Month: August 2023

MMS • RSS

Check out the companies making headlines after hours.

MongoDB — Shares of the database software maker gained 5% in extended trading. MongoDB reported earnings of 93 cents per share, excluding items, on revenue totaling $423.8 million in the second quarter. That came in ahead of the earnings per share of 46 cents and $393 million in revenue expected by analysts polled by Refinitiv.

Dell Technologies — Dell popped 7.7% after reporting second-quarter earnings that surpassed Wall Street’s expectations. The technology company reported earnings per share of $1.74, excluding items, and $22.93 billion in revenue, while analysts polled by Refinitiv expected earnings per share of $1.14 and $20.85 billion.

Broadcom — Shares of the semiconductor manufacturing company fell 4% after the company posted soft fiscal fourth-quarter guidance. The semiconductor company called for fourth-quarter revenue of $9.27 billion, while analysts polled by Refinitiv anticipated $9.275 billion.

VMware — The cloud services stock edged down 1.7%. VMware posted mixed earnings, coming out at earnings of $1.83 per share, excluding items, on revenue of $3.41 billion. Meanwhile, analysts polled by Refinitiv expected $1.71 in earnings per share and $3.46 billion in revenue.

Lululemon Athletica — Shares of the athletic apparel retailer gained nearly 2% Thursday after it reported sales and profits that beat Wall Street’s estimates. The company reported earnings per share of $2.68 and $2.21 billion in revenue for its fiscal second quarter, while analysts polled by Refinitiv expected $2.54 in earnings per share and $2.17 billion in revenue. Lululemon also said it now expects sales of $9.51 billion to $9.57 billion for the fiscal year.

Also on CNBC

After-hours movers: Nutanix, Dell, MongoDB gain following results; Broadcom falls – StreetInsider

MMS • RSS

After-Hours Stock Movers:

Eos Energy Enterprises, Inc. (NASDAQ: EOSE) 55% HIGHER; announced Project AMAZE – American Made Zinc Energy, a $500 million planned expansion and a significant milestone to build 8 GWh of clean energy storage production capacity.

Nutanix (NASDAQ: NTNX) 14% HIGHER; reported Q4 EPS of $0.24, $0.08 better than the analyst estimate of $0.16. Revenue for the quarter came in at $494.2 million versus the consensus estimate of $475.24 million. Nutanix sees Q1 2024 revenue of $495-505 million, versus the consensus of $487.22 million. Nutanix sees FY2024 revenue of $2.085-2.115 billion, versus the consensus of $2.08 billion.

Dell Technologies (NYSE: DELL) 8% HIGHER; reported Q2 EPS of $1.74, $0.60 better than the analyst estimate of $1.14. Revenue for the quarter came in at $22.9 billion versus the consensus estimate of $20.86 billion.

MongoDB (NASDAQ: MDB) 5% HIGHER; reported Q2 EPS of $0.93, $0.47 better than the analyst estimate of $0.46. Revenue for the quarter came in at $423.8 million versus the consensus estimate of $393.68 million. MongoDB sees Q3 2024 EPS of $0.47-$0.50, versus the consensus of $0.27. MongoDB sees Q3 2024 revenue of $400-404 million, versus the consensus of $389.12 million. MongoDB sees FY2024 EPS of $2.27-$2.35, versus the consensus of $1.55. MongoDB sees FY2024 revenue of $1.596-1.608 billion, versus the consensus of $1.55 billion.

HashiCorp (NASDAQ: HCP) 4% LOWER; reported Q2 EPS of ($0.10), $0.05 better than the analyst estimate of ($0.15). Revenue for the quarter came in at $143.2 million versus the consensus estimate of $138.22 million. HashiCorp sees Q3 2024 EPS of ($0.05)-($0.03), versus the consensus of ($0.04). HashiCorp sees Q3 2024 revenue of $142-144 million, versus the consensus of $141.74 million. HashiCorp sees FY2024 EPS of ($0.23)-($0.21), versus the consensus of ($0.26). HashiCorp sees FY2024 revenue of $571-575 million, versus the consensus of $567.59 million.

Broadcom (NASDAQ: AVGO) 3% LOWER; reported Q3 EPS of $10.54, $0.11 better than the analyst estimate of $10.43. Revenue for the quarter came in at $8.88 billion versus the consensus estimate of $8.85 billion. Broadcom sees Q4 2023 revenue of $9.27 billion, versus the consensus of $9.28 billion. Fourth quarter Adjusted EBITDA guidance of approximately 65 percent of projected revenue.

Restaurant Brands International Inc. (NYSE: QSR) 1% HIGHER; announced today that its Board of Directors has approved a share repurchase authorization (the “Repurchase Authorization”) pursuant to which RBI may purchase up to US$1.0 billion of its common shares over the next 2 years through September 30, 2025. This approval follows the expiration of RBI’s prior 2 year authorization to repurchase up to the same US$1 billion amount of its common shares.

lululemon athletica (NASDAQ: LULU) 1% HIGHER; reported Q2 EPS of $2.68, $0.15 better than the analyst estimate of $2.53. Revenue for the quarter came in at $2.2 billion versus the consensus estimate of $2.17 billion. lululemon athletica sees Q3 2024 EPS of $2.23-$2.28, versus the consensus of $2.23. lululemon athletica sees Q3 2024 revenue of $2.165-2.19 billion, versus the consensus of $2.15 billion. lululemon athletica sees FY2024 EPS of $12.02-$12.17, versus the consensus of $11.93. lululemon athletica sees FY2024 revenue of $9.51-9.57 billion, versus the consensus of $9.51 billion.

MMS • RSS

Subscription revenue grew 40% year-over-year to $409.3M, while services revenue was up 20% to $14.5M.

“MongoDB delivered excellent results in the second quarter, highlighted by 40% revenue growth, continued strength in new workload acquisition and record operating margin. The ongoing success of our new business efforts for Atlas (NYSE:ATCO) and Enterprise Advanced across our sales channels is a testament to the value of MongoDB’s run anywhere strategy which enables customers of any size to innovate faster and more efficiently,” said CEO Dev Ittycheria.

For Q3/24, the company expects EPS of $0.47-$0.50, compared to the consensus of $0.27, and revenue of $400-$404M, compared to the consensus of $389.12M.

For the full year, the company sees EPS at $2.27-$2.35, compared to the consensus of $1.55, and revenue at $1.596-$1.608B, compared to the consensus of $1.55B.

