Month: July 2022

MMS • Renato Losio

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Google recently announced the general availability of Rocky Linux optimized for Google Cloud. The new images are customized variants of Rocky Linux, the open-source enterprise distribution compatible with Red Hat Enterprise.

Developed in collaboration with CIQ, the support and services partner of Rocky Linux, the new images are a direct replacement for CentOS workloads. Started by Gregory Kurtzer, the founder of the CentOS project and CEO of CIQ, Rocky Linux is a downstream, binary-compatible release built using the Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) source code. The distribution was born after Red Hat decided not to provide full updates and maintenance updates for CentOS 8 as initially announced.

Google Cloud builds and supports the Rocky Linux images for Compute Engine, with both a fully open source version and one optimized for Google Cloud: this version has the suffix “-optimized-gcp” and uses the latest version of the Google virtual network interface (gVNIC). Clark Kibler, senior product manager at Google, explains:

These new images contain customized variants of the Rocky Linux kernel and modules that optimize networking performance on Compute Engine infrastructure, while retaining bug-for-bug compatibility with Community Rocky Linux and Red Hat Enterprise Linux. The high bandwidth networking enabled by these customizations will be beneficial to virtually any workload, and are especially valuable for clustered workloads such as HPC (see this page for more details on configuring a VM with high bandwidth).

A few months ago, Venkat Gattamneni, senior product manager at Google, announced the partnership with CIQ and promised more integrations with the new distribution:

In addition to CIQ-backed support for Rocky Linux, Google is also working with CIQ to provide a streamlined product experience – with plans to include performance-tuned Rocky Linux images, out-of-the-box support for specialized Google infrastructure, tools to help support easy migration, and more.

Google Cloud is not the only provider supporting Rocky Linux. AWS and Azure are other sponsors of the Rocky Linux project and offer AMI in the AWS and Azure marketplaces. Kibler adds:

Going forward, we’ll collaborate with CIQ to publish both the community and Optimized for Google Cloud editions of Rocky Linux for every major release, and both sets of images will receive the latest kernel and security updates provided by CIQ and the Rocky Linux community.

The Rocky Linux 8 AMI optimized for Google Cloud is available for all x86-based Compute Engine VM families. Versions for the new Arm-based Tau T2A and Rocky Linux 9, the latest Rocky generally available release, are expected soon. Google does not charge a license fee for using Rocky Linux with Compute Engine.

A New Service from the Microsoft and Oracle Partnership: Oracle Database Service for Microsoft Azure

MMS • Steef-Jan Wiggers

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

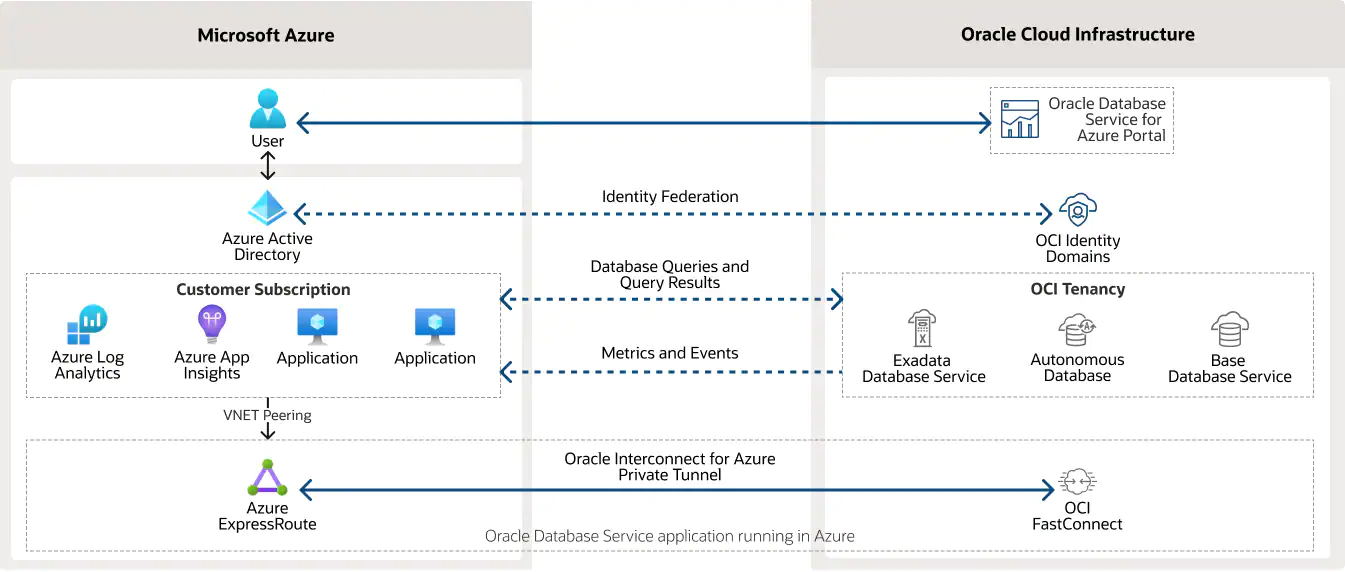

Recently, Microsoft and Oracle announced the general availability (GA) of Oracle Database Service for Microsoft Azure, a new service that allows Microsoft Azure customers to provision, access, and monitor enterprise-grade Oracle Database services in Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI).

Microsoft and Oracle have partnered since 2019 and first delivered the Oracle Interconnect for Microsoft Azure,, allowing hundreds of organizations to use secure and private interconnections in 11 global regions. Now both companies have extended their partnership with the GA release of Oracle Database Service for Microsoft Azure, which builds upon the core capabilities of the Oracle Interconnect for Azure and enables any customer to integrate workloads more easily on Microsoft Azure with Oracle Database services on OCI.

Through the Azure Portal, customers can deploy Oracle Database running on OCI with the Oracle Database Service. The service automatically configures everything required to link the two cloud environments and federates Azure Active Directory identities, making it easy for Azure customers to use the service. Furthermore, OCI database logs and metrics are integrated with Azure Services such as Azure Application Insights and Azure Log Analytics for simpler management and monitoring Azure Application Insights and Azure Log Analytics.

Source: https://www.oracle.com/cloud/azure/

Jane Zhu, senior vice president, and chief information officer, Corporate Operations, Veritas, said in a Microsoft press release:

Oracle Database Service for Microsoft Azure has simplified the use of a multi-cloud environment for data analytics. We were able to easily ingest large volumes of data hosted by Oracle Exadata Database Service on OCI to Azure Data Factory where we are using Azure Synapse for analysis.

In addition, Holger Mueller, principal analyst and vice president at Constellation Research Inc., told InfoQ:

It is remarkable as customers brought competitors together – and now Oracle is even better integrated into the Azure… practically making Oracle a first-grade citizen in Azure – operating the Oracle DB from an Azure console. This is how multi-cloud should be implemented – so customers win. And they must win……

Furthermore, he said:

Tacitly it is also the admission by Microsoft that the Oracle DB is better than MS SQL Server and by Oracle that Microsoft PowerBI is better than Oracle Analytics – at least for some customers… and Larry J Ellison is right – it is all about giving customers choices.

