Month: July 2022

MMS • Anthony Alford

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

The PyTorch open-source deep-learning framework announced the release of version 1.12 which includes support for GPU-accelerated training on Apple silicon Macs and a new data preprocessing library, TorchArrow, as well as updates to other libraries and APIs.

The PyTorch team highlighted the major features of the release in a recent blog post. Support for training on Apple silicon GPUs using Apple’s Metal Performance Shaders (MPS) is released with “prototype” status, offering up to 20x speedup over CPU-based training. In addition, the release includes official support for M1 builds of the Core and Domain PyTorch libraries. The TorchData library’s DataPipes are now backward compatible with the older DataLoader class; the release also includes an AWS S3 integration for TorchData. The TorchArrow library features a Pandas-style API and an in-memory data format based on Apache Arrow and can easily plug into other PyTorch data libraries, including DataLoader and DataPipe. Overall, the new release contains more than 3,100 commits from 433 contributors since the 1.11 release.

Before the 1.12 release, PyTorch only supported CPU-based training on M1 Macs. With help from Apple’s Metal team, PyTorch now includes a backend based on MPS, with processor-specific kernels and a mapping of the PyTorch model computation graph onto the MPS Graph Framework. The Mac’s memory architecture gives the GPU direct access to memory, improving overall performance and allowing for training using larger batch sizes and larger models.

Besides support for Apple silicon, PyTorch 1.12 includes several other performance enhancements. TorchScript, PyTorch’s intermediate representation of models for runtime portability, now has a new layer fusion backend called NVFuser, which is faster and supports more operations than the previous fuser, NNC. For computer vision (CV) models, the release implements the Channels Last data format for use on CPUs, increasing inference performance up to 1.8x over Channels First. The release also includes enhancements to the bfloat16 reduced-precision data type which can provide up to 2.2x performance improvement on Intel® Xeon® processors.

The release includes several new features and APIs. For applications requiring complex numbers, PyTorch 1.12 adds support for complex convolutions and the complex32 data type, for reduced-precision computation. The release “significantly improves” support for forward-mode automatic differentiation, for eager computation of directional derivatives in the forward pass. There is also a prototype implementation of a new class, DataLoader2, a lightweight data loader class for executing a DataPipe graph.

In the new release, the Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) API moves from prototype to Beta. FSDP supports training large models by distributing model weights and gradients across a cluster of workers. New features for FSDP in this release include faster model initialization, fine-grained control of mixed precision, enhanced training of Transformer models, and an API that supports changing sharding strategy with a single line of code.

AI researcher Sebastian Raschka posted several tweets highlighting his favorite features of the release. One user replied that the release:

Seems to have immediately broken some backwards compatibility. E.g. OpenAIs Clip models on huggingface now produce CUDA errors.

HuggingFace developer Nima Boscarino followed up that HuggingFace would have a fix soon.

The PyTorch 1.12 code and release notes are available on GitHub.

MMS • Abel Avram

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

QCon international software development conference returned to London this past April and online with QCon Plus in May.

The conference explored the major trends in modern software development across 15 individually curated tracks. The 2022 QCon London and QCon Plus tracks featured in-depth technical talks from senior software practitioners covering developer enablement, resilient architectures, modern Java, Machine Learning, WebAssembley, modern data pipelines, the emerging Staff-Plus engineer path, and more.

InfoQ Editors attended both conferences. You can read their coverage online.

This article summarizes the key takeaways from five talks presented at QCon London 2022 and QCon Plus May 2022. In addition, it surfaces tweets directly from attendees that were there.

Architectures You’ve Always Wondered About

Shopify’s Architecture to Handle the World’s Biggest Flash Sales by Bart de Water, Manager @Shopify Payments Team

Bart de Water talked about Shopify’s architecture to handle what he called the “world’s biggest flash sales.” His presentation was very technical, covering details about the backend built on Ruby on Rails with MySQL, Redis, and Memcached, with Go and Lua in several places for performance reasons. The frontend is done in React and GraphQL, with the mobile application written in React Native.

He focused mostly on the storefront and checkout because these have the most traffic, the two having different characteristics and requirements, with the storefront mostly about read traffic. The checkout covers most of the writing and interacts with external systems. Shopify supports various payment systems.

According to de Water, Shopify’s main challenge is dealing with flash sales and some weekend sales. To show what scalability issues they are dealing with, de Water said, “Here are last year’s numbers. $6.3 billion total sales with requests per minute peeking up to 32 million requests per minute.” To check that everything works, the team performs load testing in production using Genghis, a custom load generator that creates worker VMs that execute Lua scripts describing the behavior that they want and a resilience matrix simulating an outage to see what happens when one would take place, and what needs to be done to prevent one in production. They also use a circuit breaker to protect datastores and APIs, activating it when necessary.

At the end of the talk, de Water answered specific questions on handling big clients, moving to microservices, pods, scaling the storefront and checkout, using Packwerk to enforce boundaries between teams, and others.

Debug, Analyze, and Optimize… in Production!

An Observable Service with No Logs by Glen Mailer, Senior Software Engineer @Geckoboard

Mailer talked about a microservices project written in Go that they did at CircleCI. They needed a new service for a build agent, and decided to build it in Go (rather than Clojure, as many other services had been). They also wanted a new approach to logging, one that was not based on text logs but rather used what he called an “event-first approach,”—a data-first telemetry instead of a text-first telemetry as it is for regular logs. What takes place in a system is described through events with each having a unique name throughout the codebase identifying what takes place in the system. The properties of the respective event are structured data. The resulting log lines are made of structured data.

He then showed us some Go code on how this event-first observable service is written, mentioning the patterns that emerged while developing it and how they implemented them. Also, he showed the interface built on top of it, using it to visualize logged data and interpret it.

The project started as an experiment, a partial success according to Mailer. He learned a lot about what was important to log. Having a new approach to logging was, in his opinion, much better than logging some text lines when some code gets executed.

What Mailer didn’t like about the result was that it was like “reinventing a bunch of wheels.” He still considered the process valuable for their team because they discovered together what to include and exclude from the library they had built up.

Concluding, Mailer “tentatively recommends this concept of a unified telemetry abstraction, having this one place to produce logs, metrics, and events.” Still, he had some concerns because others did not find the new service as intuitive as hoped. He considered the new logging service good, but not good enough to rip the present system apart and start from scratch. He recommended looking at OpenTelemetry, an open-source project somewhat similar to theirs.

Impressions expressed on Twitter included:

@jessitron: This morning at #QConLondon, @glenathan tells a story of an experiment at CircleCI: for this greenfield project, let’s have NO LOGGING.

@jessitron: Instead of logs, events! that make traces! “Events are good logs.” They’re data-first instead of human-first; they wrap units of work with durations; they can be explored multiple ways @glenathan #QConLondon

@jessitron: They found best practices like: wrap each unit of work; report errors in a standard field; use span names that are specific enough to tell you what’s happening but general enough for useful grouping. ~ @glenathan #QConLondon

@jessitron: Then they tuned the span creations so that there wasn’t a bunch of duplicate-looking ones. Instead of repetitive spans, add more attributes. “Add every identifier you have in your system” to help find problems. @glenathan #QConLondon

@jessitron: If you look at the “three pillars” of observability from the top, it’s all the same events. @glenathan #QConLondon

Profiles, the Missing Pillar: Continuous Profiling in Practice by Michael Hausenblas, Solution Engineering Lead @AWS

Hausenblas discussed the need for observability in large, sometimes distributed systems. He defined observability as “the capability to continuously generate and discover actionable insights based on certain signals from the system under observation.” He mentioned several types of signals: text logs, usually consumed by humans, then metrics, labeled as numerical signals, and distributed traces used for “propagating an execution context along a request path in a distributed system.”

He then added another signal type, namely profiles which he saw in the context of the source code and the running process associated, exploring them to find out more about the system monitored. Unlike metrics, which have their benefits, profiles allow going to a specific line of code that is responsible for a certain metric that is out of normal values.

He also mentioned 3 open source continuous profiling tools that developers can install and use right away:

- Parca—inspired by Prometheus.

- Pyroscope—a rich tool with broad platform support that supports several language profiles and eBPF.

- CNCF Pixie from the Cloud Native Computing Foundation donated by New Relic, currently a sandbox project. It uses eBPF for data collection.