MMS • RSS

Couchbase Inc., a provider of cloud databases, is the most recent technology company to incorporate generative AI into its flagship product. For its database-as-a-service offering, Couchbase Capella, it unveiled a new feature it calls “Capella iQ”.

With AI-generated recommendations and sample code, Couchbase claims that it will make it faster and easier for developers to write SQL++ and application code. Everyone wants a piece of the rapidly rising technology known as generative AI.

It’s a unique kind of AI that was made popular by OpenAI LP’s ChatGPT and is capable of producing anything from original written words to speech and code. Complex business applications are powered by Couchbase Capella, a cloud-hosted variation of the Couchbase NoSQL database.

Read More: Couchbase jumps on the generative AI bandwagon with Capella iQ code generator

Check Out The New Enterprisetalk Podcast. For more such updates follow us on Google News Enterprisetalk News.

MMS • Claudio Masolo

On August 15, OpenTF Foundation released the OpenTF Manifesto after the announcement by Hashicorp, on August 10, to change the license from Mozilla Public License (v2.0) (MPL) to Business Source License (v1.1) (BUSL), on all future Terraform releases.

The main goal of OpenTF Foundations, as mentioned in the manifesto, is to maintain Terraform to a fully open source license and asks HashiCorp:

… to do the right thing by the community: instead of going forward with the BUSL license change, switch Terraform back to a truly open source license and commit to keeping it that way forever going forward. That way, instead of fracturing the community, we end up with a single, impartial, reliable home for Terraform where the whole community can unite to keep building this amazing ecosystem.

The MPL is a simple copyleft license.

The MPL’s “file-level” copyleft is designed to encourage contributors to share modifications they make to your code, while still allowing them to combine your code with code under other licenses (open or proprietary) with minimal restrictions.

On the other hand, the BUSL license which was invented by MariaDB, says:

The Licensor hereby grants you the right to copy, modify, create derivative works, redistribute, and make non-production use of the Licensed Work. The Licensor may make an Additional Use Grant, above, permitting limited production use.

In its FAQ about the BUSL license, HashiCorp clarifies some points by responding to some questions from the community. HashiCorp wrote that is allowed to use its products as a service internally in the organizations because:

The terms of the BSL allow for all non-production and production usage, except for providing competitive offerings to third parties that embed or host our software.

For competitive offerings, HashiCorp specifies:

A “competitive offering” is a product that is sold to third parties, including through paid support arrangements, that significantly overlaps the capabilities of a HashiCorp commercial product. For example, this definition would include hosting or embedding Terraform as part of a solution that is sold competitively against our commercial versions of Terraform. By contrast, products that are not sold or supported on a paid basis are always allowed under the HashiCorp BSL license because they are not considered competitive.

Two weeks after publication of the manifesto, which was subscribed by over 100 companies, and noting the decision of HashiCorp not to switch back the license as asked, OpenTF Foundation decided to create a fork of the MPL-licenced Terraform code and call it OpenTF and maintain it in the foundation.

The reaction of Kelsey Hightower, former Google developer advocate, about the decision of HashiCorp is:

The Terraform situation, and the community’s response, demonstrates the power of open source. The original maintainers made a decision a subset of their community doesn’t agree with, they forked the project, and will continue building in a foundation

Even more than 100 companies subscribed to the OpenTF manifesto, there are also companies not agree with the OpenTF Foundation initiative like dragondrop.cloud who share why they will not support it.

Possible Infrastructure As Code (IAC) alternative to Terraform are Pulumi or AWS cloud formation.

MMS • Courtney Nash

Transcript

Nash: I’m Courtney Nash. I am here to talk to you about rethinking reliability, what we can and can’t learn from incident metrics. I’m an Incident Internet Librarian at Verica. I’m a researcher with a long background at a bunch of different places. I used to study the brain. I think mountain bikes are the coolest technology we’ve ever invented.

The Verica Open Incident Database (VOID)

I’m here to talk to you about this thing I made called the VOID. The Verica Open Incident Database is a place where public software related incident reports are collected and made available to everyone and anyone. Our goal is to raise awareness and increase understanding of software-based failures in order to make the internet a more resilient and safe place. Why do we care about that? Because software has long since moved beyond hosting pictures of cats online to running transportation and infrastructure and hardware in healthcare systems, and devices in voting systems and autonomous vehicles. These modern online systems are expected to run 24/7 hours a day, 365 days a year. Those increased pressures that you all deal with, combined with software models of interrelated increasingly automated services that run in the cloud, have accelerated the complexity of these systems. As you already probably know, from direct experience, when those complex systems fail, they fail in unexpected and chaotic ways. We all have incidents. Yes, that is a dumpster fire with a dragon lighting a volcano on fire. I think more of what you face is probably more like Calvin and Hobbes, where there’s like a monster under the bed, and you’re never sure when it’s going to come out.

The really important point is that the tech industry has an immense body of commoditized knowledge that we could share in order to learn from each other and push software resilience and safety forward. If you’re at all skeptical about that, I get that, you might be. There’s historical precedence for this. It’s not our industry, it’s a different industry. In the 1990s, in the United States, our aviation industry was in a bit of a crisis, we had a horrible safety record. Significant high consequence accidents were happening on a regular basis. The industry collectively and from the ground up decided to get together and try to do something about this. A variety of pilots first from a number of different airlines got together and started sharing their incident data. They started sharing their stories and their patterns of what they were seeing. Eventually, more of that industry got on board, the regulatory bodies, the air traffic controller folks, a huge number of people got involved to share their incidents and find commonalities and patterns. Over the course of doing that, and obviously other activities, the safety record of our airline industry went way up. In fact, we didn’t have a significant incident until some of the Boeing MAX stuff of recent years happened. It’s possible to do it from the ground up as practitioners before even there were regulatory people show up. That’s important.

What’s in the VOID?

We’re trying to collect those kinds of incidents together. There hasn’t been any place in the past where we’ve had all of these, what you might call availability incidents. There’s a number of people who’ve walked this ground before me. I’m not claiming that this was my idea. I’ve just been fortunate enough maybe to get more of them together in one place. At this point, we have almost 10,000 public incident reports from over 600 organizations, spanning from about 2008 up until basically now in a variety of formats. This is important. We’re collecting them across social media posts, and status pages, and blog posts, and conference talks, and tweets, and full-blown comprehensive post-incident reviews, where you all sit down and write up a lot more information about these things. We want all of those because we want a really comprehensive picture of not just how you see these things, but how other people see them. Things like media articles are included in there as well.

