National Pension Service reduced its stake in shares of MongoDB, Inc. (NASDAQ:MDB – Free Report) by 1.4% during the 3rd quarter, according to its most recent Form 13F filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The fund owned 131,005 shares of the company’s stock after selling 1,810 shares during the quarter. National Pension Service owned about 0.18% of MongoDB worth $35,417,000 at the end of the most recent quarter.

Several other hedge funds and other institutional investors also recently made changes to their positions in the company. MFA Wealth Advisors LLC bought a new stake in shares of MongoDB during the 2nd quarter valued at $25,000. J.Safra Asset Management Corp increased its holdings in MongoDB by 682.4% in the second quarter. J.Safra Asset Management Corp now owns 133 shares of the company’s stock valued at $33,000 after purchasing an additional 116 shares during the last quarter. Quarry LP boosted its holdings in MongoDB by 2,580.0% during the second quarter. Quarry LP now owns 134 shares of the company’s stock worth $33,000 after buying an additional 129 shares during the last quarter. Hantz Financial Services Inc. acquired a new position in shares of MongoDB during the 2nd quarter worth about $35,000. Finally, GAMMA Investing LLC raised its position in shares of MongoDB by 178.8% in the 3rd quarter. GAMMA Investing LLC now owns 145 shares of the company’s stock valued at $39,000 after acquiring an additional 93 shares during the period. 89.29% of the stock is owned by institutional investors and hedge funds.

Insiders Place Their Bets

In related news, Director Dwight A. Merriman sold 3,000 shares of the business’s stock in a transaction on Wednesday, October 2nd. The shares were sold at an average price of $256.25, for a total value of $768,750.00. Following the sale, the director now owns 1,131,006 shares of the company’s stock, valued at $289,820,287.50. The trade was a 0.00 % decrease in their ownership of the stock. The sale was disclosed in a document filed with the SEC, which is available through the SEC website. In other MongoDB news, Director Dwight A. Merriman sold 3,000 shares of the stock in a transaction dated Wednesday, October 2nd. The stock was sold at an average price of $256.25, for a total transaction of $768,750.00. Following the completion of the sale, the director now directly owns 1,131,006 shares in the company, valued at approximately $289,820,287.50. This trade represents a 0.00 % decrease in their position. The sale was disclosed in a legal filing with the SEC, which is accessible through this link. Also, Director Dwight A. Merriman sold 1,385 shares of the business’s stock in a transaction dated Tuesday, October 15th. The shares were sold at an average price of $287.82, for a total value of $398,630.70. Following the completion of the transaction, the director now directly owns 89,063 shares in the company, valued at $25,634,112.66. This represents a 0.00 % decrease in their ownership of the stock. The disclosure for this sale can be found here. Insiders sold a total of 24,281 shares of company stock valued at $6,657,121 in the last 90 days. Corporate insiders own 3.60% of the company’s stock.