Hausenblas predicted that eBPF will become the “unified collection method for all kinds of profiles.” All profiling tools recommended by Hausenblas use eBPF.

Hausenblas concluded his session by answering questions on Profiling and the Development Life-Cycle, differences between eBPF and language-specific tools, and the missing piece in Continuous Profiling. Highlighting the benefits of using eBPF, he said that eBPF does not care if the program was written in a compiled or interpreted language. Also, it captures both function calls and syscalls, all in one place.

Impressions expressed on Twitter included:

@PierreVincent: “Observability is the capability to continuously generate and discover actionable insights based on signals from the system under observation with the goal to influence that system” and that’s for both people (e.g. debugging) and automation (e.g. autoscaling) @mhausenblas #QConLondon

@PierreVincent: Observability can go beyond usual metrics, logs, and traces: @mhausenblas introducing profiles and eBPF #QConLondon

@PierreVincent: Profiles with sampling are low overhead, so great to apply in production. @mhausenblas #QConLondon

@PierreVincent: High-level architecture of Continuous Profiling, from agent and ingestion to frontend for visualization. @mhausenblas #QConLondon

@PierreVincent: Continuous Profiling with Parca, open-source project, with concepts and query language very close to Prometheus. @mhausenblas #QConLondon

@dberkholz: Three tools for continuous profiling in production: Parca, Pyroscope, and Pixie. All of them support eBPF, which is becoming the unified collection method. -@mhausenblas #qconlondon

@PierreVincent: Looking ahead, eBPF is becoming the unified collection method for profiles. Profiling standards seem to be converging towards pprof with its increasing support @mhausenblas #QConLondon

@estesp: Lots of eBPF today at #QConLondon! My colleague @mhausenblas making the case for continuous profiling as a key observability pillar for your applications.

@PierreVincent: Correlation remains a challenge with profiles, to link together all the different signal types, rather than dealing with multiple independent tools. @mhausenblas #QConLondon

@danielbryantuk: “It is vital to be able to correlate signals and metrics to provide insight into an application” @mhausenblas at #QConLondon

@PierreVincent: Is 2022 the year of Continuous Profiling? @mhausenblas #QConLondon

Effective Microservices: What It Takes to Get the Most Out of This Approach

Airbnb at Scale by Selina Liu, Senior Software Engineer @Airbnb

Liu shared lessons learned at Airbnb during their migration from a monolith to SOA. The first lesson was to invest early in the needed infrastructure because that will “help to turbocharge your migration from monolith to SOA.”

They approached the migration by decomposing the presentation layer into services that “render data in a user-friendly format for frontend clients to consume.” Below those services, they have mid-tier services with various business rules which use data services connected to databases to access data uniformly. After migration, their application was made up of 3 layers: presentation, business, and data running as services. The higher layer may call a lower layer but not the other way around.

Liu then explained using a concrete case how they migrated Host Reservation Details, a certain feature they used, to SOA, as an example to show how they tackled the migration process.

To help with the migration process, they used an API Framework used by all Airbnb services to talk to each other. Then they had a multi-threaded RPC client handling features like error propagation, circuit breaker requests, and retries. That helped engineers focus on the business logic to create new functionality rather than inter-service communication.

After that, she talked about Powergrid, a Java library used to run code in parallel. Powergrid “helps us organize our code as a directed acyclic graph, or a DAG, where each node is a function or a task.” This library enables them to perform low-latency network operations concurrently.

Then she mentioned OneTouch, a “framework and a toolkit built on top of Kubernetes that allows us to manage our services transparently and to deploy to different environments efficiently.” One last piece of useful infrastructure she mentioned was Spinnaker, defined as an “open source continuous delivery platform that we use to deploy our services. It provides safe and repeatable workflows for deploying changes to production.” These pieces of infrastructure helped them migrate their monolith to 400+ services with over 1000 deploys daily over 2-3 years.

She also mentioned that “as we continue to evolve our SOA, we also decided to unify our client-facing API. Our solution to the problem is UI Platform, a unified, opinionated, server-driven UI system.”

As another conclusion, she added that having the UI generated with the backend services allows them to have a “clear schema contract between frontend and backend, and maintain a repository of robust, reusable UI components that make it easier for us to prototype a feature.”

Liu’s session ended by answering questions, one of them regarding the use of SOA instead of microservices. She said “I think, tech leaders at that time, they really just used the word SOA to push the concept wider to every corner of the company. I think partially it might be because, at the start, we were wary of splitting our logic into tiny services. We wanted to avoid using microservices, just because the term might be a little bit misleading or biased in just how it’s understood by most people when they first hear it. It’s probably just like the process of how we communicate it, more than anything else.”

Liu also talked a bit about the technologies used and the benefits resulting from migration.

Impressions expressed on Twitter included:

@danielbryantuk: “building and deploying services at @AirbnbEng is easy due to all code and config being located in one place, and our use of tooling to provide key abstractions and simple command-line actions” @selinahliu #QConLondon

@danielbryantuk: Four pieces of advice from @selinahliu at #QConLondon in relation to the @AirbnbEng migration from a monolith to microservices – invest in common infra – simplify service dependencies – platformize data hydration – unify client-facing API

Pump It Up! Actually Gaining Benefit from Cloud Native Microservices by Sam Newman

In this session, Sam Newman discussed cloud and microservices, what to do about them to succeed, and shared some tips on how they should be done and certain pitfalls to avoid. He started by wondering why cloud-native and microservices have not delivered as expected.

Part of the unsuccessful pairing of cloud and microservices is, in his opinion, a certain level of confusion on the role of the cloud in an organization. He tells the story of visiting a company in Northern England where developers said they wanted access to the cloud. When he told their desire to the CIO, he discovered they already had access to the cloud. It turned out that if a developer wanted access, he had to create a JIRA ticket and someone from the system administration would intervene and provide the needed access. It was like using a resource on premises in the old way but now in the cloud. This made the process inconvenient for developers, slowing the entire development process.

Talking about the revolution introduced by AWS with cloud computing, Newman said “AWS’s killer feature wasn’t per-hour rented managed virtual machines, although they’re pretty good. It was this concept of self-service. A democratized access via an API. It wasn’t about rental, it was about empowerment.”

He continued inviting leaders to trust their people, adding “this is difficult because, for many of us, we’ve come from a more traditional IT structure, where you have very siloed organizations who have very small defined roles.” To address this issue he suggested leaders think in terms of long-lived product teams who own major parts of the project—think “holistically about the end-to-end delivery of functionality to the users of your software.”

That’s why Newman considered microservices to be of particular value because teams can own their microservice.

Besides this ownership issue, Newman pinpointed the lack of proper training in using the tools they have as a pitfall to a project’s success. He considered it not enough to throw some tools at them but follow up with the necessary training on using those tools.

Going further, he advised creating a good developer experience by treating the microservices platform as a product, talking to developers, testers, and security personnel to find out what they need to succeed, to create an “experience for your delivery teams that makes doing the right thing as easy as possible,” making developers, testers, sysadmins your own customers.

Impressions expressed on Twitter included:

@danielbryantuk: “There is a danger with platform abstractions that we artificially create constraints that stop people getting their work done” @samnewman discussing there may be no one-size-fits-all platforms at #QConLondon

@danielbryantuk: “The job of the platform team is not about building the platform, it’s about enabling developers. This includes outreach, training, and more. If you do build a platform, treat it as a product” @samnewman #QConLondon

@danielbryantuk: Beware of your platform becoming a requirement rather than an enabler… @samnewman #QConLondon

@danielbryantuk: “if you focus on durable, product-focussed teams, you can reduce the governance and centralized control required to make progress” @samnewman #QConLondon

@danielbryantuk: “Make your platform easy to use. This is essential if your platform is optional. A platform with no users should generate a lot of reflection” @samnewman #QConLondon