Duration: Gray Data

What’s in there is a bunch of metadata that we’ve collected, things like the organization, the date of the incident, the date of the report, and a bunch of stuff. The thing we’re really going to focus on for this talk mostly is duration, and its relationship to a metric that is very influential in our industry, which is mean time to respond, or MTTR. First, let’s dig into duration. Duration is what I like to call gray data. It’s high in variability, low in fidelity. It’s fuzzy on, when does it start, when does it end? How are those things decided and recorded? It’s sometimes automated, often not. It’s sometimes updated, sometimes not. It’s ultimately a lagging indicator of what’s happened in your systems. It’s inherently subjective. We decide these things. We think they’re spit out of our systems, but that’s not really entirely true. The reality is, when you take all of these gray areas, and you use them as objective, and you average those, and try to think that that’s some key indicator of performance, you get one big gray blob. You’re not able to rely on that.

I want to show you a little bit of this gray data in action. These are mean times to respond that we have collected based on almost 7000s worth of incident duration data from the VOID. It’s really tempting to look at these and try to use them as some indicator, maybe Cloudflare and New Relic are just better at incident response, or maybe their systems are less complex, or they get lucky more often. No, these data are not indicative of any of those things. As you see, there’s a huge amount of variability across these even within a company across a certain amount of time, depending on the window in which you try to calculate something like a mean over these data. The problem with trying to use numbers like these derived from the gray data of duration is exacerbated by the inherent distribution of those duration data.

The Distribution Matters

I don’t know how many of you have actually looked at the distribution, charted a histogram of your incident duration data if you collect them. Let’s back up a little bit. This is a normal distribution, something you’re very used to seeing. It’s your classic bell curve. There’s a really clear middle. There’s similar curves off both sides. You can nail the mean in the middle. You can get standard deviations. You can do all kinds of super fancy statistical things with this. That’s not what your data looked like, based on almost 10,000 incidents that we have in the VOID. This is what your incident data actually look like. As this plays out, these are histograms of the distribution of duration data across a variety of companies that we have that have enough data to really do this, hundreds, at least of incidents. They’re skewed, you might notice. They are high on the left side of the graph, and then they drop down and they have a nice long tail there. The problem with skewed distributions like this is they can’t be described well via central tendency metrics like the mean. Some of you are going to start thinking, we’ll use the median, and we’ll get there. Even that when you have this much variability in your data means detecting the differences is also very difficult. That’s what a lot of times we’re trying to do. We’re trying to say, our MTTR got better. Our MTTR got worse, like what happened? It turns out, this just doesn’t have meaning.

We had looked at a report from an engineer at Google last year, who had a lot of data that looked very similar to ours. He ran a bunch of Monte Carlo simulations in this report that’s in the O’Reilly report that I showed there. He found that when he simulated a decrease in MTTR across a big chunk of Monte Carlo simulations, that there was so much variability in the data that it led to really like an inability to detect that change. It’s really, you’re subtracting 10% off your duration, you’re decreasing your MTTR. You run a bunch of simulations of the original data against those shorter durations, and you can’t actually detect a difference. I’ll show you a graph of this. What he found, and we also replicated when we did the same thing with more companies across even more incidents, that was even when you introduce improvements, you find that almost a third of the time the detected change in MTTR was negative. It’s a little counterintuitive, but let’s just say that means that things got worse. This is what those data look like. You subtract the original data from the changed data. A positive means that things have gotten better. These are our results replicating Davidovic’s Monte Carlo simulations. Anything on the right side means it got better, and anything on the left side means that it got worse, that your MTTR actually increased. What you’ll see is for a big chunk of most of those curves you see, there’s places where you think you got even better than 10%, and places where you might have gotten even worse than 10%. That’s really what’s important. There’s too much variance to rely on the mean. Those of you who’ve paid attention to distribution and knew a bit about these things, or a lot about these things, even, might say, we could use the median. We ran these simulations across the median data, and the results were incredibly similar. There’s still just too much variability and not enough sample size across most of these data to actually detect anything.

Sample Size Matters

Let’s talk about sample size. That company that had the big red one, they have the most incidents out of anybody, in all of the data that we had. They have enough data that you can start to maybe get some fidelity from things like mean and running these kinds of Monte Carlo simulations, and all of those types of things. That really means that the only way to get better fidelity of your incident data is to have more incidents. That’s really not what any of us wants. You have to get into the upper hundreds, almost thousands, to start seeing tighter curves, and being able to detect differences amongst things. Nobody wants that. We don’t want to have more incidents.

Summary of Duration, MTTR, and Severity

Just to sum up a bit on this, MTTR is not an indicator of the reliability of your system. I think this is a really common myth in our industry, that it tells you how reliable you are. There’s nothing reliable about those data that you just saw. You don’t want to use an unreliable metric to talk about the reliability or the resilience or any of those words of your systems. It can’t tell you how agile or effective your team or organization is, because you can’t predict these things. You definitely can’t predict the ones that are surprising, and they’re all surprising. The MTTR won’t tell you if you’re getting better at responding to incidents, whether the next one will be longer or shorter, or even how bad any given incident is. I want to spend a little bit of time on this, just a slight diversion. Because most people harbor some suspicion, like the longer ones are worse, or the longer ones aren’t as bad because we throw everyone at the bad ones, and those are done sooner. The longer ones are like, whatever, we can just let those run. Our data don’t show that either. We had something like 7000 incidents where we could collect the duration and the severity, these are mostly status pages from those companies. What you see in this graph is what it really looks like for most people. You have long ones that are more severe. They’re in the yellow, red. They’re the 1s and 2s. You have short ones that are 1s and 2s. You have long ones that are 3s and 4s, they’re green and blue, they’re not so bad. The look of this chart is what statistically we found. We ran a Spearman rank correlation, for anyone who really wants to get in the weeds, across severity and duration, and only two of the companies we looked at showed what anyone would consider to be super weak correlations between duration and severity, -.18, -.17 R values, they did have significant p values. In that up to 0.2, 0.3 range of correlational analyses, it’s a very small effect. Some you might see a little bit, but you also have to have a lot of data in order for an effect like that to show up.