Lastly, there are no charges for using the Oracle Database Service for Microsoft Azure, the Oracle Interconnect for Microsoft Azure, or data egress or ingress when moving data between OCI and Azure. Customers will pay only for the other Azure or Oracle services they consume, such as Azure Synapse or Oracle Autonomous Database.

MMS • Ben Linders

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Empathy is the first step in practicing sustainable, genuine inclusion. If persons or groups of people feel unwelcome because of the language being used in a community, its products, or documentation, then the words can be changed. Identifying divisive language can help to make changes to the words that we use.

Eliane Pereira and Josip Vilicic, both technical writers, spoke about promoting inclusion in documentation at OOP 2022.

Empathy is a conscious practice where we listen to each other and try to feel what they are feeling, Vilicic said. This allows a person to relate to someone else’s experience, even if it’s unfamiliar.

Pereira mentioned that empathy is the key to understanding how others feel in certain situations, even if the situation does not impact you. A word can be just a word for you, but the same word can impact your coworkers and make the work environment unsafe for them.

It takes empathy and willingness to make changes so that everyone feels included, as Pereira explained:

For example, in the engineering field, master/slave is a model of asymmetric communication or control where one device or process, “master”, controls one or more other devices or processes, the “slaves”. For a descendant of slaves who decides to contribute to a project, the perceived racial connotations associated with the terms, invoking slavery, is terrible.

Vilicic mentioned that the most important thing is having support from the top decision-makers in an organization in improving the language. Once there is ideological support, the difficulty of the journey is less important, because we know we have a good goal in mind: improving the language so it doesn’t harm our community, he said.

By using inclusive language, we give everyone the opportunity to be themselves, Pereira argued. We can ensure that we are not using expressions that can be punitive, or make people feel rejected or embarrassed for what they are, she said.

InfoQ interviewed Eliane Pereira and Josip Vilicic about promoting empathy and inclusion in documentation.

InfoQ: What role does empathy play when it comes to inclusion?

Josip Vilicic: If someone says that they are being illegitimately excluded from a community, and the community says this is unintentional, there is a conflict.

Conflict is not inherently bad… but we can respond to conflict in a destructive (defensive or aggressive) manner, or in a constructive (empathetic) manner. If the community actively listens, does not deny the experience that the excluded group shares, and does not want to perpetuate harm, then the only choice left is for the community to fix the inequality through inclusion.

InfoQ: What can be done to encourage and support people in changing the language?

Eliane Pereira: Speak up to show that changes are needed. Listen if you think that some changes are not needed. People are used to the harmful language being present in their daily lives to the point that, when they are asked to change, they will say, “This has been here forever, we don’t need to change it, it is just a word”.

That is why we need to explain why we need those words to be replaced, so people can be aware that those are not just words, but a way to communicate something and sometimes, this something can be derogatory to someone.

InfoQ: How can the use of inclusive language increase psychological safety?

Vilicic: Using inclusive language signals to the audience that we are moving forward in a way that is sensitive, intentional, and kind. This can make teammates feel like they are in a supportive environment, where they can speak freely and they won’t be rejected.

No matter what our professional efforts are, we’re a group of imperfect people working towards a shared goal. When we base our interactions around respecting each other’s humanity, we allow each other to collaborate towards amazing things.

Pereira: Some words have a connotation for us, but for others, can be a pain point in their lives. For example, saying you have ADHD to express you are having difficulties concentrating in your work can make a colleague who actually has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to feel embarrassed or afraid that they are labelled as a worker with inability to perform their job. That is why we think that it is important to avoid metaphors in expressing yourself. Saying you are unable to concentrate on work on that day is clear enough.

MMS • Sergio De Simone

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Alibaba financial arm Ant Group has open sourced SecretFlow, its privacy-preserving framework, with a specific focus on data analysis and machine learning.

SecretFlow includes a number of components, such as a secure processing unit, which provides secure computation capabilities guaranteeing data privacy; a homomorphic encryption unit; a portable simplest oblivious transfer protocol implementation; and SecretFlow, a higher-level unified framework integrating all of them. While the high-level SecretFlow module is written in Python, the lower-level modules are written in C, C++, and assembly.

IMAGE

SecretFlow aims to be complete, transparent, open, and interoperable with other technologies. According to the Ant Group, the framework aims to make it easier for developer to create applications based on privacy-preserving computing and to contribute to the further growth of the market and technology maturity.

You can install SecretFlow by running pip install -U secretflow. The following snippet shows how you can generate a random number between 3 and 4 for a specific user in standalone mode:

import secretflow as sf

>>> sf.init(['alice', 'bob', 'carol'], num_cpus=8, log_to_driver=True)

>>> dev = sf.PYU('alice')

>>> import numpy as np

>>> data = dev(np.random.rand)(3, 4)

>>> data

SecretFlow can also be deployed in cluster mode, which enables allocating nodes to specific users to increase privacy. SecretFlow cluster mode is based on Ray, an open source framework that provides a simple, universal API for building distributed applications.

For a quick start with SecretFlow, you can check the tutorials which present a number of use cases, from data preprocessing to logistic regression, to neural network training, and so on.

Privacy-preserving computation is a technique that aims to provide protection for sensitive data while they are processed. Using such techniques, e.g., homomorphic encryption, you can carry through computation over encrypted data, which ensure it cannot be collected or tampered with during the processing.

MMS • Lilac Mohr

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Subscribe on:

Transcript

Shane Hastie: Good day, folks. This is Shane Hastie for the InfoQ Engineering Culture Podcast. Today I’m sitting down with Lilac Mohr. Lilac is an engineering leader at Pluralsight. Lilac, welcome. Thank you for taking the time to talk to us today.

Lilac Mohr: Thanks for having me, Shane.

Shane Hastie: Let’s start a little bit and who’s Lilac, what’s your background?

Introductions [00:25]

Lilac Mohr: As you said, right now I lead software engineering teams that are working on the Flow product at Pluralsight. Flow’s the software delivery intelligence platform. So we look at development workflows holistically. We look at all the different activities that make up an engineer’s day, how engineering teams collaborate, how well they’re doing unpredictability of being able to deliver on their commitments, and the general efficiency of the workflow.

And it’s really fun because we get to use our own product and continuously improve the product and the process. And prior to this job I led other engineering teams, but I was also a developer for a very long time. So I’m still very connected to the software engineering side.

Shane Hastie: What are some of the things that get in the way of engineers being productive today?

Challenges engineering teams are facing [01:20]

Lilac Mohr: We try to stay away from the word productivity, we don’t want to measure engineering productivity. We want to really have a holistic view. Make sure that we’re looking at engineers as people, at what makes their day good. At the end of the day ask them the question, “What were the blockers you had today? And then what were things you were really excited about today?”

