS provider or a bank where almost all your costs are people and IT and office buildings. In that case, maybe most of your carbon footprint is IT. I did a talk with Starbucks, earlier this year, or late last year, most of their carbon footprint is dairy, it’s milk. Their IT component is a very small piece. If they can use a little bit more IT to use that to convince people to maybe use oat milk instead of dairy, that actually makes a bigger difference, like a small percentage change in Starbucks’ end users from dairy to real milk to oat milk, will actually make more difference than their entire IT budget. You have to think about, what is the real carbon footprint of your company? Don’t just focus on the IT component.

Scopes of Carbon

I’m going to now explain something called the scopes of carbon with some slides I made while I was at AWS. The first thing is the fuel you consume. You count whoever owns the fuel when it’s being burnt. You buy gas, you put it in your car, you drive it around, that you’re now doing scope 1 emissions for whatever you put in the car. Anything you burn in your fireplace or gas used to heat your home, anything used for cooking, that’s scope 1. The way to get rid of scope 1 is to electrify everything, and then figure out how to get renewable electricity. Scope 2 is really the energy used. This is the energy where it’s consumed, but you’re not burning the fuel yourself. Somebody else burnt the fuel, sent you electricity. You have the grid mix, which is the mix of power, which is either renewable or fossil fuel. You could break it down. Those are the two main categories. What you want is carbon emitting and non-carbon emitting. Nuclear is good, because it doesn’t emit carbon. Nuclear isn’t really renewable but it counts as zero carbon. That’s the way you look at the grid mix. Then you look at your location, so your house, you’ve got a heat pump, solar panels, batteries, electric car. You’ve managed to convert that house to be all electric. Then if you can run the house off the batteries and the solar panels, you’re basically getting your scope 2 to be very low carbon. Then, if you’re doing cooking, you should switch to induction and electric cooking, because also gas ranges cause pollution and things like that. Some of the benefits aren’t just carbon, there’s other things that make it better to move off of fossil fuels.

Scope 3 is where it gets really complicated, depends an enormous amount, what business you’re in, it’s your supply chain. The point here is that say you had part of your business that was emitting a lot of carbon. You said I’m just going to buy that as a service from somebody else so I don’t have to count that as my carbon. That’s part of your scope 3, so you can’t get out of your carbon emissions by just offshoring it and sending it out and pushing it out to suppliers and say, I don’t own this thing. Any business that you don’t own, which is supply chain, and also the carbon your consumers emit to use your product also can count. In some cases, the inventory, the things you own, those things count as scope 3 as well. Think about this as pretty complex and extremely dependent on what business you’re in.

If we look back at data centers, really the only scope 1 you’ll see in a data center environment is a backup generator. They run diesel, mostly. What we’re doing to decarbonize those is put in larger battery packs, so that diesel is really a secondary backup, doesn’t get used very often. Also, move to biodiesel and fuel cells and other things like that, which can be fed by cleaner energy sources. It’s possible to work on that. It’s a tiny component of data center energy. Backup generators really don’t run that often. Scope 2 is this mix of electricity sources coming into the building. For a data center, scope 3 will be the building itself, the racks coming in. Anything used to deliver the components to physically put up the building, that’s all going to be your scope 3. If you look inside the data center, you can see there’s cooling, power distribution, heat, there’s a lot more going on there. Ultimately, your suppliers need to report scope 1, 2, and 3 to you, and then you need to report scope 1, 2, and 3 to your consumers. This is all defined by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol. You can have many happy hours reading this website to figure out for your particular business, what you have to do.