Systems are Sociotechnical

These things, duration, MTTR, severity, they’re what John Allspaw and many of us now come to refer to as shallow metrics, because they obfuscate the messy details that are really informative about incidents. I wanted to just give one metaphor about that, which is probably pretty relevant to any of us who live in the western United States right now. Your systems are inherently complex, and trying to measure incident response for those systems by things like duration or MTTR is like assessing how teams are fighting wildfires in the western U.S. by counting the number of fires, or how long it takes them to put them out, versus understanding what’s happening for the teams on the ground in their reality, and each one is so remarkably different. That’s not the answer you want. I understand. If it’s not MTTR, don’t panic. If it’s not MTTR, then what is it? The answer to this, from my perspective is incident analysis. You’re going to get really mad at me and you’re going to scream, that’s not a metric. No, it’s not. It is the best thing to tell you about the resilience and the reliability of your systems.

What do those kinds of things look like? What kinds of data do you get out of incident analyses? I know we think data is numbers, and observability, and what comes out of Grafana. We have these expectations about what that looks like. There are numbers and metrics you can still get out of these kinds of approaches to studying your systems. Your systems are sociotechnical. They are a combination of humans and computers and what we expect them to do, which means you need to collect sociotechnical data. Some of the things that I pulled together here for you to think about are cost of coordination, how many people were involved? Were they paged overnight? Did they have to wake up in the middle of the night to deal with this? Across how many unique teams were there? How many people were there involved. PR and comms, did they have to get involved? How many tools, how many channels? There are so many things that tell you whether any given incident has a big internal impact, along with what you believe the external impact is, and how well your teams are dealing with those or how much your organization has to throw at something in order to deal with it.

Study near misses. How many near misses do you have compared to how many incidents you have? It’s way more, which means your success to failure ratio is way higher than you realize it is. They tell you things that you don’t get from metrics like duration, or MTTR. Then there’s other really interesting side effects of investing in incident analysis, and that’s, how much do people start to invest and participate in these things? How many people are reading these? You can totally track that and don’t be creepy about it. The number of people who are actually showing up to these kinds of post-incident reviews and attending to hear what’s happening? Are these things getting shared? Where else do they show up? Do they get referenced in PRs? Do they get referenced in code reviews? There’s all kinds of places, and you can put a number on any of these if you really need to put a number on a slide for somebody higher up the chain.

I want to talk a little bit more about the near misses piece of that, which is that near misses are successes. When you look at the write-ups from these few near misses, we have almost none, less than a percent by a long shot of these in the VOID. They talk about the kinds of things they find in near misses that they don’t even find in incident reviews. These are rich sources of data about where pockets of adaptation exist in your organization or on your team. Carl Macrae has this really great book called “Close Calls” where he talks about near misses as providing the source materials to interrogate the unknown. You can test assumptions and validate expectations, and become aware of ignorance and also watch experience as it plays out in your organization. They also highlight where people leverage their expertise and provide adaptive capacity when their system behaves in unanticipated or expected ways, which is what incidents are. They often include much richer information about sociotechnical systems, including things like gaps in knowledge, and breakdowns in communication, and even things like cultural or political forces on your systems.

Methods of Analyses in the VOID (Root Cause)

I want to talk next about one other thing that we track in the VOID so far, which is the methods of analyses that people use. We are really interested in the use of root cause analysis, or RCA. I’ll talk about why. Last year, we saw about a 26% rate of organizations either formally stating they use root cause analysis or have some root cause identified in their reports. That number went way down this year. I just want to clarify, we went from about 2,000 incidents to about 10,000 incidents, so the denominator changed. That 6% number, we didn’t see across the same set of report. I want to be really clear here. We’re beginning to build up this corpus in the VOID. That’s a spurious result. I want to talk about why we care about root cause and some interesting developments that have happened since the last VOID report. A very formal root cause analysis posits that an incident has a single specific cause or trigger, without which it wouldn’t have happened. It’s very linear. Once the trigger is discovered, a solution flows from it, the organization can take steps to ensure it never happens again. This linear sequence of events mindset, which is also known as the domino model, has its origins in industrial accident theory. We’ve adopted it, we’ve taken that on. Because we don’t go looking for them until after the fact, the reality is we don’t find causes, we construct them. How you construct them and from what evidence depends on where you look, what you look for, who you talk to, who you’ve seen before, and likely who you work for.

A funny thing happened between the last report and this one, because we had two really big companies last year in the VOID, that were doing root cause analysis, it was Google and Microsoft, we added Atlassian this year, which kept the number at least a little bit higher. Between that last report and June of this year, Microsoft stopped doing root cause analysis. I think that’s fascinating, because if an organization the size of Microsoft Azure, a very large organization, can change their mindset and their approach to it, any of us can. Any of us can change our mindset and our approach to any of the ways that we think about and look at how incidents inform us about our organizations. I think language matters. Microsoft realized that. They realized that when you identify a number of contributing factors, especially if they’re sociotechnical in nature, then you’re modeling a very different approach for how your team thinks about the systems it deals with. If you go and read these new reports, they call them post-incident reports, PIRs, because we all still need an acronym. They’re very different too, like the detail in those reports, the approach, the way of thinking about their systems has shifted. I’m not saying just because Microsoft Azure team suddenly said, we’re not going to do root cause, those were all a piece of the way they chose to change their approach. I just have to say, if Microsoft can do it, so can you.

We need a new approach to how we think about, analyze, talk about, and study incidents, and how we share the information from those. The biggest piece of that is to treat incidents as an opportunity to learn, not to feel shame or blame. I am so excited to see so many more companies sharing their incidents, and not seeing that as a place where PR or marketing has to run around and worry. They also favor in-depth analysis over shallow metrics. We’re going to move past MTTR, and worrying about duration and severity, and we’re going to dive into what’s happening. We’re going to listen to the stories of the practitioners who are at the sharp end, who are close to how these systems work. We’re going to use that to better understand those systems. We’re going to treat those practitioners and those people as solutions, not problems, and study what goes right, along with what goes wrong. This new approach, I suspect has a competitive advantage. I do believe that companies that do this will be more responsive in ways and have adaptive capacity that others don’t, which will give them an advantage over companies who don’t view the world this way.