Analyst Ratings Changes

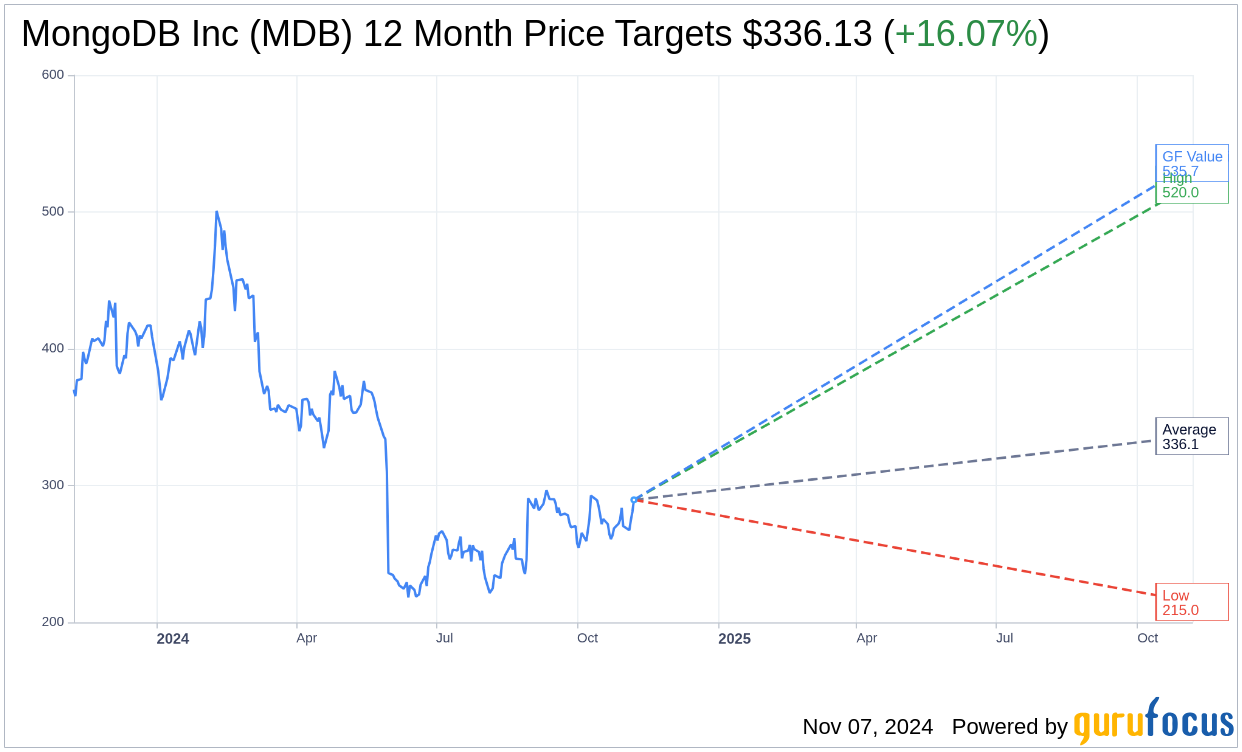

Several equities analysts recently issued reports on MDB shares. Sanford C. Bernstein boosted their price objective on MongoDB from $358.00 to $360.00 and gave the company an “outperform” rating in a research report on Friday, August 30th. Royal Bank of Canada reissued an “outperform” rating and issued a $350.00 price target on shares of MongoDB in a research note on Friday, August 30th. Tigress Financial dropped their target price on MongoDB from $500.00 to $400.00 and set a “buy” rating on the stock in a research report on Thursday, July 11th. JMP Securities reissued a “market outperform” rating and set a $380.00 price target on shares of MongoDB in a research report on Friday, August 30th. Finally, Oppenheimer increased their price objective on MongoDB from $300.00 to $350.00 and gave the company an “outperform” rating in a report on Friday, August 30th. One research analyst has rated the stock with a sell rating, five have issued a hold rating, twenty have assigned a buy rating and one has issued a strong buy rating to the company’s stock. Based on data from MarketBeat.com, the stock presently has a consensus rating of “Moderate Buy” and an average target price of $337.96.

View Our Latest Analysis on MDB

MongoDB Price Performance

Shares of MDB stock traded up $13.14 during trading hours on Thursday, reaching $294.12. The company’s stock had a trading volume of 1,190,901 shares, compared to its average volume of 1,429,840. The company has a quick ratio of 5.03, a current ratio of 5.03 and a debt-to-equity ratio of 0.84. MongoDB, Inc. has a fifty-two week low of $212.74 and a fifty-two week high of $509.62. The company has a market capitalization of $21.73 billion, a price-to-earnings ratio of -93.04 and a beta of 1.15. The firm’s 50 day simple moving average is $276.77 and its 200-day simple moving average is $277.95.

MongoDB (NASDAQ:MDB – Get Free Report) last issued its earnings results on Thursday, August 29th. The company reported $0.70 EPS for the quarter, topping the consensus estimate of $0.49 by $0.21. The firm had revenue of $478.11 million during the quarter, compared to the consensus estimate of $465.03 million. MongoDB had a negative return on equity of 15.06% and a negative net margin of 12.08%. The business’s quarterly revenue was up 12.8% on a year-over-year basis. During the same quarter in the previous year, the firm earned ($0.63) earnings per share. Sell-side analysts forecast that MongoDB, Inc. will post -2.39 earnings per share for the current year.

MongoDB Company Profile

(Free Report)

MongoDB, Inc, together with its subsidiaries, provides general purpose database platform worldwide. The company provides MongoDB Atlas, a hosted multi-cloud database-as-a-service solution; MongoDB Enterprise Advanced, a commercial database server for enterprise customers to run in the cloud, on-premises, or in a hybrid environment; and Community Server, a free-to-download version of its database, which includes the functionality that developers need to get started with MongoDB.

See Also

Before you consider MongoDB, you’ll want to hear this.

MarketBeat keeps track of Wall Street’s top-rated and best performing research analysts and the stocks they recommend to their clients on a daily basis. MarketBeat has identified the five stocks that top analysts are quietly whispering to their clients to buy now before the broader market catches on… and MongoDB wasn’t on the list.

While MongoDB currently has a “Moderate Buy” rating among analysts, top-rated analysts believe these five stocks are better buys.

View The Five Stocks Here

Which stocks are major institutional investors including hedge funds and endowments buying in today’s market? Click the link below and we’ll send you MarketBeat’s list of thirteen stocks that institutional investors are buying up as quickly as they can.

Get This Free Report