Category: Uncategorized

MMS • Ben Linders

Carlos Arguelles spoke about Amazon’s inflection points in engineering productivity at QCon San Francisco, where he explained that shift testing left can help catch issues early. He suggested using guardrails such as code reviews and coverage checks. Your repo strategy, monorepo or multirepo, will impact the guardrails that need to be in place.

When a company is new, it has to move fast, so there are very few guardrails in place. It’s also generally small enough where you know all the people touching a codebase, Arguelles said. As your customer base grows and more and more people depend on your product, it becomes increasingly important to adopt best practices and ensure everybody adheres to them, he added. Those guardrails don’t come for free: they add friction and reduce your ability to move fast in places, so there’s often a tradeoff here.

As a company grows, investing in custom developer tools may become necessary, as Arguelles explained in Inflection Points in Engineering Productivity:

Initially, standard tools suffice, but as the company scales in engineers, maturity, and complexity, industry tools may no longer meet needs. Inflection points, such as a crisis, hyper-growth, or reaching a new market, often trigger these investments, providing opportunities for improving productivity and operational excellence.

The software development life cycle at Amazon starts with an inner developer loop, where an engineer iterates on a piece of code in their own workspace. By default, engineers run unit tests, gather and gate on code coverage and execute various linters every time they create a build, Arguelles said. When they submit a code review, the code review tool runs a number of additional tests on that code.

When those validations pass and the engineer has thumbs up from their reviewer, the code gets pushed to a repo and CI/CD shepherds that code change through various testing stages and increasingly exhaustive tests, including load and performance tests, before finally pushing to production, Arguelles explained:

We expect most of our code changes to reach production within hours of checkin, as all the guardrails should be automated. Once they reach production, canaries further validate the changes.

Finding issues earlier is always better, Arguelles mentioned. And shifting testing left so that you can catch issues in the inner developer loop (pre-submit), and not in the outer developer loop (post-submit) becomes more and more important as your codebase grows:

This is because if a bad piece of code is submitted and merged, it now blocks N developers around you until it’s rolled back or fixed, and as your system grows, so does N.

Shifting testing left is non-trivial because in order for you to effectively and reliably run end-to-end integration tests against unreleased code you need to invest in ephemeral, hermetic test environments, Arguelles said.

One critical decision that Amazon made is that they operate in a multi-repo world, meaning every team has their own micro-repo. This is in contrast with other companies that have gone the route of a monorepo for the entire company (like Google).

Google uses a monorepo where ~100k engineers use a single repo with no branches. Everybody has to be committed to the health of the repo, because the blast radius of a bad code checkin is enormous; you could literally block thousands of people, Arguelles said. Pre-submit end-to-end testing is not just “nice-to-have,” but business-critical.

Amazon, on the other hand, chose to go the route of multirepos, with every team having essentially their own repo, Arguelles mentioned. This acts as a natural blast-radius reduction mechanism: a bad checkin can break an individual microrepo, but there are more guardrails in place to prevent it from cascading into other team’s microrepos.

Arguelles mentioned that there’s unavoidable complexity in large systems. How you choose to do your development determines where in the software development lifecycle you need to deal with that complexity. Neither company was able to avoid it, but they’re tackling it either pre- or post- submit, he concluded.

InfoQ interviewed Carlos Arguelles about guardrails and micro vs mono repo.

InfoQ: How do guardrails at Amazon look?

Carlos Arguelles: For example, when Amazon was a much smaller company in 2009, you could quickly ssh to a production host to investigate an issue, tail logs, etc. Any manual interaction is inherently a dangerous thing to do – imagine you type the wrong command or accidentally press an extra “0” and bring down that host or cause data loss. So we put guardrails such that if you want to run a command on a production host, it needs to be code reviewed and there’s an auditable record of your action.

Another example is you cannot submit code directly to a repo without going through code review and having a thumbs up from another person. Or we now gate on code coverage drops to ensure all code going to production meets a minimum test coverage bar. Tooling like this provides scalable ways to encode and enforce best practices.

InfoQ: What are the implications of working with micro repos compared to monorepo?

Arguelles: This is a place where the two places where I worked, Amazon and Google, differed significantly because of a foundational decision made by both companies decades ago: Google using a monorepo and Amazon micro repos.

This decision impacts guardrails that need to be in place. For Amazon, end-to-end pre-submit testing was “nice-to-have,” but it was not business-critical.