Resources

I would like to encourage you to analyze your incidents. There’s a couple of resources in here for thinking about how to do that. I would love for you to submit them to the VOID. There’s a forum, handy-dandy forum, if you don’t have a lot, if you have a lot, you can get in touch and we’ll help you get those in there. You can actually become a member and participate in a variety of more involved ways if you’re so interested. Some of these data I referred back to the previous report from last year, a bunch of the things I talked about plus a bunch more will actually be in the next report which is coming soon.

Questions and Answers

Rosenthal: You mentioned that there’s another VOID report coming out soon, do you have a date now?

Nash: I do. The world is working in my favor now. It will be coming out on the 13th. People can go to the VOID website, and there’ll be a handy-dandy big button to go and download the report.

Rosenthal: You basically made a case in your presentation that there’s no metric that you can use to communicate the reliability or resilience of a site or an application. Is there a way that you could create a combined metric to distill down like one number or something that you could use to represent the resilience or reliability of your site or application?

Nash: No. I wish. Wouldn’t that be magical, and wouldn’t we all want to have that number and collect that number, and celebrate that number? Unfortunately, no, we have to do the hard work of digging into these things.

Rosenthal: You mentioned that you replicated the Monte Carlo simulation that somebody at Google did. Can you say a little bit more about how you replicated that? Did you have a team doing that? What’s involved there?

Nash: Yes, we did. First of all, it involved somebody else who writes better R code than I do. We actually had an intern from the University of British Columbia, whose name is William Wu. He actually helped us with this. He’s getting his PhD in evolutionary ecology, studies large, complex biological systems, which is really cool. He was really interested in how our complex sociotechnical systems work. What we did was we took all of those incident data and put them into two groups. You’re able to then run experiments on that, like A/B tests. It doesn’t take a lot of people to do this. I had one person who wrote some really great code, and that allowed us to really poke around a lot, too. We looked a lot at the distributions. He tried to fit power laws to things. Once we had all these data, we were able to separate them into different groups, and then test all these theories on them but, unfortunately, quite a few of them fell apart.

Rosenthal: You mentioned that Microsoft no longer does RCA at least with the Azure one.

Nash: The Azure health status page for all their various services, yes.

Rosenthal: If I work at a company that isn’t Microsoft Azure, what would be the one thing that you would recommend for me to improve my availability process, not MTTR? If I could only change one thing, would it be, stop doing RCA or something else?

Nash: This is one where I say language matters. Even if you are doing what your team officially calls RCA, what you really want to be able to do is have someone or someone’s people who have the dedicated skill set to dig into these kinds of incidents. I’ve seen people be able to do this work in environments where the belief is still that you can find one cause. We’re seeing a trend of people hiring incident analysts or taking folks who have been on the SRE team or whatnot. The skill set to invest in investigating your incidents is very different than the skill set it takes to build and run these systems. If I were to do one thing I would invest in a person or a team of people who are skilled at investigating incidents and distributing that information back out to the organization so people can learn from it. That skill set developed within the Azure team, and that led to a greater awareness of that. I think the change in the mindset there came from the investment in people and really taking a different approach to learning from incidents. Then eventually, they said, now we’re doing this other thing. We can call it this other thing and we’ll see what the world thinks of that. They actually asked for feedback on it, which I think is fascinating. The one thing is to have people who are really good at investigating incidents.

Rosenthal: What are your thoughts about the correction of errors approach that Amazon uses? Do you have any thoughts about that, as it relates to RCA?

Nash: When you investigate an incident, you’re not correcting errors. You’re learning about how your systems work. Along the way, you might fix some technical things, you hopefully change some sociotechnical things. I think that language has a similar mindset to it, that RCA does. Like, we’ll correct the errors, and errors corrected. What were those errors? I think it’s a very narrow view that the language reflects.

Rosenthal: It includes 5 why’s, and action items, and other stuff that’s been demonstrated in other forms don’t necessarily improve the reliability of a system, although they do keep us busy.

What are your thoughts on business perceived reliability versus having incident data?

Nash: I used this phrase in the talk, and it’s a safety science term. It’s maybe a bit obtuse. We talk about people at the sharp end, and then the blunt end, it’s a wedge. The people at the sharp end have a typically different perception and understanding of the reliability of their systems than the people at the more blunt and further removed or business end. There’s often a big disconnect between those two. I talk to a lot of SRE folks. I talk to a lot of just people running these types of systems who are often very frustrated at the lack of understanding at the business side of things. Ideally, some SRE practices aim to connect those a little bit better, trying to use things like SLOs which are designed in theory to align the performance of your system with the expectations of its customers, whatever those may be, like internal customers or whatnot. It’s usually pretty disconnected. The interesting thing about companies that really invest in that detailed incident analysis, is it reveals that reality, if you can do the work to push that information further back into your organization.

My favorite example of this is David Lee at IBM. He’s in the office of the CIO, a gigantic organization within a gigantic organization. IBM is huge. The office of the CIO is I think, ultimately, like 12,000 people. He’s managed to take in incident analysis and review process and create an environment where executives show up to these learning from incident reviews, I think they’re monthly. He’s actually tracking some of those data that I talked about, about how many people are coming to the meetings, how many people are reading the reports, and all of that? He’s watching that gain traction within the CIO organization. He’s taking the data from the sharp end and he’s bringing it into the business, and they’re beginning to see what the reality on the ground is. It reminds me of the early days of DevOps, where we’re trying to connect these two sides of the organization. I still see so much power in building a culture around these incident analyses, they reveal so much that typically at a certain distance from that on the business side of the house is rarely seen. There’s a gap there that people have to bridge. There’s work to be done to get those two groups aligned.

Rosenthal: You mentioned two ways not to do it. You outlined a little bit better process to investing in incident analysis. I’m going to post the Howie document, which is one company’s take on a better process for incident analysis.

Nash: The best process is the one that you come up with, for your own organization. There’s not a template. There’s not a forum. That’s very frustrating too. I’ve watched this happen in quite a few organizations where you just start doing this, and a process that you develop if you’re invested in this, in learning from incidents, it will be the one that you evolve and refine and change to work for your company. That is the take of one company that’s very good at this. That doesn’t mean that has to be exactly how you do it either. You just have to start.

See more presentations with transcripts

MMS • Ben Linders

Accountability in big tech companies seems to be lacking; it’s rare for people in senior positions to be held accountable. Engineers should be conscious of the culture they want to work in and watch out for their well-being, whereas companies should invest in their leaders to support people’s best work. Andy Walker gave a talk about how big tech lost its way at QCon London 2023.