MMS • Steef-Jan Wiggers

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

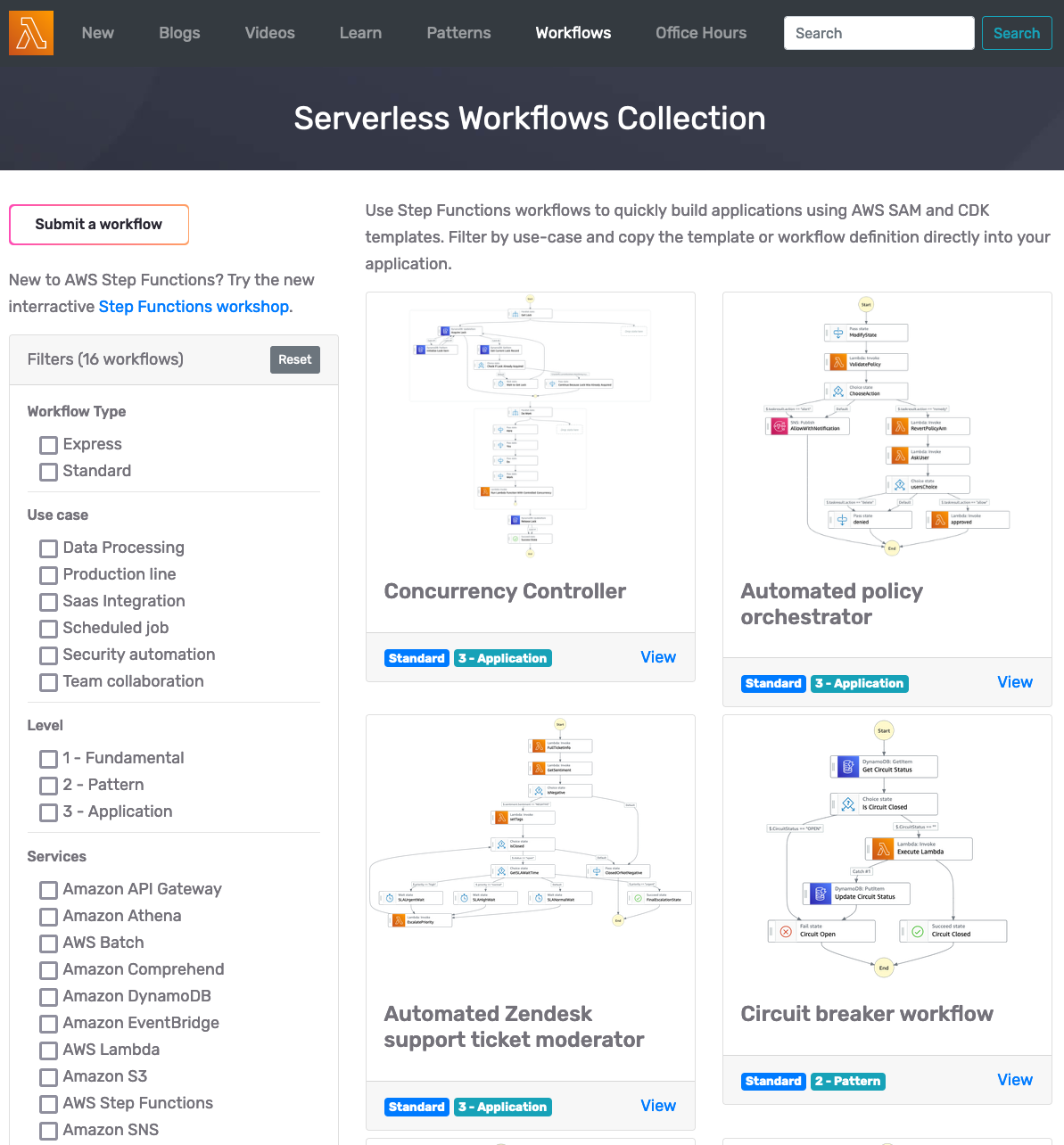

AWS Step Functions is a serverless function orchestrator that makes it easy to sequence AWS Lambda functions and multiple AWS services into business-critical applications. AWS recently introduced a new experience to its Step Functions with Function Workflow Collections allowing users to create Step Functions workflows easier.

The Function Workflow Collection is an initiative of the AWS Serverless Developer Advocate team that launched a new Serverless Land experience hosting the templates. The team intends to simplify the Step Functions getting started the experience with the collection for its users and allow more advanced users to apply best practices to their workflows.

Step Functions workflows are made up of a series of steps in which the output of one step is used as input for the next. Furthermore, Step Functions can integrate with over 220 AWS services using an AWS SDK integration task, allowing users to directly call AWS SDK actions without having to write additional code.

By exploring the workflow collection, users can search for templates in a collection suiting their use cases. The collection has three levels of workflows:

- Fundamental: A simple, reusable building block.

- Pattern: A common reusable component of an application.

- Application: A complete serverless application or microservice.

Source: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/compute/introducing-the-new-aws-step-functions-workflows-collection/

By selecting a template, users can view the template diagram, the infrastructure as code (IaC) deployment template (defined with AWS Serverless Applications Model (AWS SAM) or the AWS Cloud Development Kit (AWS CDK)), and workflow definition (Amazon States Language definition (ASL)). Next, users can choose how to deploy the template into their AWS accounts. And finally, once users deploy the workflow into their AWS account, they can continue building in the AWS Management Console with Workflow studio or locally by editing the downloaded files.

Dan Ronald, Principal PM for Step Functions at AWS, tweeted:

You asked for more AWS Step Functions examples and we have heard you. Check out the Step Functions Workflows collection. Hope this helps you on your orchestration journey!

In addition, Benjamin Smith, a senior developer advocate for Serverless Applications at AWS, wrote in an AWS Blog Compute post:

Builders create Step Functions workflows to orchestrate multiple services into business-critical applications with minimal code. Customers were looking for opinionated templates that implement best practices for building serverless applications with Step Functions.

Lastly, users leveraging Step Functions can contribute to the collection by submitting a pull request to the Step Functions Workflows Collection GitHub repository. Subsequently, each submission is reviewed by the Serverless Developer advocate for quality and relevancy before publishing.

MMS • Shailesh Kumar

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Key Takeaways

- There are four key areas of focus when pragmatically scaling an organization through hyper-growth: people, process, product, and platform.

- When you’re growing rapidly it’s important to first consider your company goals while remaining practical about how you’re scaling.

- In the hyper-growth stage, all problems look important; you have to prioritize what has short- and long-term benefits to your company and to your users.

- A focus on product will allow you to create a natural product-market fit “flywheel” that is always catered to your customers’ needs.

- A diversity of viewpoints throughout the company will allow you to be pragmatic in determining which problems to immediately address, saving time, money, and energy.

- In today’s tech environment, it’s much easier to integrate with proven solutions in your areas of need rather than starting from scratch.

- Focus on iterative and pragmatic platform development, not big bangs.

- Scaling your organization during a period of hyper-growth is a challenge every founder wants to face. Yet, for engineering leaders in a world of tech debt, shadow IT, app sprawl, and reliability, the concept of “scale” can quickly spiral out of control. To find success, it is important to avoid the pitfalls that lead to speculative decision making, complete re-writes of your code, and delays in delivering customer value. But how?

Preparing to scale an organization through hyper-growth

Scaling challenges look different for every company, and facing them means that you’ve found a market fit with a product that’s ready to take the next step into a much larger pool of potential customers. But, while the importance of planning for growth and focusing on your customers is apparent for any organization, the methodology behind how and when to scale your engineering org is less clear.

I’m in the midst of my own scaling journey with a hyper-growth startup. In less than five years, our company has grown to millions of users and more than 800,000 different teams spread out around the world. In the past two years alone, we’ve increased ARR by $66 million, and we’ve expanded our engineering and product teams by more than 100 people in the past six months. Needless to say, we’ve been busy! While I can’t give you a one-size-fits-all rule on how to scale an organization in hyper-growth, I can what has worked for us.

Introducing the 4 P’s of pragmatically scaling your engineering organization: people, process, product, and platform.

People: Are you building the right organization?

Your people aren’t just the heart and soul of the company, they’re the building blocks for its future.

When you’re growing rapidly it can be tempting to add developers to your team as quickly as possible, but it’s important to first consider your company goals while remaining practical about how you’re scaling. This is the key foundation for building the right organization.

There are two key types of hires when scaling a hyper-growth company: strategic hires and tactical ones. In order to identify the types of additions your team needs, it’s imperative to be realistic about the current phase of your company. Where do you fall in the company life cycle of new product, growth, maturity, or decline? Every phase of the company life cycle has different strategic needs.