The decision to have micro repos at Amazon did not come for free, though. In a monorepo, every service is naturally integrated, whereas in a multirepo world, you need to coordinate how changes safely cascade from repo to repo.

MMS • Bibek Bhattarai

Transcript

Bhattarai: My name is Bibek. I work at Intel as AI Technical Lead. Our group mostly deals with customers directly. We have firsthand knowledge of what customers are deploying, where they are deploying, and what platform they use, what matrix they really prefer when it comes to deploying the model. Today’s talk in particular, I’m going to focus on this little addition in CPU architectures called AMX, Advanced Matrix Extensions. It’s added from 4th Gen Intel Xeon processors, you can find on the data center.

Basically, I’m going to go into a little bit of a dirty detail into what exactly in AMX, and what makes it really good for matrix multiplication, and why you should be careful in learning how to enable it, and then how to take advantage of it. I break down the whole presentation into four parts. Why should I care? Then, what does it exactly solve? Then, how does it solve it? I will go into a little bit of detail in there. Then, last but not least, how do I leverage it? How do I make sure I am using it, and then I am taking full advantage of it?

What Deep Learning Workloads Usually Run in CPUs?

From our interaction with customers, our collaboration with customers, there is still a lot of the deep learning workloads that still runs on some CPU. This may be because of availability, which is obviously a big issue. GPUs are hard to come by. You might want to use your GPU for something more important, like training large language models. Or some of the models are inherently bound on the memory bandwidth. For whatever reason, there are a lot of the workloads that still makes sense to deploy on CPU rather than using on GPU. Not to be the downer, because everybody’s talking about LLMs, you can really squeeze a lot of performance out of a CPU. This is a number published by Intel when Llama 3.1 was released. It was on the day of release.

Then, this is what you can get. You can get pretty much one token every 20 milliseconds if you compress your model and then deploy it on a 5th-generation Intel CPU server. What I’m going to say here is, for whatever reason, you may be deploying your workloads on CPU, or you may be doing feasibility analysis to see if you can deploy your workload on CPU. If you’re one of those folks, I want to help you understand what is the maximum I can squeeze out of my CPU so that you can make an educated, informed decision on the selection.

GEMMs (General Matrix Multiplication) Dominate the Runtime

What’s the most time-consuming part in all these workloads? There’s a huge compute-bound part, and there’s also a huge memory-bound part in LLM. A lot of the traditional machine learning tasks, traditional deep learning models, they are heavily bound in computation. Whatever the model architecture is, in the heart of the model is what we call GEMM operation. It stands for General Matrix Multiplication. It’s a matrix multiplication. If you are using encoder-only or decoder-only transformer models, around 70% of the runtime is being spent on the GEMM. Same goes for CNN. You can convert your 1D, 2D, 3D CNN into a matrix multiplication operation, and that takes significant amount of time.

For RNN models, you can convert your LSTM gates, GRU gates, into a linear operation, which transmits to the GEMM operation. You get the idea. Basically, whatever model you are running on the surface, eventually what you are doing on the hardware is spending a lot of the cycle doing matrix multiplication. Obviously, it makes sense to go after this huge component if we want to accelerate our workload on CPU.

Let’s do a little exercise on matrix multiplication. I know it seems like a high school math class. I’m sure pretty much every one of you have written matrix multiplication code at some point in your life. If nowhere, probably during preparing for the interview. I did. This is what typical matrix multiplication looks like. You have matrix A, that size, let’s say M by K, M rows, K column. You have another matrix B, that is K by N, K rows, N column, and then you multiply them together. You get a matrix C, M rows, and then N column.

Typically, the first source code you probably wrote for matrix multiplication probably looked like this. You iterate through M, you iterate through N, that basically iterates over every cell on matrix C. For every cell in matrix C, you need to get one row from matrix A, one column from matrix B, and then do the element-wise multiplication, accumulate all of them together into a single value, and then you move to the next cell on matrix C. This is not an efficient algorithm, obviously, because it’s the most naive matmul.

One thing I really want to point out here is, this is really terrible when it comes to cache utilization. I want to reiterate that cache locality is very important. We saw the impact of caching here. I’m sure you are familiar with the hardware caching. When you fetch a data element from matrix, so this matrix is in memory, when you fetch this particular element, it will fetch a bunch of other elements, assuming that you’re going to use them in future. Then, same goes on matrix B. When you fetch this one, it will fetch a bunch of these elements and put it on the L1 cache. Eventually, when doing the matrix multiplication from matrix B, you are only going to use this element, and you got to move to next row. All these elements you just fetched went to waste. You bought it in the L1 cache, they didn’t get used, so they went to waste.