As the company matures, accountability at the very top seems to disappear at the same time as accountability at entry levels gets ramped up, Walker said. It’s perfectly possible to imagine that the layoffs across tech are a way of getting rid of people that the leaders of those companies don’t want there. Yet, at the same time, we see executive pay going through the roof and it’s incredibly rare for someone in a position of seniority in big tech (we are talking director and above level) being held to account for bad behaviour, Walker explained:

For example, Sundar Pichai getting a pay deal of over $200 million dollars while firing 12,000 people and saying he had no choice because he had over-hired seems like rewarding failure at the top. While, at the same time, the 12,000 people who lost their jobs through no fault of their own had to enter what is now a very crowded job market.

As engineers we need to be really conscious about the culture we want to work in, Walker argued:

One of the things I’ve told a lot of people affected by layoffs recently is that you are not the company you work for. If you work in tech you’re going to have opportunities elsewhere.

Staying somewhere where you feel unable to make a positive difference isn’t going to help your mental well-being later on, Walker mentioned. Not only are you not your job, but your first priority is to look after your own wellbeing.

The sad thing is that when your company culture has died then it requires someone coming in at the very top to reboot it – there may not be much you can do, Walker said. You can see something along those lines happening at Microsoft right now with Satya Nadella though even they have blindly followed the mass firing playbook from Twitter, he mentioned. What you can do, before that happens, is to reinforce your culture with everyone who walks through the door. You are unlikely to be able to prevent the corporatisation of your workplace, but you can slow it down, he said. Investment in culture is an ongoing activity. If you don’t then your culture becomes something that happens to you, rather than a conscious choice on your part.

Walker suggested that companies should invest in their leaders. Leaders are either a floor to support people’s best work or a ceiling that limits it. When you become a director or a VP, your job has changed, he concluded. Leadership is not about having the answers – it’s about framing the problems that are worth solving and providing an environment in which they can be solved. Warning signs to watch out for are when leaders are providing solutions rather than defining outcomes and when they start talking about “holding people to account”. Both of these are about compliance rather than innovation.

InfoQ interviewed Andy Walker about how big tech measures success and what can be done to reverse the trends in the industry.

InfoQ: How does big tech measure success? What impact does this have?

Andy Walker: When you measure success by growth you run into Goodhart’s Law in a bad way. Goodhart’s Law can be summarised as “when a measure becomes a target then it ceases to be a good measure”. If you look at the way Big Tech reports growth, it’s in active users (and in some cases engagement). If you look at the problems with accountability-free freedom of speech then you should be able to spot a problem immediately. Every user that a tech company blocks is a user they aren’t monetising and something which hurts their growth story.

This is particularly true for people with polarising or extreme viewpoints. Investing in user safety becomes something that is done under duress. It’s not possible to ever get to zero abuse, but Big Tech sees funding this as a cost centre and something that will harm growth. Therefore, it frequently gets deprioritised as opposed to things which will bring growth.

InfoQ: What can companies do to reverse the negative trends in the industry?

Walker: Companies need to be really specific in supporting people through these changes and setting clear expectations for their leaders. They need to have checks and balances in place so that people in senior positions are held to account before they can do real harm.

They need to stop rewarding cargo crating and empire building as a means for career progression and reward impact which is achieved responsibly. They need to reward people who are on the side of their users rather than those on the side of their shareholders. To take either view is bad for the company, and truly effective leaders are able to balance the two conflicting needs.

MMS • RSS

Rhumbline Advisers lifted its holdings in MongoDB, Inc. (NASDAQ:MDB – Free Report) by 6.7% during the 1st quarter, according to the company in its most recent Form 13F filing with the SEC. The firm owned 80,846 shares of the company’s stock after buying an additional 5,060 shares during the quarter. Rhumbline Advisers owned approximately 0.12% of MongoDB worth $18,847,000 at the end of the most recent quarter.

Rhumbline Advisers lifted its holdings in MongoDB, Inc. (NASDAQ:MDB – Free Report) by 6.7% during the 1st quarter, according to the company in its most recent Form 13F filing with the SEC. The firm owned 80,846 shares of the company’s stock after buying an additional 5,060 shares during the quarter. Rhumbline Advisers owned approximately 0.12% of MongoDB worth $18,847,000 at the end of the most recent quarter.

Several other hedge funds and other institutional investors have also recently modified their holdings of MDB. Cherry Creek Investment Advisors Inc. increased its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 1.5% in the 4th quarter. Cherry Creek Investment Advisors Inc. now owns 3,283 shares of the company’s stock valued at $646,000 after acquiring an additional 50 shares during the period. CWM LLC increased its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 2.4% in the 1st quarter. CWM LLC now owns 2,235 shares of the company’s stock valued at $521,000 after acquiring an additional 52 shares during the period. Cetera Advisor Networks LLC increased its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 7.4% in the 2nd quarter. Cetera Advisor Networks LLC now owns 860 shares of the company’s stock valued at $223,000 after acquiring an additional 59 shares during the period. First Republic Investment Management Inc. increased its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 1.0% in the 4th quarter. First Republic Investment Management Inc. now owns 6,406 shares of the company’s stock valued at $1,261,000 after acquiring an additional 61 shares during the period. Finally, Janney Montgomery Scott LLC increased its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 4.5% in the 4th quarter. Janney Montgomery Scott LLC now owns 1,512 shares of the company’s stock valued at $298,000 after acquiring an additional 65 shares during the period. 88.89% of the stock is currently owned by hedge funds and other institutional investors.

Analyst Upgrades and Downgrades

A number of analysts have recently weighed in on MDB shares. Royal Bank of Canada raised their price objective on MongoDB from $400.00 to $445.00 in a research report on Friday, June 23rd. JMP Securities raised their price objective on MongoDB from $400.00 to $425.00 and gave the stock an “outperform” rating in a research report on Monday, July 24th. VNET Group reissued a “maintains” rating on shares of MongoDB in a research report on Monday, June 26th. Barclays raised their price objective on MongoDB from $374.00 to $421.00 in a research report on Monday, June 26th. Finally, KeyCorp raised their price objective on MongoDB from $372.00 to $462.00 and gave the stock an “overweight” rating in a research report on Friday, July 21st. One analyst has rated the stock with a sell rating, three have assigned a hold rating and twenty have assigned a buy rating to the company. Based on data from MarketBeat.com, the company has a consensus rating of “Moderate Buy” and a consensus target price of $379.23.