Process Models for Carbon

We’ve talked so far about the economic models, just using financial data to feed the carbon data. If we want to get a bit more accurate, what we need is a process model where the units are the materials you’re using, or the kilowatts of energy you’re using. The process model, you measure the materials. You find the right emissions factor, multiply and accumulate. For example, diesel, and gasoline, and jet fuel will have different emissions factors, even though they’re all measured in gallons, or kilograms, or whatever. This is called a life cycle analysis. That’s what that cradle to shelf component of that metric I highlighted earlier was talking about. What you’re really wanting to do is look at manufacture and delivery, which is your supply chain, your energy, which is your use phase. Then, what do you do once you’re done with it? How do you dispose of it? Do you recycle it? What’s the energy consumed there as well? The good thing about these models, they exist. It’s a well-defined methodology. LCA has standards around it. People are trained in it. You can hire people or consult with people that can generate these models. They’re reasonably detailed and accurate. Particularly for the use phase, energy data is fairly easy to get. When you do an optimization, it really does reduce the reported carbon, so you’re in the right area. Auditors can trace those calculations.

The bad thing is models are really averages for a business process. This is not going to tell you the actual carbon emitted by one machine in your data center running one workload, it’s going to give you an average for the whole thing. It’s still quite a lot of work to build an LCA model. It may be more expensive than you’d want to spend to hire the right people to do it. The supply chain and recycled data is particularly hard to get. Quite often, people build these models, and they just do the energy part. They don’t think about the scope 3 part, or they just don’t get to it because it is hard. Then they just report carbon. The ugly part here is some people just really focusing on energy use and report, we’re green because we’re 100% green energy. Then get surprised when saying, but all of that hardware you’re using emitted an enormous amount of carbon when it was being made, and you have to count that too. What you should do is use the economic models to tell you where most of your carbon is, then build process models for those. Start with energy, but don’t forget the rest of the life cycle.

Measuring Carbon Emitted by a Workload – How Hard Can It Be?

How hard can it be to figure out how much carbon is coming out of a workload? Here’s a zoomed in look at that data center. You get grid mix from your local utility bill, which you usually get a month or so after you’ve used the electricity. That’s annoying because that means you don’t know what today’s energy mix is, you just know what last month’s was. Then, there’s power purchase agreements, or renewable energy credit purchases, which is basically affecting your grid mix. Then you have power usage efficiency, which accounts for losses and cooling overhead as the power that comes into the building is delivered to the rack. The machine may use a kilowatt, but there might be 10% extra energy which went to the cooling and distribution area, so 1.1 kilowatts had to come into the building to provide that energy. Scope 2 carbon is going to be the power mix, multiplied by the PUE, multiplied by how much capacity you use, and then the emissions factor per capacity. The amount of CPU you used or storage. Then you’d have a different emissions factor for CPUs and storage of different types, networking, whatever.

A few problems here. First of all, these utility bills are going to be a month or more late. The further you get to the developing world, the harder it is to get this data, and the more delayed it’s likely to be. Then, I mentioned power purchase agreements. These are contracts to build and consume power generation capacity. Amazon has over 15 gigawatts of these. Basically, Amazon contracts with somebody else to say, we’re going to give you some money and you’re going to build a wind farm or a solar farm. We’re going to buy the energy from that farm at a certain price, usually lower than the typical price that you’d get if you just went to PG&E, and say PG&E is whatever it is, 20-something cents per kilowatt hour. You could get much less than that if you build your own solar. It saves money, and you’re funding the creation of a new solar, wind, or battery plant that would not otherwise exist by entering into this contract. This is good, because it’s what’s driving a lot of the rollout of solar, wind, and battery around the world.

If you just fund building your own solar array, or wind farm, and you’re just selling that capacity to PG&E, or to whoever comes by, one of the things you can do is sell additional, the fact that it’s renewable, you can charge a little surcharge, so say this is renewable energy and I’m going to allocate that to somebody. Companies can go and say, I want to buy some renewable energy credits, and they’re going to get used once. Once everyone’s bought all the credits for all of the solar that’s kicking around in the market, you’re out. There’s only a certain amount of this capacity available, because it’s the open market for otherwise unused power. It’s not quite as good as a PPA, but it’s still good. You’re still funding somebody with a bit of extra money for the fact that they built a solar farm, and it makes it more profitable. It means that, ultimately, more solar farms get built or whatever. It’s not as direct as a PPA. What typically happens is companies do as many PPAs as they can. Once they’ve got all of those in place and this is ok, we’ve done everything we can possibly do, we have a bit more money, we’ll buy a few RECs on the side. It’s a much smaller proportion than the PPAs for the large cloud vendors. You’re buying a few RECs to just top it up and help things out.