One really easy way to fix this is called loop reordering. It’s surprisingly really easy, and then it’s very efficient. All we did from the last code is we swapped K and N order in the loop. When we do this, we see this consecutive memory access on all matrix A, B, and C. To compute one row in matrix C, you will use this one, and then you do next row, next row, next row, all the way down, and then you are done with one row.

Then, you will switch on A, and then repeat the process on B. There are lots of other ways to make matrix multiplication cache-friendly. For example, tiled matrix multiplication is one of the popular approaches nowadays, especially because of the GPUs and parallelization potential of these tiled matrix multiplication. Basically, when you are doing the matrix multiplication on CPU, whatever tiles you are operating on, you want to bring them as close to your processor as possible, so preferably on L1 cache. You want to bring them in L1 cache. As you can see, this simple decomposition, I decomposed my 1K-by-1K matrix into tile of 128-by-128, and then I used this two-tiered loop, and then it actually reduced the runtime from 130 milliseconds to 89 milliseconds.

Obviously, we’re not going to spend the whole time optimizing the matrix multiplication, because there are literally teams of hundreds of engineers in almost every big company who are working full-time to optimize GEMM kernels. What I want you to take from this little exercise is the fact that data locality is really important. Obviously, with modern CPU architecture, the optimization is much more complicated. The tiling is not cache agnostic. There are multiple tiers of caches. You want to maintain locality in all of them. There are architectures like AVX, which can process huge chunks of data in a single go. You want to take that into consideration when optimizing your algorithm. If you just run this matrix multiplication on NumPy, it runs in around 13 milliseconds. We are still seven-fold away from that optimal solution. NumPy, when you run in CPU, it is just oneMKL from Intel, so you get the idea.

One point I really want to emphasize here is, for better performance, you want to have a large amount of useful data as close to the CPU as possible. You want to have as large amount of data close to CPU, but those large amounts of data have to be useful. It cannot be useless. If you really want to go into detail of what matrix multiplication optimization really looks like, there are a couple of blogs I’ve linked here. I really love them. They have code, illustration, everything, so feel free to go through them.

Low-Precision Computation (Intel AMX)

We got one motivation. We want our computer architecture to be able to handle large chunks of data, and then we want them to keep it really close to the processing unit. The second point I want to emphasize, especially with the rise of deep learning and then large language models, is you must be able to compute efficiently on low-precision data. Meryem from TitanML also emphasized that point as one of the five key takeaways for deploying LLMs. She said quantized models are your friend. You want to use the low-precision numbers. Due to the sheer amount of memory you need, and then the amount of compute you need, you want to be able to store your model parameters, weights, and biases using low-precision data format.

Then, you want to have a compute unit that is able to process this data really efficiently. We got our two objectives, and that’s exactly what Intel AMX fixes. For the data part, we want to have a large chunk of data close to CPU, so we used to have tiles on L1 cache. What’s better than having data on L1 cache? You can now have 2D chunk of data in register. You can load 1 kilobyte of data in single register at a time. You have really large chunks of data close to your processing unit. Then, the next part, you should be able to compute those low-precision computation efficiently. Then, that part is handled by what they call tiled matrix multiplication unit, or TMUL. It is basically a systolic area of Fused Multiply-Add ALUs. You can multiply two elements, and then add with the existing element, and then it gives the result. Systolic area of that FMA unit is what’s in the TMUL.

In order to operate these tiles, and TMUL, they have added the instruction sets in x86, so there are basically three groups of instructions you want to take a look at. One is managing the configuration. You need to be able to load your tile configs, and then store your tile configs efficiently. The second group on the bottom left is for data management. You should be able to clear your tile registers, and then you need one instruction to load the data from memory to tile, and then another instruction that can store the data from tile into main memory. As far as the computation goes on the TMUL, right now it supports int8 and bf16. You can see there are four combinations of int8, basically handling signed and unsigned combination. You can do unsigned to unsigned, unsigned to signed, signed and unsigned, and then signed, signed combination.