And as an engineering leader, I do have to talk about deliverables, being able to deliver with excellence and the outcomes, but then it comes down to the people who are really behind the code. Every line of code comes from an engineer, and it comes from a collaborative process. And some of the things that I’ve found have been creating friction to that’s delivery. Right now I think with the Great Resignation it’s very difficult for me to keep a healthy team because people are leaving, so I think that’s where the culture plays in and it’s important. When someone leaves, it puts a big burden on everyone who’s left. So I want engineers to feel like they can keep moving forward and don’t have to take on a lot of extra work.

I think that’s a big challenge that all engineering teams are facing right now. And as something we do with our Flow product, is we’re always talking to our customers and trying to understand what it takes to have great engineering teams. We ask them the question, “Are your team set up for success?” And we get a wide variety of answers. It’s actually a difficult question to answer. A lot of times engineering managers focus on the process and the tools and say, “If I have the right tools, if I have an agile process, then my teams are set up for success.”

And that’s not digging deep enough, in my opinion. I think that a lot of times that’s based on an old playbook. Everyone is still talking about agile transformation as they have been the last 20 years. And with all the attrition that we’re seeing, you need to really focus on people. You need to take a broader view of everything that goes into making teams healthy.

Shane Hastie: What does a healthy team look like and feel like today?

What makes a healthy team [03:39]

Lilac Mohr: I think it comes down to developer satisfaction. And actually, I’m really big into metrics, and I think part of that is looking at the data itself, for how they’re able to deliver what their day looks like. But then part of it is also being able to survey them and ask them, “How are you doing? How are you feeling? What’s your confidence level right now?”

So I think it’s a combination of those factors. And I think a healthy team is a team that genuinely likes everyone on the team. They like working together, they like solving problems. They feel empowered to be able to make decisions that are closest to them, the engineers are the ones that are the closest to the code. And they want to feel that they understand the value of the things that they’re producing, and that they’re empowered to be able to make those decisions.

Shane Hastie: As an engineering leads, how can you influence this? How do you create this space?

Leaders enable the culture [04:43]

Lilac Mohr: It all comes down to culture. And I think that visibility is really important. I think that when you have the right metrics and you have the visibility into those metrics, then you let individuals make decisions about their team, what’s best for their team. And I think that drives the culture.

I think that it’s also important to have gratitude and have a culture of constantly acknowledging people’s hard work and their contributions. And not just coming from leadership, but encouraging them to acknowledge each other and have that space where you can provide feedback across teams, up, down, all around. It just becomes part of the culture. And the example of how we do this at Pluralsight and at Flow is we have Gratitude Fridays, where on Friday everyone posts the co-worker of the Week and recognizes someone who just moved the needle a little bit on making their experience that week fantastic. And it’s really fun to see everyone just acknowledging each other.

And I know, doing a skip level review with one of the new engineers, I remember him telling me, “At first I was really sceptical and thought it was really cheesy to do that. But then after someone tagged me and acknowledged me for the help that I provided that week, it felt really good, and I get it now.” I love hearing that type of feedback and seeing people just appreciate each other and enjoy working together as a team.

Shane Hastie: The perspective that you just mentioned from that engineer, “It felt really tacky,” it does kind of sound like that. As an organization, as a leader, as a co-worker, how do you prevent that from becoming tacky?

An example I can give is one organization that I spent some time with used a weekly 15-5, where they asked five questions, 15 minutes, “How are you doing?” And if anyone seemed even vaguely dissatisfied, a very senior leader, out of genuine care and concern, would immediately get hold of that person and say, “What’s going on? How can I help?” But to the engineers this felt intrusive and creepy. So they stopped reporting it was tough, everything was shiny, so they didn’t get the personal phone call.

Creating trust and enabling openness [07:18]

Lilac Mohr: Yeah, I think you have to create that trust in each other. And I think that a lot of those types of initiatives need to come from within, not from leaders saying, “Hey, this is the great new thing we’re going to do.” Maybe they can get it started and then make sure they have that feedback loop and that ear to the ground to ensure that it’s being carried on by the team members, that they appreciate it and that they share it with each other. And I think that’s important.

For example, like what you mentioned in one-on-ones. Everyone talks about how important it is to get that feedback in one-on-ones and how employees are doing, and making sure as a leader that you can address some of that’s discontent. But there’s ways to do it that are healthy, and I think there’s ways to do it that feel weaponizing. It’s about creating that safe environment. And being able to ask, if someone shares some information with you about how they’re doing, make sure that you ask them, “Is this okay if I share this with anyone else?” Sometimes you want to keep that relationship private.

I think as humans, when someone says that something’s wrong, you want to immediately react and say, “Well, I want to fix it.” Or you want to make them feel better. Sometimes all you need to do is just validate them and say, “What, if anything, would you like me to do about this? Or do you want me just to be a sounding board just to listen?” And sometimes people say, “Right now I just need you to listen.”

Shane Hastie: One of the things you mentioned earlier on, Lilac, was the importance of metrics and getting that feedback about what is actually happening in the team, the way work is flowing and so forth. Couple of things if I could explore with you there. One, what are some of those important metrics?

The importance of metrics [09:13]

Lilac Mohr: First I’d like to zoom out and just talk about the importance of metrics in general. I think a lot of times engineering leaders are very comfortable with using metrics to measure systems. We want to know how is the database operating, is the system up or down? Things that are less human. And then when they think about their humans they get a little bit uncomfortable about using metrics.

And I think that discomfort probably comes from focusing on a single metric. I think that the holistic approach is what you really need to take, where you’re not looking at just a single dimension. We all know that if you focus on a single metric, that’s what you’re going to get. And sometimes you are optimizing one little piece, but it actually creates tension somewhere else. Or maybe you’re focusing on the wrong thing. A lot of times that’s called the streetlight effect, where maybe you dropped your keys on the way to your car and the dark, but where you’re going to look is under the streetlight because that’s where you can see them.

Examples of metrics that can be useful [10:20]

Lilac Mohr: At Flow, we really try to create this holistic view, where we’re looking at engineering metrics down to the primary level is your code commits. So making sure that engineers have good habits around code, and those habits need to come with a purpose. The reason that we want to commit frequently is because we don’t want to hold onto code until it gets stale. We want to have that safety to check in the code and then be able to quickly get some peer review on it and get the process moving. We want to make sure that we’re freed up to code frequently. How frequently you commit code is not about how fast you’re working, it gives you an outlet as an engineer to say, “I don’t have time to do my work because I keep getting pulled in these different directions,” or, “I have meetings all day.” And it allows you to have those types of conversations with your leader.

That’s at the primary level, just things you should be doing is making the time to be able to code and doing frequent commits. And then the next level is collaboration, which I think is the most critical to code quality. A lot of times we think about code quality as lets have tools that analyze our code for that quality. But the quality really comes from helping each other on a team. Doing that peer review and doing it effectively, and being able to get all that work in progress moved through the system.