We’ve long been told the importance of building a team with diverse skills, but a pragmatic approach requires leadership to dig a bit deeper at this stage. After all, these employees will be building your company for years to come. For us, we sought the help of investors and agencies to identify top talent in the industry and then we spoke to references – a lot of references. No matter the experience, we needed to know that we were making hiring choices that complimented and enhanced our existing team’s core values as much as the product’s value proposition.

Striking a balance between strategic and tactical hires is crucial. Tactical hires – roles that are temporary based on the architecture or maturity of the product journey – are an opportunity to get creative with your hiring process by finding areas where you can rely on contractors and external vendors to build and operate your services.

To us, that meant leaning on a build/operate/transfer model to bring our product to market faster, save costs, and minimize risks during rapid scaling. We also utilized a staffing augmentation model to fill short-term or project-specific roles with temporary workers.

It’s often easy to confuse “important” roles with strategic hires, but the reality is that all hires are important on your growth journey. Many founders commit the fallacy of believing that every hire is permanent, but holding yourself to such a limiting perspective can be dangerous in the long term for organizations scaling through hyper-growth.

When making any hire, ensure that you do so with the product’s core value proposition in mind.

Processes: Balancing short and long term wins

Scaling your processes comes down to practical prioritization. It is crucial to clearly establish processes that balance both short- and long-term wins for the company, beginning with the systems that need to be fixed immediately.

Start by instituting a planning process looking at things from both an annual perspective and quarterly, or even monthly– and try not to get bogged down deliberating over a planning methodology in the first stage. Take a step outside of your organization and look at other big companies who have already taken this step and invested their own resources in testing an approach, then adopt the methodology that feels natural to you and your team. In the planning phase, you will also want to identify your key drivers, drive alignment across functions, and pin down your OKRs before moving forward.

Drawing from your yearly planning, move into a monthly execution cycle with monthly planning and review sessions to analyze business metrics, market analysis, cross-functional initiatives, and monthly team deliverables. Regularly aligning our top goals for the month enables our teams to keep moving forward and helps us maintain a regular cadence between quarterly reviews.

Establishing a process that keeps our growing team aligned has been especially crucial at ClickUp, where we ship updates every week. We are often asked if weekly Sprints actually work with such a short time frame, and the short answer is yes. If you’re deliberately prioritizing projects on a weekly basis, this process can be extremely effective.

During hyper-growth, it’s important to identify and nurture systems that provide leverage to the company and its growth. This is where the prioritization lies in scaling your organization, ultimately allowing you to “leapfrog” the business. For us, this meant focusing on areas such as license and revenue recognition systems, developer tooling, continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipelines, and application performance monitoring.

Be very deliberate in what your team is focusing on and where you’re spending energy. In the hyper-growth stage, all problems look important; you have to prioritize what has short- and long-term benefits to your company and to your users. Always be ready to pivot without worrying about sunk costs.

Product: stay focused on the customer

If your company is entrenched in hyper-growth, it’s no secret that your customers – and their problems – should be at the center of everything you do. But it bears repeating: your customers are critical for the success of your business and are the driving force behind your products!

Customers use and advocate for your product, and in return, it is imperative that you listen to and understand their pain points to solve problems or anticipate them before they arise. Clearly, many companies approaching hyper-growth already do this very well!

In our early days, we began by pinpointing the tools we needed to build for our users to be more efficient. We considered what our users wanted, then chose a solution that would get us at least 70% of the way there, adopting a mindset that we’re always progressing towards perfection. This is the time to compare the opportunity costs of development time with the largest payoffs and align similar features to be developed in parallel. By doing all of the above, you create a natural product-market fit “flywheel” that is always catered to your customers’ needs.

Platform: Leverage best-in-class services, iterate only when needed

Scaling the platform is often the biggest challenge organizations face in the hyper-growth phase. But it’s important to remember that building toward a north star doesn’t mean that you’re building the north star. Now is the time to focus on intentional, iterative improvement of the platform rather than implementing sweeping changes to your product.

At this point, you’ve found a product-market fit, but the platform’s architecture has not scaled with your growing customer base. You may experience operation and performance issues, defects in the code, or tech debt. These are all extremely common – welcome to hyper-growth!

A decade ago, these routine problems would’ve been met with a complete rebuild of the platform’s code. Fortunately, cloud services have made way for several new aspects of architectural scaling that just weren’t possible a short time ago. As a result, you need to be more pragmatic and practical about the choices you make during hyper-growth. Today, it’s counterintuitive and wasteful to spend time, your most vital resource, to rebuild your system as you scale. Instead, leverage best-in-class services and iterate as needed.

Scaling is not just an engineering challenge; it is a product challenge, and therefore it is a business challenge. Involve other stakeholders early for smarter solutions. A diversity of viewpoints will allow you to be pragmatic about determining which problems should be immediately addressed, saving you time, money, and energy.

Stay Smart, Fight the Right Battles, and Save Costs

At ClickUp, we saw the cost of replacing architecture and specific services drop significantly as we started to pick and choose which problems to solve and which to leave untouched. We began by using AWS Native Infrastructure and turned to proven best practices to scale up our architecture, providing a major upside in costs and price leverage. There is often a tendency to monetize from the start by building your own platform, rather than relying on AWS or a similar provider, but this approach can lead to complexities that are simply not needed. Consider what the bulk of your customers need from your product – and use services like AWS to fulfill that vision.

In today’s tech environment, it’s much easier to integrate with proven solutions in your areas of need rather than starting from scratch. Internal solutions will always mean more time and less product iteration. Unless the problem you’re tackling is core to your business, step back and determine if there’s an external service you can rely on versus building your own. Be smart about leveraging providers; mastering this is pivotal to scaling.

You don’t have to address every shortcoming in your tech – at least not immediately. Picking which problems you want to solve and setting boundaries around those you don’t want to pursue are equally important. Different organizations are going to pick different battles to fight, and ClickUp is no different. Our product isn’t perfect – it’s likely that yours isn’t either – but the important thing is that you continue to iterate and update, improving your customers’ experience at every step of the journey.

Put simply: focus on iterative and pragmatic platform development, not big bangs.

Conclusion

Every company’s growth story is different, but the scaling problems that leaders and their engineering teams face often rhyme. By focusing on the people, processes, product, and platform at the center of your hyper-growth journey, you can pragmatically scale your teams, keep customers happy, and focus on product improvements that matter most.

MMS • Ben Linders

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Returning to testing after having become a test manager can be challenging. For Julia María Durán Muñoz it meant finding a company that appreciated her experience and recognized her desire and ability to do technical work. It can help to get training to update your knowledge, refresh your technical skills, and practice your skills before starting interviews.

Durán Muñoz presented her journey of returning to her origins as a tester after being a testing manager at the Romanian Testing Conference 2022.

Durán Muñoz started her professional career as a programmer for a company in Madrid. She got into testing by chance, when a position for a tester appeared in her hometown.

With testing she discovered her passion:

I was the only tester and over time more people joined the team, whom I trained. I ended up leading the testing team that reached 65 people and growing.

She decided to return to start working as a tester again after being a test manager, aware that the work she did was more related to managing people and dealing with the client than to testing:

Although I like managing teams and helping people grow, I felt I had a lot of ideas to put into practice working on a more technical profile.

Knowing that the world of testing had changed, Durán Muñoz knew she had to catch up. She did training to update her knowledge in testing and recover her programming skills to be able to perform tasks related to test automation. She listened to what others were doing- those who worked doing the tasks that she aspired to do after the transition. She also participated as a tester in some of the projects that she was leading to gain experience.

She expected some challenges getting back in a technical position given her age. It turned out that it wasn’t about her age, but rather about finding a company that really appreciated the experience she had, and her ability and desire to return to a technical profile.

Recovering her knowledge of testing and her programming skills turned out to be difficult for her, but she managed:

It has been a matter of working hard and seeking support from people who had the knowledge, experience and could guide me.

InfoQ interviewed Julia María Durán Muñoz about her journey going back to testing.

InfoQ: What did you learn while being a test manager?

Julia María Durán Muñoz: One of the main things I learned as a testing manager was how to deal with the people on my team and with clients. I learned how important it was for the people on your team to be happy so that the results are as expected.

I also learned the importance of listening and the difference in results obtained depending on how you communicate things. The manager has to be an example and be able to transmit the passion for a job well done.