Then, last one is for bf16. Some more information on resources specification. You get in total eight of those tiles. You can use all of them to make sure you are processing as much as possible at a time. Each of these tiles have to be configured in a way that they cannot exceed 16 rows, and then they cannot have more than 64 bytes in one row. Basically, maximum size you get is 16-by-64 bytes, so that would amount to 1 kilobyte in total.

Then, depending on the precision of the data you are storing on these, if you are doing int8 matrix multiplication, you get to fit a 16-by-64 int8 chunk in one register. If you are doing bf16, you get a 16-by-32 chunk in your register. Basically, what AMX does now is it gets two 16-by-64 int8 matrix and then multiplies that, and then it stores it into a 16-by-16 int8 matrix. Accumulation happens on int32 so that it does not overflow. Then, same for bf16. It gets 16-by-32 matrix A, and then 16-by-32 matrix B, and then the result will be 16-by-16, this time float32 because you don’t want to overflow your bf16.

AMX Utilization

We understood why, and then what exactly is in the AMX. Now I want to move into how we can use this. We already saw a little bit of instruction set that is available for you to manipulate AMX, but obviously you’re not going to do programming using those commands, so you’re going to have to write in high-level languages. This next section covers that. First of all, you want to check if your CPU has AMX or not. For AMX, you will need at least 4th-generation Xeon processor from Intel. That would be Sapphire Rapids, codenamed, or if you are on AWS, that would be M7i, R7i, C7i instances. Then, you will need Linux kernel at least 5.16, because that’s when the intrinsics for programming AMX were introduced on Linux.

Once you have that, if you do lscpu on your Linux server, you’ll see a bunch of information on the CPU, like cores, cache size available, and a bunch of other information among this. This is the one I want you to check. On the flags field, there are a bunch of other flags. Just to check if you have AMX or not, you need to confirm you have these three flags. AMX-TILE is for tile manipulation, AMX_BF16 and AMX_INT8 are for computing on bf16 and int8. Then, for the power efficiency, AMX is disabled by default when running a bunch of softwares. If your software or if your core section needs AMX, you’ll have to make a system call to ask Linux to let you use the AMX resources. This is usually present on every bit of software that uses AMX.

Basically, you have to do this prctl system call and then ask for this X feature, XTILEDATA. Then, once you get that feature access, you will be able to use AMX in your code. There is a link to the Linux document that you can go and then check for more detail.

Once you ask for Linux kernel to use AMX, the next steps are really straightforward. First thing you want to do is, based on your application, you want to configure the tile. There are a bunch of different things you need to configure. You can see there is a structure on the left. First one is palette_id. It has to be 1 when you initialize the tiles, when you configure the tiles. There is start_row. start-row is basically for fault tolerance. If your matrix multiplication or any of these AMX instruction fail, it has to know where to go back to fetch the data. That’s basically what a start_row does.

Then, there are a bit of a result bit. Those are reserved for future architecture extensions. That’s not relevant right now. Two factors that you really need to configure are these. These are columns byte and then rows. These are basically your tile sizes. You want to make sure how big of a tile you want for each of the register. If you undersubscribe this, let’s say if you only use 8 rows and then 32 bytes, then rest of the 8 rows and then remaining 32 bytes will be filled with 0s when doing the computation so that you can still proceed with the operation. Here’s an example initialization I did for a toy code. Like I said, I set palette_id to 1, start_row to 0.

Then, now we want to compute two int8 matrix and then accumulate them into int32, so matrix A, matrix B, and matrix C. Matrix C will be in tmm0. Matrix A and B will be in tmm1 and tmm2. We want 16 rows on each of those tiles and then 64 bytes. What we have is 16-by-64 matrix A, 16-by-64 matrix B, those are int8. Then, when we multiply those together, we get 16-by-16 int8 matrix. B is basically B transpose. You can think 64 is the common dimension when multiplying the matrix. Actually, it’s happening with dot product, so this seems a little bit of a confusing part.

Once you configure your tiles, next step is you load the data from memory to tile. You can use tile load data intrinsics for that. We load C into register 0, A into 1, B into 2, we get these nice three tiles. Next step is basically doing the computation now. Now you can just use this instruction here, dot-product byte, and then we have signed int, signed int, and then we will do accumulation on the DWORD that is int32. I will go into a little bit of detail over this in a while, but basically you are multiplying two int8 chunks and then getting your result in 32 tile. Under the hood, it’s working like this. Like I said, there is a systolic area of FMA, this is a two-dimensional systolic area of FMA, and then it will propagate the data from tile A, and then tile B, and then tile C, and then basically add to what’s already on tile C while multiplying A and B.