We take a look at pull requests, at the type of comments you’re getting on pull requests. How long they’re sitting in queues before another pair of eyes takes a look at them. And then also making sure that we’re not just rubber-stamping them as they go through. It’s a great way to learn and to help each other in that quality, so that’s the second level. And then the highest level that we track in Flow is at the ticket level, which is, these are the things that your team committed to doing in the sprint or in this chunk of time. Are you able to deliver on those, and what are the blockers to flow? Where is that work getting stuck in queues? Where are there unnecessary handoffs, anything else that we can improve in that higher level process.

I think all those things stack on top of each other and help you get an understanding of how, as a team, you’re able to deliver code. And important part of using those metrics is using them to guide discussions. They’re not supposed to be used to punish teams, to make teams feel bad about their process, to blame anyone. It’s all about being able to identify things that sometimes your intuition doesn’t realize that some of that friction is there. It gets conversations going. And I think that if it’s framed that way, then those metrics are enabling.

Shane Hastie: How do we ensure, and as a manager, how do I make sure that we’re not bringing that blame culture in, that we’re not using those metrics in the ways that would be so easy to do, but as you say, are not right.

Empowering people to own their own improvements [13:49]

Lilac Mohr: I think visibility is the key, in having access to the metrics. We have an engineer who was using Flow at her previous company. And she said that her leader would come in and show the Flow metrics to the team and provide some insight, but they didn’t have access to that data themselves. And she was curious, she was like, “Well, if they’re tracking this information about me, what else does he know? What else is in there?”

I think that what we’re trying to do with our customers is encourage them to let individual contributors have access to their own metrics. And we found that by doing that internally in our own team, a lot of great insights come out. Sometimes what we do is we just say, “Okay, just explore the metrics and come back with one thing. One thing that you found that’s interesting, maybe something unexpected, or something that you want to improve on as an individual or as a team.” And we’ve found amazing things come out of that because it’s open, it’s not coming from engineering managers. It’s not something punishing like, “I found this thing we can improve upon.” It’s asking them to be empowered, to look at their own data and make improvements.

Shane Hastie: One of the things you mentioned earlier on that I’d like to just delve into a little bit more again, if I may. You spoke about how team performance does come when people like each other and work effectively together. How do we prevent that from becoming a monoculture?

Avoiding monoculture [15:28]

Lilac Mohr: I think that’s an important topic. And a lot of times we find our teams do have a subculture. The teams, we let them pick their own names and they’re really proud of who they are. And I think that probably needs to be balanced with the culture for the entire engineering organization, because one of the problems is a lot of times it creates problems with inclusion. For example, an engineer who maybe is older, who’s on a team with younger individuals, they talk about different things. And I’ve heard some of this feedback. They talk about things that he feels he can’t relate to. So how do we create that sense of inclusion on a team and still allow them to feel really close to each other [inaudible 00:16:18]?

Pluralsight does really well because we talk about inclusion and diversity a lot. We just make it … It’s not a special topic we discuss, it’s just part of how we think. So we’re constantly asking, “Am I being inclusive?” And being able to stand up for each other and be able to provide that feedback and say, “I feel that this person was left out of the conversation,” or, “Can we choose an activity that might be more inclusive to do as a group?” And by talking about it a lot it makes it safe. And it makes it something that, when it’s not calling people out, it’s just pointing out something that we all are aiming towards. We all want everyone to feel good.

And I know that personally, as a female software engineer in a very male-dominated industry, I’ve been doing this for about 25 years. So back in the late ’90s, a lot of times I was at startups where I was the only female. Sometimes the only female engineer, sometimes the only female in the entire small organization. And there were a lot of awkward situations where I didn’t feel like I belonged. And coming into Pluralsight and being able to say, “I belong here” was really powerful for me. Because looking back, I didn’t always have that feeling. And I think it comes from just creating the importance around belonging, where everyone really wants everyone else to feel like they should be here. And it’s huge.

Shane Hastie: One of the things that we see, and I’d love to know your experiences around this, becoming an engineering leader, we often take the best technologist and we throw them into a leadership position. And one statistic says 58% of new managers receive absolutely no training.

How do we help people who are transitioning into those leadership roles become leaders? Because the skillsets are very, very different from the individual contributor to the leader.

Helping new leaders [18:30]

Lilac Mohr: It’s definitely a challenge. I know in the Flow organization, we do have that culture of taking the best engineer and saying, “You’re going to be the leader,” and it doesn’t always work out. A lot of times we have seen those leaders go back to being individual contributors. And we make it okay, we make it okay even within the organization to do that because otherwise they would leave the organization to become ICs.

But part of it is making sure that they get the satisfaction that they did from being able to generate a lot of code to help their team, to be able to focus on other high-performing engineers and be able to raise the level up of the entire organization. I think it’s just that mind shift. It’s very difficult to let go off code because we enjoy writing code, but how can you be more impactful? Instead of just grabbing tickets and then becoming a bottleneck for your team, how can you coach others to be able to get to the next level with our own careers?

And then also, how can you keep your fingernails dirty in the code, because that’s what you love. Maybe doing some pairing with engineers to help them get their own levels up or be able to be involved in architectural discussions. Ways that you can still help at a technical level, but you’re helping not just in the code, but helping the team move up and improve their own career paths and being able to deliver.

Shane Hastie: In your position as an even more senior leader, what are you doing?

Transitioning into more senior leadership [20:14]

Lilac Mohr: For me, the transition from individual contributor to a leader of one team, to a leader of multiple teams, it was tricky because you’re responsible for more. You know that ultimately, I’m responsible for all these outcomes, but I have to resist the urge to micromanage. I have to trust people.

I think that I would focus that effort where I want to dig in and be able to know everything that’s going on, to focus on coaching and focus on that higher level of enabling people and putting that trust in people and using data. We always come back to the data. The data to help me understand what’s going on with my teams, but also helping those leaders do the same thing, where they’re not micromanaging, but they’re driving and understanding where they can be helpful on reducing friction on their teams as well.

Shane Hastie: And cycling back to another point that you made that’s hanging over us all at the moment, the Great Resignation. Keeping things flowing through it and retaining great people, how do we do that?

Advice on retaining people [21:27]

Lilac Mohr: The first thing is you need to value your people. It sounds really easy, but a lot of people don’t genuinely care about people at the level that they should. I remember I was interviewing for a leadership role for a very small company, and the owner of the company made some offhanded remark about engineers are a dime a dozen. And I remember having a very strong reaction to that comment and trying to think about it. Was my reaction due to me thinking that engineers need to be treated like special snowflakes? Is it because of my experience with hiring new engineers and how difficult that was?

And I think what it came down to is you can’t have a successful company at any level unless you really value all the individuals there. And you’re not going to have individuals put in their best work unless they know that they’re cared for, that they’re valued. I think it all comes down to that, putting people first. Not thinking about people as resources but as human beings, and I think that that helps with retention.

Shane Hastie: And when we do lose people, as inevitable in these times, how do we let them go well?