The grid mix itself, another problem, it’s not constant. It’s going to change every month. Whenever you look at a carbon number, you have to say, when was that carbon number? There isn’t just a carbon number, you have to say, was that in what year, what month, even down to what hour was it? Because now we’re starting to see hourly 24 by 7 grid mix coming from some suppliers in some parts of the world. This is going to take a long time to get around everywhere. Google Cloud Platform really started diving in on this. Azure are working on it. AWS have not said anything about it yet, but hopefully working towards it. There’s also a company called FlexiDAO working in this area, you could go look at what they’re doing. They’re working with GCP, and Azure, and other people. One of the problems here is that the cloud carbon footprint tool doesn’t include PPAs, it really only runs off the public grid mix. It can’t really know how much you get from the PPA, because that’s private information that isn’t shared. It’s all difficult.

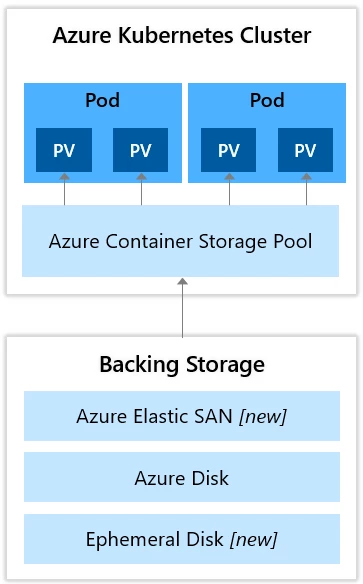

If we look at PUE, not well standardized. The different architectures of different data centers mean that you can come up with differences that really aren’t comparable. Like, do you have a centralized power distribution system or a distributed one? Are you delivering high voltage AC or DC all the way to the racks? Do you have your batteries in every rack or centralized? It actually makes a difference to the way PUE is calculated, how you do that. Lots of discussion about that in this blog post. If you look at the capacity, dedicated capacity is relatively easy to account for maybe in a data center environment. Once you get into the cloud, it’s really hard to figure out how much you’re using of a shared service network equipment, slices of instances, virtual machines, really tricky. You can get roughly in the right ballpark, and those are the factors we’ve got, but you can’t really know what you’re doing. Then there’s this other problem. If you’re operating a multi-tenant service and want to report the carbon to your customers, then you have a problem of figuring out how much capacity to allocate to each customer, how much is overhead that you should own yourself. All the cloud vendors basically are having to solve this problem for their customers, and all of the SaaS providers running on the cloud, are then having to do it downstream.

Then, we get to the emissions factor per capacity. You need to know how much power every instance type, storage class, or service uses. Depends on utilization, overheads. It’s actually very difficult to figure this out. You can get some averages. There’s some data for some systems. The cloud providers roll all this up, and some provide some estimates. All of these things are estimates that are in roughly the right ballpark, is probably what you’ll get. I wouldn’t worry about, if you get a number for an instance that looks vaguely similar on one cloud provider to another cloud provider, I just use the same number for the emissions factor.

Carbon Audit Reports

If you’re going to report carbon, and it’s going to be reviewed by the board and the auditors and all this stuff, you really need to be using the cloud vendor reports. AWS and Azure and Google have those kinds of reports available. If you’re on-prem, you need to use economic models, probably, or build your own models. Auditable data has to be traceable, and defensible, but, as I mentioned, is too coarse and it arrives too late to be useful for optimization.