InfoQ: How did people respond in interviews regarding switching from a manager to a technical position?

Durán Muñoz: I got all kinds of reactions: from suspicion and thinking that it would be something temporary and that after a while I would want to be a manager again, to those who shared my point of view, agreeing with me that they are two different professional careers and applauding me for being brave enough to look for a job change that would make me happier.

InfoQ: What is your current job like?

Durán Muñoz: I’m very happy. I find myself in a continuous learning environment, which was what I was looking for, in which I can experiment and propose new things. I’m surrounded by colleagues from whom I learn a lot every day. I’m very excited and highly motivated.

InfoQ: What’s your advice to people who would like to find a senior technical position?

Durán Muñoz: Go for it! We really spend many hours a day dedicated to something that does not make us happy. I’m here for anyone who wants to make the change and may need help or guidance in the process.

MMS • Claudio Masolo

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Google’s new Machine Learning Guided Optimization (MLGO) is an industrial-grade general framework for integrating machine-learning (ML) techniques systematically in a compiler and in particular in LLVM, an open-source industrial compiler infrastructure that is ubiquitous for building mission-critical, high-performance software.

The Google AI Blog explored the release.

Compiling faster and smaller code can significantly reduce the operational cost of large datacenter applications. The size of compiled code matters the most to mobile and embedded systems or software deployed on secure boot partitions, where the compiled binary must fit in tight code-size budgets.

In a standard compiler, the decisions about the optimizations are made by heuristics, but heuristics become increasingly difficult to improve over time. Heuristics are algorithms that, empirically, produce reasonably optimal results for hard problems, within pragmatic constraints (e.g. “reasonably fast”). In the compiler case, heuristics are widely used in optimization passes, even those leveraging profile feedback, such as inlining and register allocation. Such passes have a significant impact on the performance of a broad variety of programs. These problems are often NP-hard and searching for optimal solutions may require exponentially increasing amounts of time or memory.

Recent research has shown that ML can help with these tasks and unlock more code optimization than the complicated heuristics can. In real code, during the inlining phase, the compiler traverses a huge call graph, because there are thousands of functions calling each other. This operation is performed on all caller-callee pairs and the compiler makes decisions on whether to inline a caller-callee pair or not. This is a sequential decision process as previous inlining decisions will alter the call graph, affecting later decisions and the final result.

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a family of ML techniques that may be applied to find increasingly optimal solutions through an automated iterative exploration and training process. MLGO uses RL to train neural networks to make decisions that can replace heuristics in LLVM. The MLGO framework supports only two kinds of optimizations: inline-for-size and register-allocations-for-performance.

The MLGO framework is trained with the internal Google code base and tested on the code of Fuchsia — a general-purpose open-source operating system designed to power a diverse ecosystem of hardware and software where binary size is critical. For inline-for-size optimization, MLGO achieves a 3% to 7% size reduction. Similar to the inlining-for-size policy, the register allocation (regalloc-for-performance) policy, MLGO achieves up to 1.5% improvement in queries per second (QPS) on a set of internal large-scale datacenter applications.

This framework is still in a research phase. Google says its future goals are to expand the number of optimizations and apply better ML algorithms.

MMS • Sergio De Simone

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

OpenSSL 3.0.4, released less than a month ago, introduced a bug that enabled a remote code execution vulnerability on machines computing 2048 bit RSA keys on X86_64 CPUs. A fix is now available in OpenSSL 3.0.5.

SSL/TLS servers or other servers using 2048 bit RSA private keys running on machines supporting AVX512IFMA instructions of the X86_64 architecture are affected by this issue.

As Guido Vranken explains, the OpenSSL 3.0.4 release included a fix for a bug affecting four code paths: RSAZ 1024, RSAZ 512, Dual 1024 RSAZ, and Default constant-time Montgomery modular exponentiation. This bug had no security implications, but its fix was applied incorrectly to the dual 1024 RSAZ path due to a wrong argument being passed into a function. This caused a heap buffer overflow, i.e., accessing memory outside of the expected bounds, which could be exploited to corrupt memory.

As a consequence of that, the RSA implementation of 2048 keys was broken and the heap overflow could be triggered by an attacker, for example, when doing a TLS handshake. An exploit could then disrupt services, steal or alter confidential information, and execute arbitrary code, although only DoS could be performed trivially.

I want to note that each of these except DoS are speculative and not trivial to perform, and are predicated upon meticulously controlling the regions that are overread and overwritten by way of influencing the state machine flow, though automatic exploit generators based on symbolic execution reportedly do exist.

According to Vranken, the vulnerability had a potential for being worse than Heartbleed, although a number of factors concurred to reduce its gravity, including the fact that many people have not upgraded to OpenSSL 3. Above all, it only impacted X86_64 CPUs with AVX512IFMA SIMD capabilities.

As mentioned, the fix for this vulnerability is included in OpenSSL 3.0.5, which can be downloaded from the OpenSSL site or GitHub. A workaround is also available for users of OpenSSL 3.0.4, which consists in disabling AVX512IFMA by setting OPENSSL_ia32cap=:~0x200000 in your execution environment.

MMS • Nicky Wrightson

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Key Takeaways

- Staff+ roles are a significant shift away from delivery towards enabling others to deliver better. We need to understand those enablement patterns to be able to start behaving in that manner if we are looking to pursue these roles.

- Staff+ roles are the technical roles beyond senior engineer, and they are not a one-size-fits-all role and there are several archetypes that you will satisfy at different times.

- Staff+ engineers are force multipliers through a variety of channels: support, mentoring and coaching. How can we do that more effectively?

- Staff+ is generally about technical leadership versus deep individual contribution where you transition from delivering brilliantly to enabling others to deliver at their best.

- Transitioning to that next staff+ role, you need to understand what is expected by the company from this role, either through career frameworks or your manager.

In the article, I will describe my views and observations on how staff+ engineers transition to supporters, enablers and force multipliers of others and what technical leadership looks like away from the management track. I will explain the benefits for organisations to have leadership roles that are focussed on technical enablement and support.

Throughout this article “staff+” is referenced – what is meant by this is roles that are beyond the senior engineer role but on the technical track, rather than the management track. This can encompass staff, senior staff, principal and even distinguished or fellow engineers. How many of these levels depends on the size of the organisation. The normal step up from senior engineer is to staff, but smaller organisations may only have principal engineers. This article is centred around the transition into these roles, rather than the specifics of how each level differs.

Staff+ role is such a different role from a senior engineer; it’s a transitory role into technical leadership and enablement of others. However, the traits and behaviours to be successful in this role are often not obvious to people, as we brand these roles as “individual contributor” roles. This categorisation leads to some confusion about how these roles differ from a senior engineer.

What is a Staff+ Engineer Role?

There is no single shape for this role, and it will vary from company to company. Often, companies add this role for career progression and retention of engineers, but without recognizing that in the true sense this should be a role change, not an extension of being a senior engineer.

To help illustrate what I believe the role should look like, it is useful to set the context of why the role might be needed at a company. There has been a move to autonomous teams that have complete end-to-end ownership of a product or value stream. With this, there has been a move away from directional leadership and up-front architectural definition. Teams are now not only accountable for how to build their software, but also how to run and maintain it. Architecture and best practices are now the responsibility of teams. This has led to less coupling, however, they are only one team of many in an organisation that must function together to achieve company goals. Additionally, this comes with an increase in cognitive load as engineers are expected to master more than just the code they write.

This is where the staff+ role comes into play. They enable the teams to do their job better by having a longer and wider view of the technical landscape that the teams are operating in, which they then feed back to the teams. This might be around rolling out or improving cross-cutting concerns, such as CI/CD or monitoring or business-focused initiatives that touch on many areas of the business. Additionally, staff+ engineers should be expected to nurture and grow the teams from a technical angle. Staff+ engineers are highly experienced engineers that have been exposed to a variety of scenarios which they can use to mentor and grow the engineers.

Ashley Joost, principal engineer at Skyscanner, once described it to me as “We’re the coaches”.

Wil Larson wrote about several archetypes of this role in his book: Staff Engineer: Leadership beyond the management track, claiming that there are four archetypes:

- The Tech Lead guides the approach and execution of a particular team. They partner closely with a single manager, but sometimes they partner with two or three managers within a focused area. Some companies also have a Tech Lead Manager role, which is similar to the Tech Lead archetype but exists on the engineering manager ladder and includes people management responsibilities.