Once you are done with your computation, you will store the result from the tile 0 to C, basically back to memory. We can do one tile to one tile and then get one tile. How does this translate to doing really large matrix multiplication? We basically divide them into a bunch of tiles. If we have matrix A and B, that means that if only one-fourth of A, B, and C fits in one tile, we will do this. We will divide A into four tiles, B into four tiles, and then we will follow a schematic where we load some tiles from matrix A, some tiles from matrix B, and then do the computation and then update the result in C. In reality, we are only using three tiles here. We still have five more tiles, so we can load two more from B and then two more from C and then do a huge computation at the same time.

This is basically the continuation of this one. In our example earlier, we loaded C into tmm0, A into tmm1, and then B into tmm2, and then this is basically showing all the data flow that’s happening in your processing element. Before I move forward with this, I want to emphasize that whatever hardware I just described, it’s present on every single core on the CPU. Every single core will have this added piece of silicon that has T, the tile register that can do the data management, and then the TMUL units that can do the computation. These are the supported combinations for now. As you can see, there is a bf16 on the very top. You can multiply two bf16, accumulate them into float32, and basically all combinations of signed and unsigned int, and you will accumulate on int32 to avoid the overflow. How does this map into our low-precision compute requirements?

Obviously, the default training and inference precision, most of the time, is float32. For float32, we don’t use AMX, we stick with AVX-512. For floating-point 16, there is AMX-FP16 and AMX-COMPLEX that’s coming on new 6th-generation of Xeon. It’s not supported right now. For all the other bf16 and then signed and unsigned integers, you use AMX-BF16 or AMX-INT8. The good thing about this AMX or the TMUL architecture is that it’s extensible. Whenever there is a demand for new precision, for example, FP8 is picking up pace really well, int4 has been really popular in the literature. If you have this low-precision format that becomes really popular, then Intel will add native hardware computation support for those in the next iteration of CPU, and then you get to enjoy them.

How Do I Take Advantage of AMX?

You can do matrix multiplication with this really tedious way. Why would I do this? That’s the question most people ask. Why would I want to do that? This is for how exactly you leverage AMX on your deep learning workload. For this, you don’t really need to do whatever matrix multiplication I just did. If you are someone who is developing a custom operator, custom primitives, like we talked earlier on the TPPs, so if you have new primitives that uses a different form of GEMM, then you might have to implement this on your own, or you can just put in request to Intel’s oneDNN team, and then they’ll do implementation for you. If you are someone who is working on frameworks that is not one of the popular ones, like TensorFlow, PyTorch, ONNX, these frameworks are widely supported by Intel engineers. They push their optimization regularly to those frameworks.

If you are working on one of those frameworks that does not have Intel support, then all you need to do to enable these features on Intel machine is port either oneDNN, oneMKL, and then whatever other libraries that are relevant to your framework. Even for this, if your framework is picking up popularity, then Intel will be more than happy to jump in and then do the integration for you. I don’t see anybody exactly doing this outside of Intel, or maybe AMD, or some other folks who want to enable and maximize the ability of their hardware. For the folks who are either data scientists and ML engineers who rely on framework, all you have to do is install the new enough framework. That’s all you need to do. You have TensorFlow 2.10. After TensorFlow 2.10, it uses oneDNN by default on CPU. If you have a workload running on CPU, make sure you are using newer than 2.10 TensorFlow. Same goes for PyTorch. If you have a workload that is running on PyTorch, you want to make sure it is new enough.

Once you have new enough PyTorch, this is all you need to do. If you want to use AMX_BF16, you just run your workload using Auto Mixed Precision. You run your model using Auto Mixed Precision, and then AMX_BF16 will automatically kick in. There are a bunch of operators that are supported on the oneDNN for bf16 precision. Same goes for int8. If you quantize your model using PyTorch or some other framework, and then you run it using PyTorch, then you are automatically utilizing the AMX_INT8 that’s implemented in oneDNN. Because PyTorch uses oneDNN by default on CPU. Whenever you use framework, AMX gets used whenever possible. If you have your model in bf16, int8, more than likely you are already utilizing AMX_BF16 or AMX_INT8.