Methodologies for Reporting Carbon, Location vs. Market Based

Then on top of that, there’s two different ways of reporting carbon. I’m going to try and explain the difference between location and market-based metrics. If we look at location based, this looks at a particular building, and it says, what is happening at this building? There’s the grid mix coming in. If I use an incremental extra kilowatt hour of energy, how much additional incremental carbon will be consumed, supplying me that extra incremental kilowatt hour of energy? That’s the idea for location based. It comes up with higher numbers for carbon than the market-based method. It’s typically what’s happening. The Google data, hourly, 24/7 data is based on this. The problem with it is that the way it’s defined it does not take into account the power purchase agreements, which the cloud vendors are spending enormous amount of money on. What’s used in that case, is a market-based method that says all of the electricity in a market is all the same. You pump electricity, you push electrons into the grid, they pop out of the grid. If I have 100 megawatts I’m putting into the grid from this power station here, I can use it over here, and it’s fine. It just flows through the grid. I want to take into account the fact that I am generating this power, and it’s my power. I’ve got the PPA or the REC in place. The market-based method includes the PPAs and the RECs, and you effectively are creating a custom grid mix for your data centers. It’s usually averaged over a month.

The reason this matters, is that basically your AWS and Azure data is regional market based. They take into account PPA generation and RECs that are within the same grid, so that electricity flows together. Google’s had a claim since 2017, that said that they generate more energy than they use. They’re taking that on a global basis, which was a bit dodgy really, because they were basically saying we generate more power than we use in the year. They were basically over-generating extra power in USA and Europe and saying that’s good, but in Singapore, you’re still emitting a lot of coal powered and oil powered fossil fuel generation. They were saying on average, across the whole world, it made sense. It doesn’t really. It makes sense if you do it at the regional market level where the grid is connected. Then Google went to this more current data, is location-based API, and 24 by 7, their API work. You can’t compare the numbers between AWS, Azure, and Google because of this. The Google data is more useful for tuning work, and their API is really the most useful API if you’re trying to build some tooling on this right now. Over time, as the utility grid decarbonizes, it matters less. If you’re in France, where it’s almost a completely carbon-free grid, it really doesn’t make much difference. It’ll make a bigger difference if you’re in Asia.

What You Can Do Today

What can you do today? For workload optimization, we need directional and proportional guidance. The Cloud Carbon Footprint tool up next is open source, uses billing data as input, maintains a set of reasonable estimates or guesses for carbon factors. Your mileage will vary as to the actual data you get out of that. I wouldn’t put it in an auditable report, but it’s useful for tuning. The Green Software Foundation has come up with the Software Carbon Intensity standard. This is a model for reporting software impacts per business operation, like grams of carbon per transaction, or per page view, or whatever. They’re defining that standard. It’s worth going to look at that. AWS has the well-architected pillar for sustainability, which I helped write and get out about a year ago. It’s the guidance on how to optimize development operations for carbon. It’s like some good advice in there.

Looking to the Future

Where’s all this going to be in a few years’ time? I think most monitoring tools are going to report carbon as the data becomes more available. Eventually, all the cloud providers are going to have detailed metrics. Google’s got detailed metrics now. Microsoft has some if you know where to look. AWS really doesn’t have detailed metrics at this point, but I think we’re all going to get there. Then, the European, U.S. cloud regions are pretty close to zero carbon now, if you take the PPAs into account. There’s a lot of generation offsetting the energy used. Everyone has the same problems. The Asian regions probably in the next few years are going to get to zero carbon. It’s just regionally been very difficult to get solar and wind projects in place.

Questions and Answers

Synodinos: One of the questions has to do with resources that people can use to follow up. You mentioned some websites. Is there any literature, like how we have the definitive books for performance, for scaling? Is there any book about this topic yet?