Check Out Our Latest Report on MDB

Insider Activity at MongoDB

In related news, CTO Mark Porter sold 2,669 shares of MongoDB stock in a transaction dated Friday, June 2nd. The stock was sold at an average price of $381.12, for a total value of $1,017,209.28. Following the completion of the transaction, the chief technology officer now owns 37,667 shares in the company, valued at approximately $14,355,647.04. The sale was disclosed in a document filed with the SEC, which is available through the SEC website. In other MongoDB news, CTO Mark Porter sold 2,669 shares of the business’s stock in a transaction that occurred on Friday, June 2nd. The stock was sold at an average price of $381.12, for a total transaction of $1,017,209.28. Following the completion of the sale, the chief technology officer now directly owns 37,667 shares in the company, valued at approximately $14,355,647.04. The transaction was disclosed in a document filed with the SEC, which is available through this link. Also, CRO Cedric Pech sold 360 shares of the business’s stock in a transaction that occurred on Monday, July 3rd. The stock was sold at an average price of $406.79, for a total value of $146,444.40. Following the sale, the executive now owns 37,156 shares of the company’s stock, valued at $15,114,689.24. The disclosure for this sale can be found here. Insiders sold a total of 79,220 shares of company stock worth $32,161,151 in the last 90 days. Corporate insiders own 4.80% of the company’s stock.

MongoDB Price Performance

Shares of MongoDB stock opened at $375.52 on Thursday. The company has a quick ratio of 4.19, a current ratio of 4.19 and a debt-to-equity ratio of 1.44. MongoDB, Inc. has a twelve month low of $135.15 and a twelve month high of $439.00. The business has a 50-day moving average price of $390.07 and a 200 day moving average price of $302.31. The firm has a market cap of $26.50 billion, a PE ratio of -80.41 and a beta of 1.13.

MongoDB (NASDAQ:MDB – Get Free Report) last announced its quarterly earnings results on Thursday, June 1st. The company reported $0.56 earnings per share for the quarter, beating the consensus estimate of $0.18 by $0.38. MongoDB had a negative return on equity of 43.25% and a negative net margin of 23.58%. The firm had revenue of $368.28 million during the quarter, compared to analyst estimates of $347.77 million. During the same quarter in the previous year, the business earned ($1.15) EPS. MongoDB’s revenue for the quarter was up 29.0% compared to the same quarter last year. Sell-side analysts predict that MongoDB, Inc. will post -2.8 earnings per share for the current fiscal year.

MongoDB Company Profile

MongoDB, Inc provides general purpose database platform worldwide. The company offers MongoDB Atlas, a hosted multi-cloud database-as-a-service solution; MongoDB Enterprise Advanced, a commercial database server for enterprise customers to run in the cloud, on-premise, or in a hybrid environment; and Community Server, a free-to-download version of its database, which includes the functionality that developers need to get started with MongoDB.

Featured Articles

Want to see what other hedge funds are holding MDB? Visit HoldingsChannel.com to get the latest 13F filings and insider trades for MongoDB, Inc. (NASDAQ:MDB – Free Report).

Receive News & Ratings for MongoDB Daily – Enter your email address below to receive a concise daily summary of the latest news and analysts’ ratings for MongoDB and related companies with MarketBeat.com’s FREE daily email newsletter.