- The Architect is responsible for the direction, quality, and approach within a critical area. They combine in-depth knowledge of technical constraints, user needs, and organization level leadership.

- The Solver digs deep into arbitrarily complex problems and finds an appropriate path forward. Some focus on a given area for long periods. Others bounce from hotspot to hotspot as guided by organizational leadership.

- The Right Hand extends an executive’s attention, borrowing their scope and authority to operate particularly complex organizations. They provide additional leadership bandwidth to leaders of large-scale organizations.

These archetypes are not fixed and in fact, I have found myself floating between several of them in a single organisation as per what I was working on.

For example, I was working on the data platform at Skyscanner consolidating the approach for capturing user behavioural data from the website. This was much more the architect’s role, but in rolling out that work I also got deeply concerned with data observability and data quality. We were relying more and more on custom data point emissions from unreliable sources such as apps. By talking to end-users and data emitters, I saw a massive gap in our visibility and feedback loop over the quality of the data that we were using to drive business decisions. This is where I found myself moving into more of a solver archetype. Data quality may on the surface sound binary – “it’s good” or “it’s not good” – the more you look at it, the more nuanced it gets as different consumers have different views on quality. I dug deep into the topic, and in collaboration with a product manager we brought a data quality strategy to the table. At this point, my archetype changed once again towards the tech lead as we started to staff the initiative. In this role, I was charged with getting others up to speed in the problem space and providing a guiding hand towards some steps forward in addressing the issues that had surfaced.

Force Multiplying by Enabling Others

Staff+ engineers enable organisations to scale whilst maintaining and building a culture of quality execution. This is by moving from excelling at engineering ourselves, to also getting others to that level and teaching them to also pay it forward via a culture of enabling and supporting others. The growth of others is the cornerstone of the role and enables a higher degree of autonomy for teams which in turn allows for better product delivery.

Certain behaviours become critical for staff+ engineers to exhibit in order to become enablers. They should be heavily invested in driving constant improvement in quality, quantity and value of engineering output by support rather than direction via:

- Mentoring and coaching at both the individual level and the larger settings, such as squads/guilds/interest groups

- Collaborating with squads and product managers to define vision, strategy and the execution path

- Identifying opportunities for individuals and teams – taking the coach position rather than the star player in interesting work

- Identifying/unblocking & reducing dependencies – providing cross-team communication and high-level thinking

- Identifying possible improvements whether it be technical or process and influence the execution

- Instilling the benefits of self-reflection and constant improvement

- Fostering a safe environment and trusted relationships to encourage innovation

- Encouraging and promoting process change

- Providing the space and opportunity for growth

- Protecting engineers’ precious time from distraction or stress

- Being trusted by squads to soundboard ideas, frustrations and worries

- Coaching the squads to understand the value of consistency, observability and quality

- Acting as champions for squads and individuals, especially where their voices may not be heard

Technical Leadership on the IC path

IC or individual contributor path is where the staff+ engineer role tends to reside – senior engineers can choose between the management path and the “IC” path. However, I think this terminology further muddies a more universally accepted definition for the staff+ roles. Actually, this whole path definition adds to the confusion.

The management path is about the people aspect, therefore it could be seen that the “IC” is individually contributing and not about people. However, this is so incredibly damaging for the understanding of these roles – it is ALL about the people. It’s all about the people and leadership – how we help grow others through our depth of experience. Staff+ are there to provide leadership and guidance through influence. The influence goes up and down the ladder – influencing less technical yet more senior stakeholders towards the right strategy, but also influencing teams to think about the things that will enable more success for them and their product.

Pat Kua talks of the trident model of career development as in the three spikes of a trident referencing management, technical leadership and individual contributor rather than the typical two-track representation you commonly see (management and individual contributor). In my experience, this trident model is a much fairer and more accurate evaluation of the most successful staff+ engineers I have come across, with the staff+ engineers slotting into that technical leadership bracket.

Technical leadership is a distinctively different path from the IC path. The IC folk will typically spend 80-90% of their time on delivery – think technical domain experts who are exceedingly deep in a technical problem space. The technical leadership path though is where the staff+ engineers reside. They are looking forward to how to get teams and individuals to own the vision and strategy, coaching them to give them the skills to continuously improve the execution towards those common goals.

Supporting Others

Part of the role of enablement and leadership comes through the support you can provide. Support can come in the form of coaching, knowledge transfer and being the voice for those either not able to be heard or aren’t in the room. Additionally, support comes from proactively identifying areas that could improve the engineers’ lives.

I start by exploring the pain points for teams and individuals to drive the best way in which I can help them. Sometimes there is a technical solution – a very common gripe is something around deployment, for example, speed or automation. These problems are often cross-cutting and it takes a staff engineer to be able to push for these changes to be prioritised. Sometimes the problems are organisational or people-based. For these types of problems, the type of support from a staff+ engineer might be to purely provide a safe space or to use their influence and network to bring these problems out into the open.

Staff+ engineers are highly experienced engineers – they have seen a lot of problems and have felt the pain of operating and maintaining systems. Where this is useful is to coach teams and individuals with their problems. Often when a problem space is still super murky or complex, staff+ engineers can provide feedback on approaches. The great staff+ engineers do this without directionally exerting their experience, but instead coach others towards a better solution or approach. It can be hard especially if you are unable to steer teams toward your solution. My rule of thumb is that if I can’t influence a team in the direction I think is best, then either my influence needs work or the team knows better than me. The important part is to ensure mitigations are in place, even if teams want to go in a different direction rather than use authority to influence them back to your way of thinking. Staff+ engineers should be using influence over authority.

How to Get That Staff+ Engineer Role

This is very dependent on organisation but generally, there are two routes into this role: promotion and getting a new role.

However, prior to going down either of these routes, you need to really question whether you want this role – it is a very different role to the senior engineer role, as I explained earlier.

Promotion is definitely the easier route for getting a staff engineer role. However, it is still a substantial job change and could be likened to crossing the chasm for tech adoption. Even if your company has a well-defined career framework, normally the description for staff+ is intentionally vague, for example, “You lead or influence a team in a deep problem space or a number of teams across a broader area”. The reason it is vague is to allow for all the different archetypes described earlier to exist, and equally staff engineers should be proactively identifying what they work on.

To get into this role via moving companies is a much harder proposition as most companies will expect experience in this role prior to giving this role to someone. However, if you are demonstrating the behaviours I listed above as a senior in a large company, that can be ported over to a smaller company as a staff+. Alternatively, going for lead roles in small companies could line you up nicely to get the staff+ when the company scales enough to warrant it. When going for this role at another company, make sure you are aligned with them on what the role involves and what the expectations are. A career framework is really helpful here. Don’t assume that everyone thinks the same as you about this role because there is a significant disparity in thinking about this role. Spend time speaking to the company about what the expectations are for you when you join.

Either getting promoted or getting this role at another company will involve having evidence that you are able to do this role. This invariably means getting evidence of already performing this role. There is a concept called the “staff engineer project,” which is a piece of work that seniors do that provides that needed evidence. Staff+ engineers are expected to work in murky problem areas – areas that are poorly understood, have a high level of complexity, perhaps distributed over a wide set of stakeholders or very early in its definition. Senior engineers have been known to seek out projects or fabricate problems to demonstrate evidence of working at the staff+ level. This might be due to not having access to problem spaces that fulfil the requirements for evidence for a staff+ role through their normal work for one reason or another. These “staff engineer projects” can be very effective in helping a promotion process but equally, they should be employed with caution. I have seen these projects passed on to teams to support after the promotion has to been given out, despite the team never agreeing to the building of this project.

There are three core aspects that you can centre your evidence around:

- Company values – how are you demonstrating living the company values?

- Career framework – what are the company expectations of you in this next role? Strategically plan how to achieve this. If a company doesn’t have a career framework, then how are you able to measure how close you are to being ready for promotion, and equally, how can you measure your effectiveness once in that role?

- Supporting witnesses – having people who are working in the role already providing evidence of working at a higher level is very powerful. Equally, if you have a sponsor they should be able to help you champion your cause.

Conclusion

The staff+ role is not an extension of being a senior engineer. Before going for the role, be crystal clear about why you want it. The role centres more around people than it does around code. Really question if this role is for you: whether you love being hands-on in a problem space or if you get excited about working with others to help them deliver.