Lilac Mohr: We need, as a group, to celebrate the opportunities that they have, and leaders can set the stage for that. I think that if a leader handles someone leaving well, then the rest of the organization feels like it’s okay, it’s not something that they need to panic about. And I think that a lot of times I question my own leadership abilities in different areas, I think everyone does. But some feedback I’ve heard that made me feel really good is that I can be a calming force amidst all the change. And I remember talking to one engineer who admitted that they were thinking about leaving. So it was about a year ago they were thinking about leaving and seriously considering it and not happy. And they decided to stay because of me, because of a discussion they had with me.

To me, just knowing that even if I saved one person and made them feel like they can have a successful career staying here at Pluralsight, that gives me validation that I did my job as a leader. You can’t save everyone, but if you can make a difference, even in just one engineer’s life, I think it’s worthwhile.

Shane Hastie: And then the flip side of that, how do we bring people into the organization well?

Onboarding people well [24:14]

Lilac Mohr: A lot of times we’re looking in the wrong places we’re looking for, “Let’s bring in the top talent,” instead of thinking, “How do we bring in really good people and then be able to grow them?” I think that mind shift helps us bring in people who feel like they’re going to belong. We know that they can have good problem-solving skills, that they’re going to work together with their team members, that they’re hungry to learn to solve these problems. And I think those sometimes make the best engineers, especially in the long-term, because then you get to cultivate them and be able to watch them grow and learn.

I think that’s definitely the first step, is thinking about who you’re hiring and why. We know that diverse teams are better performing teams. Bringing in that diversity and then making sure that it’s not checking a box, it’s bringing in the best people, and then making sure they feel like they belong, I think is really playing the game for the long-term. Making sure that you’re building a healthy team, not just for now, but into the future.

Shane Hastie: Lilac, thank you very much for taking the time to talk to us today. If people want to continue the conversation, where do they find you?

Lilac Mohr: They can find me on LinkedIn. And we’re constantly hiring, so don’t hesitate to reach out.

Shane Hastie: Wonderful. Thanks so much.

Lilac Mohr: Thank you.

Mentioned

.

From this page you also have access to our recorded show notes. They all have clickable links that will take you directly to that part of the audio.

MMS • Anthony Alford

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

The BigScience research workshop released BigScience Large Open-science Open-access Multilingual Language Model (BLOOM), an autoregressive language model based on the GPT-3 architecture. BLOOM is trained on data from 46 natural languages and 13 programming languages and is the largest publicly available open multilingual model.

The release was announced on the BigScience blog. The model was trained for nearly four months on a cluster of 416 A100 80GB GPUs. The training process was live-tweeted, with training logs publicly available throughout for viewing via TensorBoard. The model was trained with a 1.6TB multilingual dataset containing 350B tokens; for almost all of the languages in the dataset, BLOOM is the first AI language model with more than 100B parameters. BigScience is still performing evaluation experiments on the model, but preliminary results show that BLOOM has zero-shot performance on a wide range of natural language processing (NLP) tasks comparable to similar models. According to the BigScience team:

This is only the beginning. BLOOM’s capabilities will continue to improve as the workshop continues to experiment and tinker with the model….All of the experiments researchers and practitioners have always wanted to run, starting with the power of a 100+ billion parameter model, are now possible. BLOOM is the seed of a living family of models that we intend to grow, not just a one-and-done model, and we’re ready to support community efforts to expand it.

Large language models (LLMs), especially auto-regressive decoder-only models such as GPT-3 and PaLM, have been shown to perform as well as the average human on many NLP benchmarks. Although some research organizations, such as EleutherAI, have made their trained model weights available, most commercial models are either completely inaccessible to the public, or else gated by an API. This lack of access makes it difficult for researchers to gain insight into the cause of known model performance problem areas, such as toxicity and bias.

The BigScience workshop began in May of 2021, with over 1,000 researchers collaborating to build a large, multilingual deep-learning model. The collaboration included members of two key organizations: Institute for Development and Resources in Intensive Scientific Computing (IDRIS) and Grand Equipement National De Calcul Intensif (GENCI). These provided the workshop with access to the Jean Zay 28 PFLOPS supercomputer. The team created a fork of the Megatron-DeepSpeed codebase to train the model, which used three different dimensions of parallelism to achieve a training throughput of up to 150 TFLOPs. According to NVIDIA, this is “the highest throughput one can achieve with A100 80GB GPUs.” Training the final BLOOM model took 117 days.

Thomas Wolf, co-founder and CSO of HuggingFace, joined a Twitter thread discussing BLOOM and answered several users’ questions. When asked what compute resources were necessary to use the model locally, Wolf replied:

Right now, 8*80GB A100 or 16*40GB A100 [GPUs]. With the “accelerate” library you have offloading though so as long as you have enough RAM or even just disk for 300GB you’re good to go (but slower).

Although BLOOM is currently the largest open multilingual model, other research groups have released similar LLMs. InfoQ recently reported on Meta’s OPT-175B, a 175B parameter AI language model also trained using Megatron-LM. Earlier this year, EleutherAI open-sourced their 20B parameter model GPT-NeoX-20B. InfoQ also reported last year on BigScience’s 11B parameter T0 model.

The BLOOM model files and an online inference API are available on the HuggingFace site. BigScience also released their training code on GitHub.

MMS • Marcelo Wiermann

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Key Takeaways

- Consumer-grade UX is a game changer for enterprise SaaS.

- Starting at the team-level means starting today, not someday.

- Don’t work in a vacuum. Understand the business, the product and what customers and end-users like and don’t like about it today.

- Turn end-users into advocates. Connect with them early in the process, check in with them regularly and track their satisfaction.

- Keep iterations short and build momentum as data starts coming in.

Modern enterprise applications need to care about the end-user if they wish to thrive in 2022 and beyond. Many enterprise application companies are now using the same UX concepts once reserved for their consumer cousins – and for a good reason. Companies that implement this concept, commonly called “consumer-grade UX”, have consistently outperformed their more drab competitors in end-user adoption rates, end-user advocacy, workflow efficiency, market share, and revenue.

Why

In the distant past (i.e., early 2000’s), the UX of enterprise applications was not considered a significant adoption or sales driver. Managers looked at feature sheets, compared the cost of different services, carefully weighed the pros and cons, and, finally, made purchasing decisions based on which salesperson responded the fastest. Users would adopt because their boss told them to, and that was that.

But something changed around 2010. Slack launched and, fast forward to 2014, overtook the then incumbent Hipchat by Atlassian (yes, the JIRA folks). Many other companies – Dropbox, Asana, Google, etc. – started making a similar decision to Slack’s: applying the same principles used to provide consumers with a great user experience to their enterprise applications.

The user became the decision-maker. The brilliance of those companies in exchanging the UX equivalent of a gas station for something people like to use was twofold. First, because users are more efficient and effective when using systems that are well designed; second, because end-users become advocates within their companies to adopt solutions that they like, especially if they used them before. These factors, combined, transformed those brands into professional household names. In Slack’s case, they became a verb.