Cockcroft: I think the best place to look right now is the well-architected guide that AWS put out, and more recently, Microsoft has also put out a well-architected guide for Azure. The Microsoft one is based off of the Green Software Foundation recommendations, which are very similar. These are all very close. People are basically looking at the same things. There are some references to some of the way to think about it. There’s obviously stuff that’s specific to particular environments, like some cloud vendors, like AWS have Graviton processers that use less power. Also, I recently noticed that AWS is now listing the regions that have 95% or better clean energy, which are basically what I said is Europe and Asia. Europe and U.S. have better than 95% for 2021. It’s been improving since then. The Asia regions are not included in that list. If you just go to Amazon’s website, and search for sustainability, there’s a section there about cloud.

If you’re worried about the energy use of your system, you should be worrying about any energy use you have in Asian regions, or outside Europe and the U.S. There’s Africa and Arabian ones, which are not on that list at this point. Over time, the number of regions that are 95% or better green, is going to go up. By 2025, the goal is to have everything at 100%. That’s what AWS is doing. You can go get data off their website. The Green Software Foundation’s collecting useful data, and making sense of it. Then I’m just looking around for really efficient libraries. Things like simdjson, is a good reference there. The Zstandard compression algorithm saves you about 30% on stored capacity. It’s more efficient on reading data back, decompressing in particular. There’s a sort algorithm that Google came up with recently and posted, that’s built a little bit like simdjson. It’s just the fastest possible implementation of Quicksort or whatever, if you want to sort things. Run using the languages that are in your environment, just go and find these default libraries in your language, maybe look for some more efficient ones, for the key things that you use a lot.

Synodinos: To some extent, for these things to matter, there needs to be more of an organizational change towards practices like that. I believe a question that frequently comes up when we talk about sustainability is, how can an engineer or a technical leader either in their team or as part of a larger organization, convince that organization to adopt more sustainable practices? Have you seen any ways that can help with that transition?

Cockcroft: You’re going to have management saying, we need to figure out how to measure and optimize this because we got to report it to the Street as part of our quarterly numbers. That’s driving it from one end. There’s individuals who are interested, bottom-up, and a bunch of people are going to be building data lakes, and trying to gather this data together. That’s a workload which is starting to appear. We’re in the middle of the AWS re:Invent conference, and there’s a lot of talks there on sustainability. If you go to YouTube and look at AWS Events, and just search for sustainability, most of them start with SUS something, sort of SUS302, and things like that. There are some good talks. Some of them are companies talking about how they’re measuring their carbon. Then there’s some other recommendations in there. A lot more this year than there was last year. Last year, we had four or five sustainability talks. We had a fairly basic track that I helped organize. I’m no longer working at Amazon, but the track has two or three times as much content in it. There’s a good body of content there. If you look at similar events, from the Google Cloud, and Microsoft, all of the major cloud providers now have a lot of examples and content around sustainability as part of their deployments. The efficiency and the ability to buy green energy is really driving this, and the cloud providers are much more efficient than on-prem. You have to do a lot of work on-prem to get close. That work generally hasn’t happened.

Synodinos: Do you think cloud providers could open or move operations to countries where clean energy was more available, such as Africa and South America, where the availability of solar and wind energy is greater?

Cockcroft: Yes, they’re doing that. What they’re doing is they’re putting in solar, wind, and batteries. AWS recently launched a region in Spain, but it took quite a long time to get the region up and running. They announced it two or three years ago, and they immediately put in solar and wind. The energy environment went in and came online before the region came online. Same thing happened in Melbourne, Australia. The Melbourne region has a lot of local solar, and the Sydney region in Australia doesn’t. It’s got a lot more coal. It’s being done jointly, as the cloud providers are planning their regions and rolling around the world, takes a while to build a building, takes a while to put up a wind farm. They’re doing them all in parallel and all going as fast as they can.

Amazon is a little different, because it’s actually solving for the whole of Amazon, not just for AWS. AWS is a minority of Amazon’s energy use. They use a lot more energy in the delivery and the warehouses and that side of the business than they do with AWS. Whereas Google and Microsoft are primarily online businesses, most of their carbon footprint is from IT. If you look at the totals, Amazon is like about four times the carbon footprint of Microsoft and Google. That isn’t AWS, that’s primarily the rest of the business. They’re solving for the big picture. This is one of the things to think about, don’t solve for your little piece of the picture, because you may be suboptimizing something outside. You’ve got to take the scope 3 big picture view of like, what is the entire environment? How do you solve for less carbon in the atmosphere for everybody, rather than making the numbers go down for a particular workload somewhere.