To be successful in this role, you have to become an enabler by providing technical support, guidance and a safe space for the teams. Additionally, you should be looking for ways in which you can improve the autonomy and focus of your teams by identifying blockers or improvements that can be made. The best way to do this is to identify the pain points your teams are feeling and see how you can prioritise the work to resolve or minimise them.

As a staff+ engineer, you should be bringing the wider context to the teams to avoid them repeating work that could be done more efficiently as cross-organisation initiatives. This will allow the engineers to focus on delivering business value for their domain.

At the core of this role is influence. You need to be able to influence engineers without diminishing their autonomy. You also need to influence those above and those who are outside of engineering to get change prioritised. Most importantly, your influence can provide others with opportunities that will help them grow in a safe environment. This makes the role a tough jump up from senior engineer and is a skill that, like coding, takes practice to master.

MMS • Steef-Jan Wiggers

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

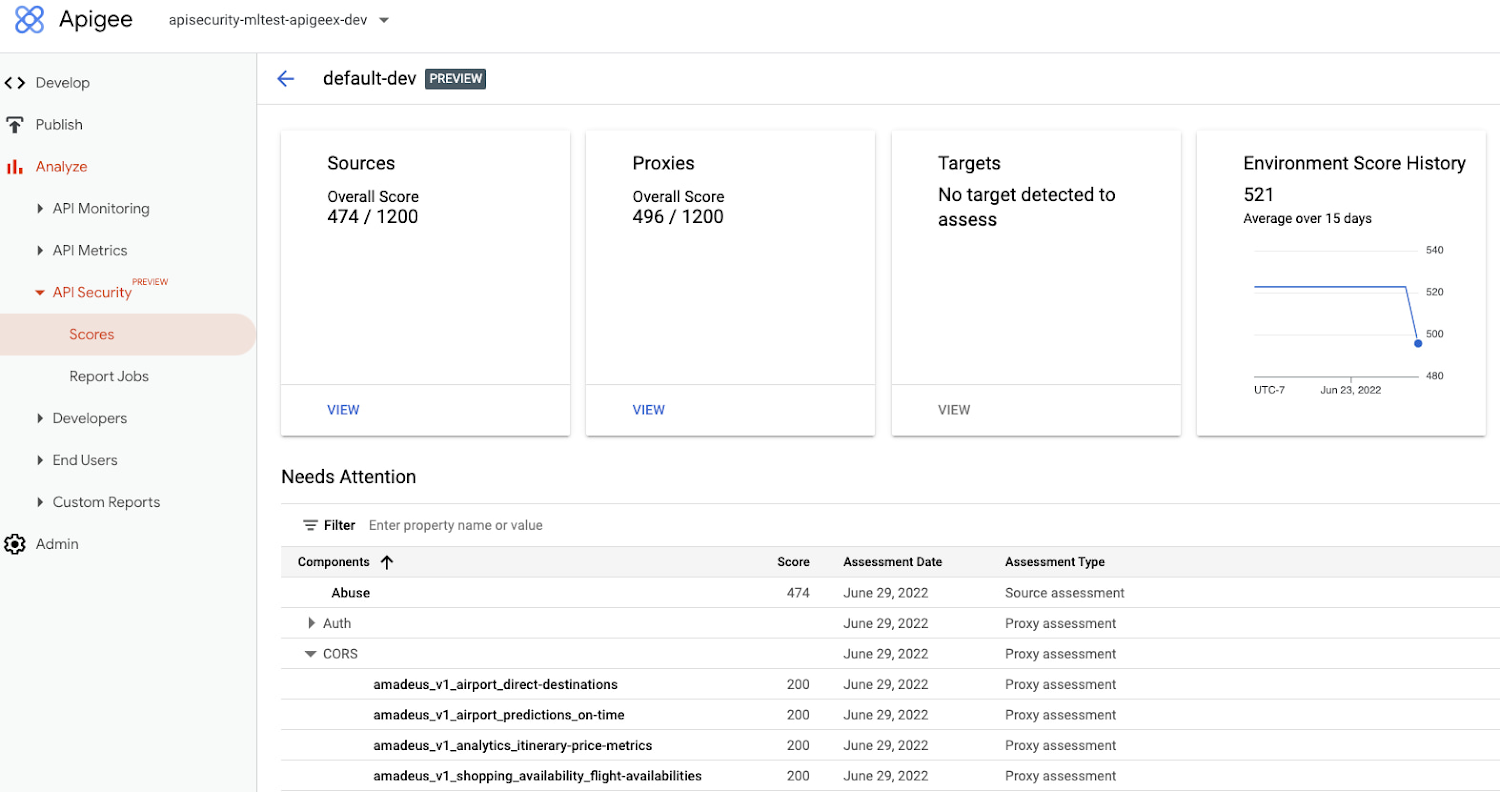

Recently Google announced the public preview of Advanced API Security, a comprehensive set of API security capabilities built on Apigee, their API management platform. With the new capability, customers can detect security threats more efficiently.

The company acquired Apigee in 2016, integrating the startup’s cloud-based API creation and management platform into a service available for Google Cloud Platform customers. Subsequently, more capabilities and features were added to the service, such as monitoring capabilities and more security enhancements with the integration of Cloud Armor and Cloud Identity and Access management. The latest addition is Advanced API Security.

Vikas Anand, a director of product at Google Cloud, explains in a Google Cloud blog post:

Advanced API Security can make it easier for API teams to identify API proxies that do not conform to security standards. To help identify APIs that are misconfigured or experiencing abuse, Advanced API Security regularly assesses managed APIs and provides API teams with a recommended action when configuration issues are detected.

Advanced API Security capability in Apigee specializes in detecting bots and identifying API misconfigurations. When it detects configuration issues, the service assesses managed APIs and recommends actions, and it uses pre-configured rules to identify malicious bots within API traffic. Each rule represents a specific type of unusual traffic from a single IP address; if an API traffic pattern matches any of the rules, Advanced API Security flags it as a bot.

Google brings the Advanced API Security to respond to increasing API-driven attacks. According to a recent Cloudentity study, 44 percent of companies have experienced significant API authorization issues involving privacy, data leakage, and object property exposure with internal and external-facing APIs. Companies like LinkedIn, Peleton, Marriott, and Parler have fallen victim to API-driven attacks within the last few months. Gartner forecasts that APIs will be the most common point of attack this year.

In a LinkedIn blog post, tech influencer Evan Kristel wrote:

APIs are challenging to protect. Traditional solutions can’t handle the complexities of the API ecosystem. Attackers know this, which is why they focus on APIs.

Furthermore, Google is also facing more competition in the API security segment with newly API-focused cybersecurity products such as Salt Security, Noname Security, and Neosec. At the same time, established vendors like Barracuda, Akamai, and Cloudflare have expanded their offerings.

Lastly, Advanced Security API is free of charge during the public preview.

MMS • Susanne Kaiser

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Subscribe on:

Welcome and Introduction [00:04]

Wes Reisz: Domain-Driven Design is an approach to modeling software focused on a domain, or a logical area that defines a problem that you’re trying to solve. Originally popularized in the early 2000s by Eric Evans, DDD’s focus on making software a reflection of the domain it works with has found a resurgence in the isolation and decoupled nature, or at least the promise of it, with microservices. Wardley Maps is a strategic way of visualizing a value chain or business capabilities in the grid characterized by a spectrum towards commodity on one axis, and most commonly something like visibility on another axis. It helps you understand and makes important strategic decisions such as like a build versus buy decision. Finally, team topologies is an approach to organizing business and technology teams for fast flow. It’s a practical kind of step-by-step adaptive model for organizational team design interaction.

When combined, Domain-Driven Design, Wardley Maps, and team topologies provides a powerful suite of tools to help you think about modern software architecture. My name is Wes Reisz, I’m a principal technologist with Thoughtworks and co-host of The InfoQ podcast. Additionally, I chair the QCon San Francisco Software Conference happening in October, and November this year. Today on the InfoQ podcast, we’re talking to Susanne Kaiser. Susanne is an independent tech consultant, software architect, and an ex-startup CTO who has recently been connecting the dots between Domain-Driven Design, Wardley Maps, and team topologies. She recently gave a fantastic talk at QCon London diving into the intersection of the three. So on today’s show, we like to continue the conversation talking about Domain-Driven Design, Wardley Maps, and team topologies. We’ll first tap the recap three, and then we’ll dive into some of the success stories and some of the understanding that Susanne has when she’s talking to the folks about the consulting work. As always, thank you for joining us on your jogs, walks and commute. Susanne, thank you for joining us on the podcast.