There are two cases where these UX overhaul projects tend to be required. First, established companies who wish to serve their customers better, have new leadership with new ideas or have modern, nimbler alternatives eating their market share. Second, fast-growing startups that have optimized for implementation speed at first to prove their product-market fit, but now have mounting design debt and increasingly less forgiving users as they move past the early adopter category.

How

Implementing consumer-grade UX in an existing product is resource-intensive, time-consuming, and presents considerable risk (“why change a winning team?”). Decision-makers may see such investments as a waste of time since they take time away from developing new features, improving software quality, and fixing bugs.

It is possible to execute a full scale UX overhaul top-down, with extensive redesigns and long term plans involving multiple teams. These projects, however, require a lot of organizational will, support from upper management, upfront investment and other luxuries. We are not going to focus on those.

Instead, let’s focus on something that any team can start today: kickstarting a UX revolution, one iteration at a time. There are four main phases to making that happen:

- Understand the status quo.

- Design a workable solution and get buy-in.

- Execute a pilot test.

- Iterate and build upon the momentum.

Learn & Understand

The first step is to understand the business, the application, the current limitations, and the end-user before going to the drawing board. You need to answer who your customer is, your end-user, what you are selling them, their key objectives and critical tasks, how much they are paying you, and what contributes to your cost.

Many good consumer-grade UX overhaul projects never get past the initial concept phase. As tragic as that may be, decision-makers are not necessarily wrong. I have seen many engineers, product managers, and designers develop idealistic proposals that get fast-tracked to the “maybe” pile and, then, into oblivion. The two major problems of such proposals are that they either don’t solve real problems or fail to speak the language of business.

Competent decision-makers are always thinking about serving their customers better – and getting more value from them in the process. If you want to grab their attention and obtain their buy-in, you need to show that you understand the status quo and discuss changes in terms of OKRs, KPIs, ROIs, roadmaps, and more.

Start by learning about the business, the product, the customers, the end-users, and their pain points. One way to do that is by talking with product managers, senior engineers, customer support managers, and, in startups, the founders. As questions like what are you selling? Who is buying? Why are they buying it? What is the price structure? How much does it cost for you to provide those services? Who is the user? What are the major tasks that they need to do?

Another valuable source of information is your data. You want to analyze two types of key performance indicators (KPIs): lagging or output KPIs and leading or input KPIs. The first type tells you if the users got what they needed, and the second tells you if they are having difficulties getting there.

Examples of output KPIs are the Net Promoter Scores (NPS), the System Usability Score (SUS), how many key tasks are completed in a given time, and the cost per key task. Examples of leading KPIs are the time it takes for users to accomplish key tasks (and their error/rejection rate). You need both types of KPIs. If you lack some (or all) of them, start by working with teams to begin implement tracking them.

Pro-tip: put a lot of thought into capturing human KPIs associated with how much users like using the application. Don’t underestimate the power of joy. One of the core differentiating factors in early Slack vs. Hipchat was how easy they made it for users to find and send animated GIFs.

Here’s a real-world example: I led the engineering team at a fast-growing AdTech company in the US that operated a DSP (Demand Side Platform). Our customers were marketing agencies and major brands with in-house ad teams. Our end-users were their ad operators and campaign managers, who used our product to set up digital campaigns, track their progress, make adjustments, and report on their outcomes. Main KPIs were the time to set up campaigns, the freshness of our analytics, time to generate reports, and on-target delivery rate.

The folks driving the frontend part of the project did such a phenomenal job and cared so much about great UX that we won the 2015 UX People’s Choice Award.

Design & Sell

The next step is to design a workable solution and get the buy-in of the necessary decision-makers. Start by using your business knowledge to identify the most significant challenges with the highest potential for impact. Those are usually connected with your lagging and leading KPIs and aligned with the main tasks the end-users have to perform.

Pick the highest ROI challenge you deliver and focus on it. Impact defines the return on investment (ROI), and the implementation cost defines the investment. It’s essential to pick a meaningful problem so that fixing it matters and pick something manageable so that you can deliver. If this first iteration fails, the whole process could fizzle out. Choosing a specific problem to focus on allows you to start now and not after a lengthy planning and review process. Finally, make sure that this is a two-way door decision – i.e., one you can reverse without significant impact to the business in case things go awry.

Once you have chosen a challenge, identify its end-users, their pain points, the KPIs you need to improve and work backward from them to design a minimum lovable solution. The key to moving fast and adapting is the Build-Measure-Learn iterative cycle – build something, see how it works in the real world, learn from the experience, rinse and repeat. At the same time, since you are explicitly addressing UX, go the extra mile between viable and lovable.

At this point, you should have a workable design based on a concrete understanding of the underlying business mechanics and end-user needs. It should also have measurable targets on meaningful KPIs. The final step is to get the buy-in from stakeholders.

To successfully pitch the project to whoever you need to get the buy-in from – a product manager, engineering manager, teammates, etc. – you need to tell a good story. Start with the why: show what problems you are solving and why they matter in the business context and current objectives. Then follow on to the expected impact, what the solution will look like, and, finally, how much time/money/people it will take to make it happen. Many of the same rules of pitching a new business apply here.

Pro-tip: consider the timing of your change. Pitching a UX-centric change at the wrong time – for instance, while the team is dealing with a major technical problem or going through a security audit – can come across as tone-deaf and likely won’t get you the full attention of the people you need. Use your best judgment, but examples of good times to pitch are right after a successful release, during quarterly planning, or while having a coffee with a product manager (never underestimate the power of a 1o1 coffee).

In my previous example, we found that our initial approach to the setup of ads by operators, which was on par with the rest of the industry, was cumbersome, repetitive, and error-prone. Operators have to set up dozens – sometimes hundreds – of ads in a short time, and even minor mistakes at this stage can lead to a lot of time and money wasted. I’m pretty sure an LA restaurant doesn’t want to run their ads in Australia.

We overhauled this process by improving the UX of the forms involved and adding lots of automation. We made some sections optional, implemented a multi-stage process, and added features like restricting the search of cities based on the selected country/state and support for importing bulk ad configurations directly from customers. These changes resulted in a significantly lower time to set up ads and campaigns, fewer setup mistakes, less wasted marketing budget, and happier, less stressed operators.

Pilot Test

You have understood the business, designed an awesome solution, and gotten the buy-in you needed. The next step is to execute it.

Think of the first consumer-grade UX change as a pilot program. Ensure that you have all the necessary tracking in place, especially for the core metrics you are trying to improve. Automate as much tracking as possible using tools like Google Analytics, Hotjar, Kissmetrics, Data Dog, and others. However, if automation is not possible, don’t let that stop you – find ways to manually track the numbers you need, even if you need to flex your Excel skills. Don’t run blind.

Pro-tip: get regular feedback from willing end-users to get their qualitative perspective. Numbers alone tell you only part of the story. You need quantitative and qualitative information to understand what’s going on.

If possible, run your pilot as an A/B test using the old version as a baseline. A/B tests ensure that you compare apples to apples and that any improvements – or problems – are coming from the new design.