MMS • Steef-Jan Wiggers

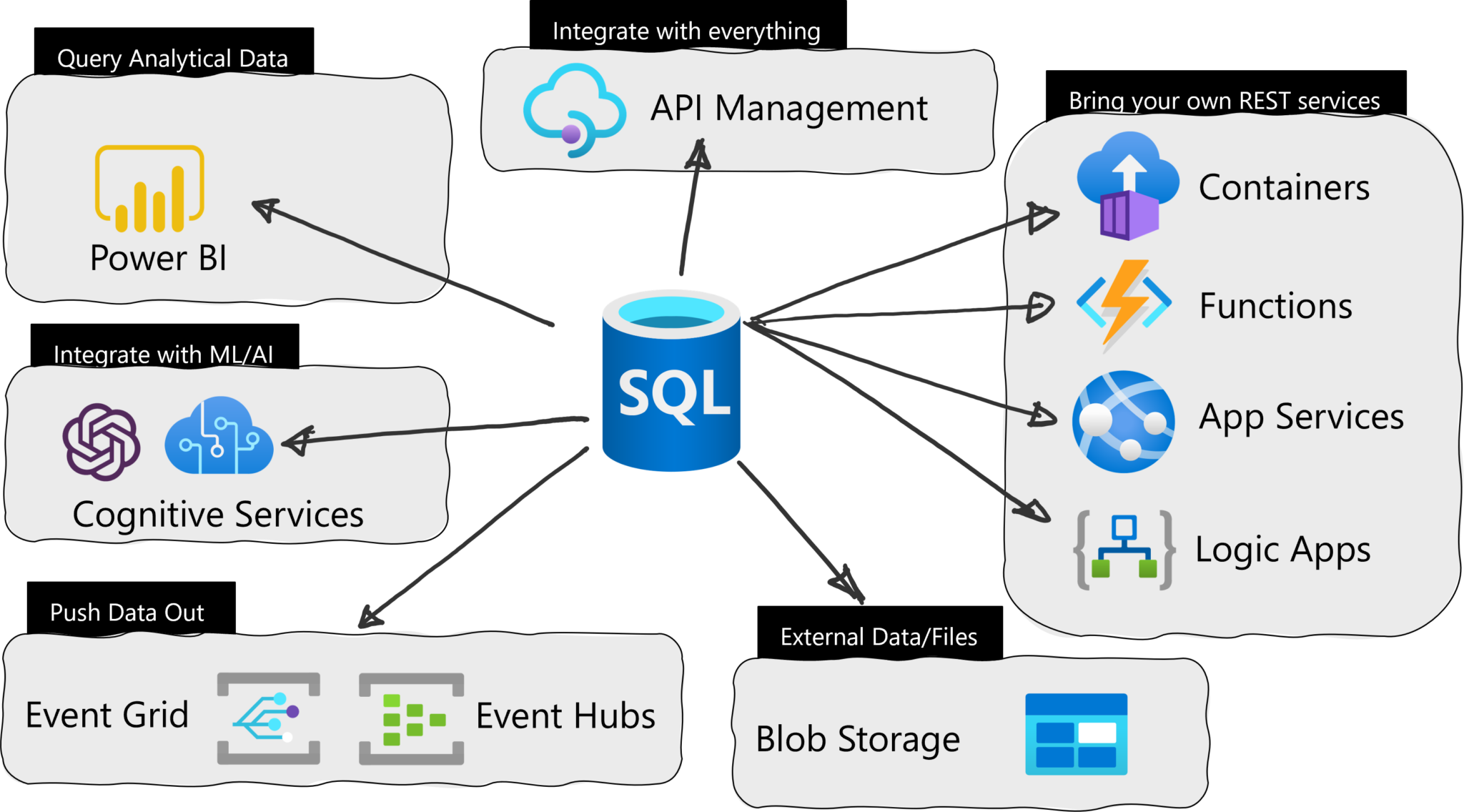

Microsoft recently announced the general availability (GA) of Azure SQL Database External REST Endpoint Integration – an ability to call a REST endpoint natively from Azure SQL Database.

Earlier, the company released a public preview of the Azure SQL Database feature that provides system-stored procedure sp_invoke_external_rest_endpoint, which invokes an HTTPS REST endpoint provided as an input argument to the procedure. It allows developers to call REST/GraphQL endpoints from other Azure Services from right in the Azure SQL Database. With the GA, the company enabled access to OpenAI, Azure Blob Storage, Azure Files, Azure Queue Services, and Azure Table Services. In addition, the feature also supports header and managed identity authentication, removing the option of passing passwords.

In an Azure Developer blog post, Brian Spendolini, a senior product manager of Azure SQL Database, provides an example of asking ChatGPT, “Why is the sky blue?” in a T-SQL statement that looks like this:

declare @url nvarchar(4000) =

N'https://openaidemo1.openai.azure.com/openai/deployments/talk-to-me-goose/chat/completions?api-version=2023-03-15-preview';

declare @headers nvarchar(102) = N'{"api-key":"12345,678910,1112"}'

declare @payload nvarchar(max) = N'{"messages":[{"role":"system","content":"Why is the sky blue?"}]}'

declare int, @response nvarchar(max);

exec = sp_invoke_external_rest_endpoint

@url = @url,

@method = 'POST',

@headers = @headers,

@payload = @payload,

@timeout = 230,

@response = @response output;

select as ReturnCode, @response as Response;

Furthermore, Spendoli outlines several use cases for the feature, such as:

- Activate workflows by sending an email using Azure Logic Apps

- For cache invalidation or update by calling an Azure Function

- Call a Durable Function to kick off some complex process

Overview of leveraging the External REST Endpoint Invocation feature in SQL Azure (Source: Microsoft Developer blog post)

With various possible use cases with the feature, the concept of calling a rest endpoint from a database is not new. For instance, in Oracle databases, it is available for some time, like in version 11g XE:

create or replace

procedure publish_cinema_event

( p_room_id in varchar2

, p_party_size in number

) is

req utl_http.req;

res utl_http.resp;

url varchar2(4000) := 'http://localhost:9002/cinema';

name varchar2(4000);

buffer varchar2(4000);

content varchar2(4000) := '{"room":"'||p_room_id||'", "partySize":"'||p_party_Size||'"}';

begin

req := utl_http.begin_request(url, 'POST',' HTTP/1.1');

utl_http.set_header(req, 'user-agent', 'mozilla/4.0');

utl_http.set_header(req, 'content-type', 'application/json');

utl_http.set_header(req, 'Content-Length', length(content));

utl_http.write_text(req, content);

res := utl_http.get_response(req);

-- process the response from the HTTP call

begin

loop

utl_http.read_line(res, buffer);

dbms_output.put_line(buffer);

end loop;

utl_http.end_response(res);

exception

when utl_http.end_of_body

then

utl_http.end_response(res);

end;

end publish_cinema_event;

For developers, the feature brings new options to build data integrations. In a Data Exposed episode, “Calling a REST service from Azure SQL DB,” Davide Mauri, principal product manager – Azure SQL DB at Microsoft, concluded:

You can have really full integration from Azure SQL with everything in just one line of code, which makes developers super-efficient.

In addition, in a tech community blog post on the feature, @gmedlin commented in the comment section:

This is awesome! SendGrid for Azure would be my top choice for External REST Endpoint Invocation. With that, we wouldn’t have to call a function or logic app to send emails.

With the company responding:

Thanks for the comment, @gmedlin, we will be sure to take a look at that. We are looking at enabling Azure Communication Services soon as well.

Lastly, more examples of leveraging the External REST Endpoint Invocation feature of SQL Azure are available in a GitHub repo.

OpenSSF New Manifesto Urges the Software Industry to Take Responsibility for Open Source Security

MMS • Sergio De Simone

The Open Source Consumption Manifesto from OpenSSF aims to make the software industry more aware of its responsibility when it comes to ensuring the software supply chain remains secure and healthy.

The importance of open source software today cannot be overstated and its contribution to efficiency and innovation has been tremendous. But, as recent vulnerabilities and attacks show, including Log4j and Log4Shell, open source security is still an open issue and there is no unity about how to best achieve it.

Some believe the education of software development teams should be a priority. Others focus on the value of frameworks, best practices, and standards. […] any of the above are workable methods.

This is where the OSCM comes in, trying to build a consensus on a simple approach. As a first step, the manifesto attempts to bring the focus on “consumption”, as a more general frame than “development”, with security vulnerabilities being only a part of the equation. The other part of the equation lies deep within the software supply chain, where new kind of attacks have become commonplace.

Open source consumption risk now includes malicious packages and malware attacks. In quick order, bad actors have shifted left to target open source projects. Attacks like dependency and manifest confusion represent real risks.

The OSCM includes a number of points attempting to bring the attention to and prioritize what really matters. For example, it stresses the fact that not all vulnerabilities are actively curated and scoring systems such as CVSS may suffer from a lag effect.

It also suggests using audit and quarantine functionality for components matching known vulnerabilities and malicious packages as well as focusing on tools and processes allowing teams to take informed decisions on open source software they are using.

Two additional suggestions, among several others, include actively engaging with open source developers to contribute to their effort and adopting tooling, best practices, and processes aimed to improve security.

The Open Source Consumption Manifesto is still in its early days and setting itself as a collaborative endeavor open to contributions and aiming for inclusion. It is hosted on GitHub and its proponents are welcoming pull requests.