Susanne Kaiser: Thank you so much for having me, I’m looking forward to it.

Wes Reisz: Okay. We talked about Domain-Driven Design, Wardley Maps, and team topology in the introduction, at least I did like a high level overview. Anything you want to add to the overview that I kind of gave?

Susanne Kaiser: No, it was a great overview. So I like to hear, to listen to stories that other bring into the table because whenever I make the introduction that it’s like, oh yeah, it’s so either going too far into details. And then the podcast host, they then tend to bring very great summaries, so nothing to add. Great introduction.

What made you bring together Team Topologies, Domain-Driven Design, and Wardley Map? [02:30]

Wes Reisz: Great. There’s so many things that are in software. What made you decide to bring these three things together to kind of a story?

Susanne Kaiser: Yes. So for me, the combination of Wardley Mapping, Domain-Driven Design and team topologies evolved naturally over time, but it was at its core driven by system thinking. So, Dr. Russell Ackoff, one of the pioneers of the system thinking movement, he stated that a system is more than the sum of its parts. It’s a product of their interaction. So the way parts fit together, that determines the performance of system, not on how they perform taken separately. So, and when we are building systems in general, we are faced with the challenges of building the right thing and building the thing right. Right? And building the right thing addresses effectiveness, and addresses questions such as how aligned is our solution to the users and business needs. Are we creating value for our customers? Have we understood the problem and do we share a common understanding and building the thing right?

Focuses on efficiencies, for example, efficiency of engineering practices, and it’s not only crucial to generate value, but also being able to deliver that value. How fast can we deliver changes, and how fast and easy can we make a change effective and adapt to new circumstances. So, the one doesn’t go without the other, but as Dr. Russell Ackoff pointed out doing the wrong thing right is not nearly as good as doing the right thing wrong. So, by considering the whole, and having effectiveness and efficiency in mind to build the right thing right, that we need a kind of like holistic perspective to build adaptive systems. One approach out of many is combining these three perspectives of business strategy with Wardley Mapping, software architecture, and design was Domain-Driven Design, and team organization was team topologies. So, in order to build and design and evolve adaptive socio-technical systems that are optimized for fast flow of change.

Wes Reisz: Yes, absolutely. That really resonates with me, building the right thing and then building the thing right. Those two phrases really resonate with me, a trade-off and understanding what you’re doing and how you’re thinking about these problems. So, where do you start? You have these three things and you start with domain-driven design? Where do you start when you kind of apply these three techniques?

Susanne Kaiser: So, it depends on your context. You can start each of the perspectives. What I like to start with is first analyzing the team situation, regards to their team cognitive load and their delivery bottlenecks that they’re currently facing. So, what of kind of problems do they have right now? Are they are dealing with high team cognitive load because they have to deal with a big ball of mud when you deal with a legacy system which evolved over the time? Are there organized as functional silo teams where handover is involved? Are these large teams or do the teams need to communicate and coordinate with each other when they want to implement and deliver changes? So, this are kind of questions that I like to address first, like analyzing the current situation of your teams. And then the next step is-

How do you talk to teams about cognitive load? [05:32]

Wes Reisz: Let me ask a question before you go there. Let’s talk about cognitive load for a second. How do you get people to understand the cognitive load that they’re under? A lot of teams have been operating in a certain way for so long, they don’t even realize that their cognitive load is so high that they don’t know of any other way. They don’t know how to adapt to that. How do you have that conversation and get people to understand that the cognitive load that they’re seeing is actually a detriment to flow?

Susanne Kaiser: So, there is different aspect that I like to bring into the conversation, for example. So how much time does it need for them to understand a piece of code? How long does it take to onboard new team members? How long does it take to make a change effective and to implement changes and kind of also comes to software quality in teams and in terms of like testing as well. Are there side effects involved that they could not be easily anticipated, and then also bring it back to a Wardley Map itself. So, what kind of components they are responsible for, and if we have our Wardley Map with the value chain matched to the Y axis, and if you use this, your user needs and components that fulfill the user needs directly or facilitating other components in the value chain. And then the evolutions axis going from left to right from Genesis, custom build, product and rental, and commodity.

And the more you are on the spectrum of a left spectrum of your Wardley Map, then you are dealing with high uncertainty, then also unclear path to action. And the components that are located on the right spectrum of your Wardley Map, there you are dealing with mature stable components where you have a more clear path to action. And if your teams are responsible for components that are located on the left spectrum of your Wardley Map, then there’s a potential high cognitive load involved because you need to experiment more, explore more, discover more and applying then merchant and novel practices instead of best and a good practices on the right part.

Wes Reisz: Yes, that really resonated for me in particular, being able to visualize the value chain onto a Wardley Map, and then be able to say things on the left, things that are more towards Genesis require more cognitive load to keep in your mind. Things that are more towards that commodity side, right side, are definitely less. That really resonated to me when you said that. So, I interrupted you, you said step two. Okay. So, that’s step one, applying some things out. What about step two?

Susanne Kaiser: It doesn’t need to necessarily be step two, but one of the steps could be creating a Wardley Map of your current situation and to look at what is your current landscape you are operating in, what are your users, what are the users’ needs? What are the components of fulfill this user needs? And then also to identify the streams of changes in order to optimize for fast flow change, that requires to know where the most important changes in your system are occurring. The streams of changes, and there could be different types of stream of changes. And with the Wardley Map, this visualized activity oriented streams of changes reflected or represented by the user needs. So, if we look at the user needs, these are then the potential stream of changes that we need to focus on when we want to optimize for fast flow of change.

So, that is then first identifying then the stream force changes, the user needs, could be then the next step and using this Wardley Map as a foundation for future discussions, how to evolve then our system. And then we can also go from there to address the problem domain next. And that’s where we are then landing in Domain-Driven Design, and the users and the user needs of a Wardley Map, they are usually representing the anchor of your map, but also constitute the problem domain in regards to Domain-Driven Design. You can then analyze your problem domain and try to distill your problem domain into smaller parts, the sub domains. Different sub domains have different value to the business, so some are more important to the business than others. So, we have different types of sub domains, such as core, supporting and generic. And we can try to identify what are the sub domains that are core, which provides competitive advantage, which tend to change often, which tend to be quite complex and where we should focus on building these parts of our system in-house, because that’s the one that we would like to differentiate ourselves.

So, that requires the most strategic investment so this gives us combined on a Wardley Map, the co-domain related aspects then are then located in Genesis or custom build and needs to be built in-house. Then, supporting a generic that’s then where go to the right spectrum of the Wardley Map, either buying off the shelf product or using open source software for supporting, for example, and then generic, that is something where we can also use go some product and rental, or then commodity and utility where we have can then outsource to, for example, cloud housing services.

Can you give me some examples of bringing these together? [10:17]

Wes Reisz: You’ve used some examples as we’ve talked, let’s try to put this into a journey, like a little example that kind of walks through it. Then as we go through it, I want to ask some questions, things that are about team size, particularly smaller team sizes. When you have a lot of people and large engineering teams, like QCon London had a talk on my track with Twitter that just in the GraphQL API side, they have an enabling team that has 25 engineers just to support the GraphQL side. So, they have a huge team just in one particular area of their API surface, but in smaller organizations, you may not have that kind of depth of talent to be able to pull from. So, as we kind of walk through this, I want to ask kind of drawing on some of that experience you had as a CTO startup, how do you deal with different sizes when you don’t necessarily have huge teams to be able to handle different areas within the platform? So, you used an example I think in your talk, you want to use that as an example? Let’s try to apply this to something. Does an example come to mind?

Susanne Kaiser: In my talk, I was addressing a fictitious example of an online school for uni students, which was at that state, a monolithic big ball of mud, which was run and supported by functional silo teams and running on top of on-premises infrastructure components.

Wes Reisz: Okay. So do you just take this big ball of mud and put it right in the middle of a Wardley Map? How do you start to tease apart those big ball of mud?