Prepare to iterate fast as data and end-user feedback starts coming in, and don’t let your biases cloud your analysis. Understand what the data is telling you and plan your next changes accordingly. These changes could be minor or significant, depending on your results. Either way, plan according to your time budget, keep stakeholders informed, act fast and keep a changelog of what you are doing and why you are doing it.

In my example, we had not originally planned on introducing bulk ad imports so early on. We had to move that feature up the schedule during the overhaul project once it became clear from operator feedback that improving the input process was great, but it was not enough. Operators had crunch times (ex: when first setting up large campaigns), and, as it turned out, they already had a semi-standard file format for describing ads in use.

Iterate & Keep Going!

Consolidate your learnings once the pilot is over. Interview customers and end-users to get their holistic perspective on what you implemented. Collate the information from your changelog and understand what worked (and what didn’t), why it worked and why it failed. The full picture will help you determine if this change was successful and going in the right direction.

Independently of whether the pilot worked and you achieved your objectives, present the results, learnings, and conclusions to the team and key stakeholders. This will build credibility and establish a solid shared knowledge foundation to build upon.

Look at the big picture and think about more systemic changes. Your knowledge from the pilot taught you more than just how to do better in the next iteration – it showed you a glimpse of patterns that can scale-out throughout the application. Start creating an overarching vision and toolset that can tie everything together and create consistency across your future iterations. This can include a common design language, consistent form elements, use of shortcuts, when to sync wait or run a background job, etc.

The pilot is not the end – it’s the first step in your revolution. Capitalize upon the momentum of this first iteration, factor in what you learned from it, and pick one or more high ROI challenges to tackle next. It will be easier to pitch them this time as there are fewer unknowns. Don’t stop now!

Conclusion

You can start a consumer-grade UX revolution at your company today. You don’t have to make a big deal out of it or let analysis paralysis shackle your team. Kick that off by understanding your business, designing a solution for a high-impact-but-still-deliverable case, pitching and getting the buy-in you need, running a data-driven pilot program, and, finally, using the momentum to build a vision and tackle the next challenge.

We were at a very technically focused moment in our DSP when we ran our first UX overhaul iteration. We had to process 100K+ transactions per second, run complex planning and ML algorithms in milliseconds, and create analytics data pipelines that processed multiple terabytes of data per day—all with a startup budget and a small (but plucky) team. UX was not our focus, and we were content with following the competition in that regard. Our first pilot test changed that for engineers and executives alike.

It was, quite literally, the spark that ignited a revolution.

Microsoft Introduces a New Way for Faster Building Cloud Apps with Azure Developer CLI

MMS • Steef-Jan Wiggers

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Recently Microsoft introduced the public preview of the Azure Developer CLI (azd) — a new, open-source tool that accelerates the time it takes to get started on Azure. It provides developer-friendly commands that map to essential stages in the developer workflow: code, build, deploy, monitor, and repeat.

The Azure Developer CLI is designed to set up the resources developers need to run their applications in Azure. According to the Microsoft documentation, the recommended workflow for the Azure Developer CLI is:

- Template selection

- Get and deploy workflow

- Change code, commit and automatically deploy to running apps

Source: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/developer/azure-developer-cli/overview

Developers can use various commands such as azd init, azd provision, azd deploy, azd monitor, and azd pipeline config. Also, Savannah Ostrowski, a Senior Product Manager, Cloud Native Developer Tools & Experience at Microsoft wrote in a developer blog post:

Better yet, you can also use azd up to create, provision, and deploy a new application in one step! For a list of supported commands, see the Developer CLI reference docs. Alternatively, run azd –h from your preferred terminal after installation. If you no longer want or need the resources you’ve created, you can run azd down.

However, Dana Epp, a Security Engineer, and Researcher at Vulscan Digital Security, warned in a tweet:

What’s the worst thing for MORE shadow IT for cloud admins to fret about?

It’s sexy. Powerful. And puts potential company resources at risk.

Friend’s don’t let friends ‘right-click deploy’. And they shouldn’t allow `azd up` without isolation.

Note that every template comes with source code, infrastructure code, pipeline files, and configuration needed to run the entire solution on Azure and local run and debug in VS Code and Visual Studio. Furthermore, guidance is available through the documentation landing page and getting started video.

A respondent in a Reddit thread on the Azure Developer CLI said:

Looks like another wrapper for something that was already solved. Deploying IaC and applications to PaaS is easy enough with CI/CD tasks. I guess the tool is nice if a developer needs to deploy a test cloud infrastructure and application from a local computer. Still going to test out in CI/CD because never know until used.

Currently, the Azure Developer CLI is in public preview and includes support for Container Apps, Functions, Static Web Apps, & App Services in Node, Python, and C#. AKS and Java are coming soon. Microsoft uses Bicep in current templates, while other IaC providers, like Terraform, are in the works.

MMS • David Manda

Article originally posted on Database Journal – Daily Database Management & Administration News and Tutorials. Visit Database Journal – Daily Database Management & Administration News and Tutorials

![]()

![]()

Changes in customer behavior have caused a new focus for the structure of commercial databases. The flexibility of data storage is essential in fulfilling the demands of customer needs and predicting future business. MongoDB and MySQL are both valuable database solutions that align to this shift in commercial objectives in database management systems. The difference between the two applications is that MongoDB is an object-based system, while MySQL is a table-based system.

For its part, MongoDB is a database that features bulk data storage through a NoSQL

structure in a document format. The main feature of this software is the option to modify documents and their variables. MySQL, meanwhile, functions through a query system where data can be searched and its point of relation identified.

When deciding between MongoDB vs. MySQL, having knowledge of the language structure is important. MongoDB simplifies the data query process, but MySQL has a proven record of Structured Query Language (SQL) for defining and manipulating data. In order to understand which software is better, this database programming and administration tutorial will analyze the features of these applications to identify which one is better.

If you opt to choose MySQL as your database of choice, you should check out our article: Best Online Courses to Learn MySQL, which has a great list of database administration classes that will help you get started.

What is MongoDB?

MongoDB is a database management system that uses NoSQL queries, while providing flexibility and scalability functions. MongoDB is a non-relational database system that uses the JavaScript language to search data and modify documents into smaller sizes. Commercial companies rely on MongoDB because it is compatible with multiple storage engines.

The database management software retains a dynamic structure that favors the organization of information, making data modification faster than other database options. This process also makes data management more efficient and faster, especially when large documents need to be encoded into smaller sizes. MongoDB uses JSON and BSON languages to make data management more flexible and lighter to process when compared to MySQL.

MongoDB faces competition from 20 NoSQL database vendors. It leads the market share of other NoSQL databases with a 48.05% lead. The major competitors of MongoDB include NoSQL, with 24.41%, Amazon DynamoDB at 9.74%, and Apache Cassandra with 5.56%. The United States has the highest number of customers of MongoDB with 33.41%, followed by India with 9.95% of customers, and the United Kingdom with 5.84% of users.