The good thing is this works really well with both torch.compile and TorchScript because folks have exported their model into different formats. Intel makes sure that all the torch.compile and then TorchScript exported model supports the AMX kernels. The same goes for TensorFlow. You need to make sure that MAX ISA is AMX_BF16 so that it can use the AMX_BF16. Once you do that, all you need to do is set the AMX flag true. Then you get to enjoy the acceleration without doing anything at all. Obviously, you can quantize your model and run it. The same thing goes here.

For Optimization Freaks

For people who are going to go to the extra mile to get the best performance, so this is where I would say I reside. I want to make sure I can get the best performance I can on the model without losing accuracy. Obviously, I talked about TensorFlow and PyTorch. Intel contributes periodically to this framework. A lot of the optimization that are not yet upstreamed into PyTorch and TensorFlow, more aggressive ones, some that does not meet the Meta or Google’s requirement, they reside on these repositories. Intel Extension for PyTorch, Intel Extension for TensorFlow. As you heard earlier, IPEX was mentioned on AMD’s evaluation as well. It optimizes a lot of the PyTorch workload. Depending on the model, you can get a really huge boost. To compress your model really well, sometimes just converting using PyTorch’s default quantized dynamic does not meet your accuracy requirement because there is a huge accuracy loss when you quantize to low-precision format.

Intel has tools that give you a way to quantize your model, compress your model using sparsity pruning, do distillation, basically make it as small as possible so that you can run efficiently on CPU. Then, these frameworks have a safeguard that allows you to tune for accuracy. You can put in, “I am willing to lose no more than this much accuracy”. Then, they will iterate on your model and then find the config that meets that accuracy requirement and then give you the compressed version of your model.

Then, OpenVINO Toolkit is a little bit different. It has the compression capability, just like Intel Neural Compressor. It’s also an end-to-end system, so you can actually train your model and also deploy your model because it has Model Server as well. If you want really best performance on CPU, I would pay some attention to this toolkit. I know the transformer has been really the focus of a lot of the conversations on this conference, as well as the whole deep learning industry.

Intel Extension for Transformers is a tool that does more or less what Intel Neural Compressor does, but more aggressively for transformer model. You can get lots of improvement on your large language models, embedding models by using the compression techniques that are in this tool. They have a really large amount of examples on how to convert model to bf16, int8, int4, int2, whatever precision you need. I would check this out for some examples.

How Does This Translate to Different Models?

What does this mean? We saw the matrix multiplication. What does this do to actual deep learning model runtimes? These are some of the performance metrics I took over the year from our customer works. These are the models that have been deployed in CPU. Then they were deployed in 3rd-generation Xeon, then they moved to 4th-generation Xeon. We do this analysis all the time to give them the best config they can get to make sure they optimize the performance per dollar.

As you can see, the red vertical line, is the float32 baseline. Just by using AMX_BF16 or AMX_INT8 for accelerating GEMM operations, you can get a really good improvement. For DistilBERT or the BERT base, you get more than 5x improvement just going bf16 with no loss in accuracy. For all these numbers, there is less than 1% loss in accuracy for int8. For bf16, no loss in accuracy. For some of the CNN model or CRNN model, you get more than 10x improvement just by using the new enough framework and then doing the model quantization.

Summary

What is it? It’s an instruction set architecture extension that was introduced on 4th Gen Xeon. It will continue to evolve when we produce more iterations of Xeon. It’s basically a dedicated piece of silicon on each core that has data management unit and then compute unit. What data types are supported? For now, AMX-TILE is for your data management. Then, AMX_BF16 and AMX_INT8 are for doing computation on bf16 and int8 data. On the future iteration of Xeon, AMX-COMPLEX and AMX-FP16 are coming. Then, obviously, how do I use it? Most of the time, just use the framework that already uses oneDNN, OpenBLAS, oneMKL. If you want to go the extra mile and optimize your workload, look into OpenVINO, Neural Compressor, and other tools I just mentioned earlier.

Questions and Answers

Yue: I’m always curious about how the sausage is made. The packaging makes it really easy to use these features, if you’re on one of the libraries or frameworks. Most people probably won’t write a CUDA kernel, but it’s fascinating to learn how you can maximize the hardware performance by doing the right thing in software. What kind of effort went into enabling these hardware features in those libraries that people can easily pick up? What is the process like?