Synodinos: Do you think there are other perspectives than cloud architecture? Thinking about sustainability, also in terms of waste, maybe.

Cockcroft: Energy use is the one that’s really driving carbon, which is driving a lot of climate change, climate crisis. There’s also water. AWS just did an announcement this week about a water commitment, something like clean water by a certain date everywhere in the world, 100% clean. A lot of the AWS regions, they take in wastewater that is not suitable for drinking and irrigation, they use it for cooling. Then they process it before they put it back, and it goes straight into the fields as agricultural water that’s cleaned up. There’s examples like that, where they do use a lot of water in data centers. There’s another one, I think it’s Backblaze. They have a data center that’s on a barge in a river, and they take water in from the river and they put slightly warmer water back into the river. As the river flows past, they just warm it up a little bit. Pat Patterson was telling me about that. Then there’s other examples like that. That’s water.

Then you’ve got plastics, trying to reduce the amount of plastics, amount of garbage that’s generated. They call it the circular economy. You want to have zero to landfill. There are some sites, like the new Amazon headquarters is set up to be a zero to landfill. The Climate Pledge Arena in Seattle, part of their setup is to be zero to landfill. It requires quite a lot of work to get rid of all of the things that normally just get trashed. People are working on those things. They’re not affecting sea level rise through that, but they’re affecting the amount of garbage in the sea and things like that. You can think about the whole big picture.

The other thing that’s important is really more about a just transition. The benefits of modern technology, and the wealth of the world tend to go to a few. The problems caused by climate change and pollution tend to be disproportionately to people who are underprivileged. There is this very specific effort around making this a just transition. We’re building a nice big power plant, but we’re going to put it in the poor neighborhood, because the rich neighborhood can lobby to not have it there. Those kinds of things are happening around the world. I wouldn’t say we’ve stopped doing those things, but it’s getting more visible, and there’s more pushback on them. That’s the other part of sustainability really is about making it a just transition so that everybody gets a better world in the future, rather than it being disproportionately for the more wealthy people in the developed nations.

Synodinos: Recently, I came across a New York Times article that was talking about something called Tree Equity, and about how rich neighborhoods actually have lower temperature during heat waves, because they can afford more trees, people are watering gardens, they have plants.

Cockcroft: There’s a whole lot of greening cities where there’s a lot of concrete and it gets very hot. If you plant trees along the roads, and get rid of the cars, it actually lowers the temperature of the city, like your air conditioning doesn’t have to work as well. Trees are enormously good air conditioning systems, it turns out. They absorb the energy. They keep it cool. They keep the humidity up. A lot of examples there as well.

Synodinos: Talking about the big picture, do these cloud footprint audits clash with AI foundation models that may make use of a lot of power to train models.

Cockcroft: You have to take those into account. If you’re doing very large AI modeling, you’re training for Siri, or Alexa, or Google Voice, you’re running some very big heavyweight jobs. Facebook runs some very big jobs too. The large companies that are doing a lot of image classification or video classification, are burning a lot of compute power, and they are buying clean energy to run it, and trying to use more energy efficient systems. There are more specific CPUs, like Trainium, or the Google Tensor processor are more efficient than some of the GPUs, the standard off-the-shelf GPUs that were really designed for gaming and supercomputer type applications. We’re seeing more specific processor types, which give you better power consumption for the energy. The supercomputer world has a green benchmark, the top 500 most green supercomputers based on the amount of compute they get per energy usage. There’s some focus on it, and it really applies a lot. Big AI systems definitely look like that. It’s a concern. The people that are running those big systems generally are also concerned about the energy and are taking care of it pretty well.

See more presentations with transcripts