MongoDB is typically used for designing specialized data sets through document compression and is able to adapt to data variations. Geospatial data format does not require technical monitoring when structures show variation, because MongoDB has resilient data structures. MongoDB also functions in multi-cloud application environments. The database system can execute cloud services based on personal configuration to support both current and future software needs. Healthcare, gaming, retail, telecommunications, and finance industries – to name but a few – rely on MongoDB for software development for database-driven applications, data management, data analytics, and solutions to server issues.

Benefits of MongoDB

Below are some of the key benefits of MongoDB:

- Scalability is a significant benefit of using MongoDB because it is easy to organize the database system laterally and scale per software requirements.

- The storage structure of MongoDB supports the addition of any file regardless of its size without disrupting the file stack.

- MongoDB can improve the performance of database systems with the configuration of indexes. Documents that use MongoDB can alternate the index field.

- MongoDB improves the performance of servers by adjusting the data load or replicating files when the system is struggling. The application also supports multiple servers and offers improved functionality over other options.

- Aggregation process is possible when using MongoDB, which means aggregation commands, aggregation pipeline, and map reduce operations are supported.

- The replication of documents in the database is quicker and more flexible when using MongoDB.

What are MongoDB’s Cons?

Below are some of what we consider to be MongoDB’s cons and negatives:

- MongoDB has a complex procedure for performing transactions that is tedious and time consuming.

- ACID (Atomic, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability) certification is absent in the system catalog, especially for data transactions. This feature is available in other relational database management systems.

- MongoDB does not operate like most relational database systems, which means it lacks support for Stored Procedures or commands. The addition of a business structure is impossible in the database system.

You can learn more about MongoDB’s latest features and updates by reading our cousin sites coverage of MongoDB’s Conference.

What is MySQL?

MySQL is a relational database system that serves client-server systems in storing data. It is a reliable system that supports the classification of data in rows and tables. MySQL operates through the master-slave approach, where replication and backup of data is possible, making it very reliable. Atomic Data Definition Language is also possible with MySQL, which provides storage engine operations and updates for the data dictionary to simplify transactions.

MySQL ranks second in the world in the database market. The relational database management system has 44.04% of the market share based on its support for web development and applications like phpBB and WordPress. MySQL is easy to customize and is open-source software.

Small, mid-sized, and large enterprises can use MySQL for data storage management because of its built-in functions. The software has a 31.39% market share in the USA and has a proven record of being scalable to major business functions, like marketing. Twitter and Facebook are popular social media websites that were developed, in part, through MySQL. Oracle is the major competitor to MySQL in the database management market.

Benefits of MySQL

Below are some of the benefits of using MySQL:

- The security protocols used in MySQL are complex enough to prevent exposure of private databases when developing web applications. Web designers can rely on security algorithms that deny exposure of information, especially for regular web users.

- MySQL can function on multiple servers and is easily accessible to most database systems. The high portability of the software makes it easier for users to complete web functions from any location.

- Since MySQL is open-source software, any web developer can use its services to store and manage data for most functions. Commercial enterprises with limited investment can use the database system to grow their business with little effort or cost.

Cons of MySQL

Some of the cons of MySQL include:

- MySQL lacks a server cache for stored procedures. This condition means the operator must repeat the data input procedure after the process concludes.

- The system catalog is susceptible to corruption when a server crash occurs. This process can cause loss of data and time spent recovering the database system.

- MySQL cannot process bulk data, which can limit the performance ability of commercial enterprises. The software is not as fast as industry standards for data processing.

- Support for MySQL is limited because it is open-source software. This condition means security updates or reports on server bugs may not be as available compared to paid subscription software. MySQL cannot support innovative web development functions especially significant to commercial companies.

Read: Top Common MySQL Queries

Database Comparison: MySQL versus MongoDB

Below, we compare the differences between MySQL and MongoDB database solutions.

User-friendliness

MongoDB is more user-friendly than MySQL. MongoDB has a predefined structure that supports the entry of different information to the database without having similar fields. However, MySQL demands the configuration of columns and tables. Also, the structure of the database cannot be changed depending on the number of columns.

In terms of structured and unstructured data, MongoDB is better than MySQL; this is because MongoDB functions as an object database system, while MySQL functions as a relational database system. The support for a database system with rapid web development is possible with MongoDB and not MySQL.

Features

MySQL uses the Structured Query Language – or SQL – while MongoDB functions through JavaScript as a query language. Some consider MongoDB is to be better than MySQL because the design of data structures is limitless.

MongoDB supports cloud-based services that are essential to online transactions and data storage management. MySQL does not support cloud-based services because its priority is data security. MongoDB is better than MySQL because of this feature gets a slight edge here if you are a cloud developer.

Software support is consistent with MongoDB because the company publishes bug reports and security updates as a part of the ongoing development of the software. Oracle develops updates and fixing problems relating to MySQL. However, the updates are not frequent on MySQL, which makes MongoDB the winner here.

Integrations

MongoDB integrates with multiple storage engines with a dynamic structure design that favors simpler configuration for data management. The software uses JSON language and MongoDB query language to change the structure of JSON and BSON documents. In contrast, MySQL uses the Structured Query Language to organize and manage databases. MySQL supports C, C++, and JavaScript languages. MongoDB is more flexible than MySQL in integrating databases because it can embed additional data in existing file stacks. From an integration perspective, these two are evenly matched.

Collaboration

MySQL makes it simpler easier to execute structured commands because it uses Structured Query Language. This condition means creating commands for data queryries is easier because of Data Definition Language and Data Manipulation Language. With MySQL, you can link several documents and data with minimal commands. In contrast, MongoDB requires several commands to execute data configurations because it uses a non-structure system. MySQL is better for collaboration because combining different files is easier in MySQL than it is in MongoDB.

Pricing

MySQL is better than MongoDB in pricing for small businesses and individuals because it is open-source software. This standard means that any web developer or business can use the software for database system management. The Enterprise Edition of MySQL costs $5000 annually for web developers and end -users.

MongoDB requires a licensing fee for its Enterprise Edition that includes additional security protocols, data monitoring, authentication, administration, and a memory storage engine. This package costs $57 per month. The open-source version of MongoDB is less advanced in functionality compared to the paid option. For this reason, MongoDB is better than MySQL..

The Verdict: MySQL or MongoDB

MongoDB is better than MySQL because it takes a shorter time into query data, which is that is important for managing databases relating to customer behavior. Although when handling structured data, MySQL is better than MongoDB,; when there is a query against unstructured data, MongoDB is preferential. In the database management market, speed and performance are significant to many businesses. MongoDB can deliver speed and performance given its fast queries of data, as well as the ability to handle both structured and unstructured data.

Real-time analytics is a benefit that comes with MongoDB and gaining quick query results is possible through object database systems like MongoDB. With MySQL, the data queries take longer, so configuration can delay after updates. However, in terms of security protocols to protect private information, MySQL is better than MongoDB because it uses a relational database system.

At the end of the day, there are many factors that might make you choose one database over another. Weigh the benefits and drawbacks of each against the needs of your particular project.

Looking for more database comparisons? Check out our article on PostgreSQL vs MySQL.