Bhattarai: When it comes to enabling these features in the framework, it’s mostly down to oneDNN and oneMKL to write the efficient kernels. They want to make sure all these operations are really optimal. There are a couple of different level of effort happening. One is obviously, like I said earlier, you want to optimize the uses of AMX resource you have. You want to peel all the tiles you have available and then keep your TMUL unit busy. By doing this, you can get up to 8x more operations per cycle compared to the last iteration of the processors. That’s one part. Then the second part oneDNN library really focused on, is breaking the operation into these tiles really efficiently. When you have a linear operation versus when you have 1D, 2D, or 3D convolution, GEMM looks really different.

Some of the time, some of the GEMM operation will not have all 16 rows because they have a really small dimension in one of the dimensions. Factoring for those things and then putting this safeguard for some of those low utilization use cases is one of the things that does. That actually also translates into how you optimally use AMX. If you have a small enough model, it’s suggested to use really large batch because that way you get to fill the 16 rows in AMX_TILE versus for some of the model, if you just use batch size one, then your GEMM operation becomes GEMM B operation. It will be matrix vector multiplication, and then you will not fill the tile and then that way you will waste a lot of the resources there.

Participant: If we use bare metal versus virtual machines, all those techniques to improve the efficiency of the computation, is there any different considerations we can have when we have bare metal versus Linux?

Bhattarai: On the bare metal, we do have control on all the physical threads as well as Hyper-Threads. Basically, enabling Hyper-Thread might not always help, but it will not do the harm. Same goes for these instances. When you are running on cloud with CPU, you don’t know what the rest of the node is being used for. If there is a way for you to utilize Hyper-Threading, then you can enable Hyper-Thread to get the performance improvement on cloud.

See more presentations with transcripts

Article: Building Reproducible ML Systems with Apache Iceberg and SparkSQL: Open Source Foundations

MMS • Anant Kumar

Key Takeaways

- Time travel in Apache Iceberg lets you pinpoint exactly which data snapshot produced your best results instead of playing detective with production logs.

- Smart partitioning can slash query times from hours to minutes just by partitioning on the same columns you are already filtering on anyway.

- With schema evolution, you can actually add new features without that sinking feeling of potentially breaking six months of perfectly good ML pipelines.

- ACID transactions eliminate those mystifying training failures that happen when someone else is writing to your table.

- The open source route gives you enterprise-grade reliability without the enterprise price tag or vendor lock-in, plus you get to customize things when your ML team inevitably has special requirements that nobody anticipated.

If you’ve spent any time building ML systems in production, you know the pain. Your model crushes it in development, passes all your offline tests, then mysteriously starts performing like garbage in production. Sound familiar?

Nine times out of ten, it’s a data problem. And not just any data problem: it’s the reproducibility nightmare that keeps data engineers up at night. We’re talking about recreating training datasets months later, tracking down why features suddenly look different, or figuring out which version of your data actually produced that miracle model that everyone’s asking you to “just rebuild really quickly”.

Traditional data lakes? They’re great for storing massive amounts of stuff, but they’re terrible at the transactional guarantees and versioning that ML workloads desperately need. It’s like trying to do precision surgery with a sledgehammer.

That’s where Apache Iceberg comes in. Combined with SparkSQL, it brings actual database-like reliability to your data lake. Time travel, schema evolution, and ACID transactions are the things that should have been obvious requirements from day one but somehow got lost in the shuffle toward “big data at scale”.

The ML Data Reproducibility Problem

The Usual Suspects

Let’s be honest about what’s really happening in most ML shops. Data drift creeps in silently: Your feature distributions shift over time, but nobody notices until your model starts making predictions that make no sense. Feature pipelines are supposed to be deterministic, but they’re not; run the same pipeline twice and you’ll get subtly different outputs thanks to timestamp logic or just plain old race conditions.

Then there’s the version control situation. We’ve gotten pretty good at versioning our code (though let’s not talk about that “temporary fix” from three months ago that’s still in prod). But data versioning? It’s still mostly manual processes, spreadsheets, and prayers.

Here’s a scenario that’ll sound depressingly familiar: Your teammate runs feature engineering on Monday, you run it on Tuesday, and suddenly you’re getting different results from what should be identical source data. Why? Because the underlying tables changed between Monday and Tuesday, and your “point-in-time” logic isn’t as point-in-time as you thought.

The really insidious problems show up during model training. Multiple people access the same datasets, schema changes break pipelines without warning, and concurrent writes create race conditions that corrupt your carefully engineered features. It’s like trying to build a house while someone keeps changing the foundation.

Why Traditional Data Lakes Fall Short

Data lakes were designed for a world where analytics required running batch reports and maybe some ETL jobs. The emphasis was on storage scalability, not transactional integrity. That worked fine when your biggest concern was generating quarterly reports.

But ML is different. It’s iterative, experimental, and demands consistency in ways that traditional analytics never did. When your model training job reads partially written data (because someone else is updating the same table), you don’t just get a wrong report, you get a model that learned from garbage data and will make garbage predictions.

Schema flexibility sounds great in theory, but in practice it often creates schema chaos. Without proper evolution controls, well-meaning data scientists accidentally break downstream systems when they add that “just one more feature” to an existing table. Good luck figuring out what broke and when.

The metadata situation is even worse. Traditional data lakes track files, not logical datasets. So when you need to understand feature lineage or implement data quality checks, you’re basically flying blind.

The Hidden Costs

Poor data foundations create costs that don’t show up in any budget line item. Your data scientists spend most of their time wrestling with data instead of improving models. I’ve seen studies suggesting sixty to eighty percent of their time goes to data wrangling. That’s… not optimal.

When something goes wrong in production – and it will – debugging becomes an archaeology expedition. Which data version was the model trained on? What changed between then and now? Was there a schema modification that nobody documented? These questions can take weeks to answer, assuming you can answer them at all.

Let’s talk about regulatory compliance for a minute. Try explaining to an auditor why you can’t reproduce the exact dataset used to train a model that’s making loan decisions. That’s a conversation nobody wants to have.

Iceberg Fundamentals for ML

Time Travel That Actually Works

Iceberg’s time travel is a snapshot-based architecture that maintains complete table metadata for every write operation. Each snapshot represents a consistent view of your table at a specific point in time, including schema, partitions, and everything.

For ML folks, this is game-changing. You can query historical table states with simple SQL:

-- This is how you actually solve the reproducibility problem

SELECT * FROM ml_features

FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF '2024-01-15 10:30:00'

-- Or if you know the specific snapshot ID

SELECT * FROM ml_features

FOR SYSTEM_VERSION AS OF 1234567890

No more guessing which version of your data produced good results. No more “well, it worked last week” conversations. You can compare feature distributions across time periods, analyze model performance degradation by examining historical data states, and build A/B testing frameworks that actually give you consistent results.

The metadata includes file-level statistics, so query optimizers can make smart decisions about scan efficiency. This isn’t just about correctness, it’s about performance too.

Schema Evolution Without the Drama

Here’s something that should be basic but somehow isn’t: Adding a new column to your feature table shouldn’t require a team meeting and a migration plan. Iceberg’s schema evolution lets you adapt tables to changing requirements without breaking existing readers or writers.

You can add columns, rename them, reorder them, and promote data types, all while maintaining backward and forward compatibility. For ML pipelines, data scientists can safely add new features without coordinating complex migration processes across multiple teams.

The system tracks column identity through unique field IDs, so renaming a column doesn’t break existing queries. Type promotion follows SQL standards (integer to long, float to double), so you don’t have to worry about data loss.

-- Adding a feature is actually this simple

ALTER TABLE customer_features

ADD COLUMN lifetime_value DOUBLE

-- Renaming doesn't break anything downstream

ALTER TABLE customer_features

RENAME COLUMN purchase_frequency TO avg_purchase_frequency

ACID Transactions (Finally!)

ACID support allows ML workloads to safely operate on shared datasets without corrupting data or creating inconsistent reads. Iceberg uses optimistic concurrency control: Multiple writers can work simultaneously, but conflicts get detected and resolved automatically.

Isolation levels prevent readers from seeing partial writes. So when your training job kicks off, it’s guaranteed to see a consistent snapshot of the data, even if someone else is updating features in real-time.

Transaction boundaries align with logical operations rather than individual file writes. You can implement complex feature engineering workflows that span multiple tables and partitions while maintaining consistency guarantees. No more “oops, only half my update succeeded” situations.

Building Reproducible Feature Pipelines

Partitioning That Actually Makes Sense

Let’s talk partitioning strategy, because this is where a lot of teams shoot themselves in the foot. The secret isn’t complex: Partition on dimensions that align with how you actually query the data.

Most ML workloads follow temporal patterns, training on historical data and predicting on recent data. So temporal partitioning using date or datetime columns is usually your best bet. The granularity depends on your data volume. For high-volume systems, use daily partitions. For smaller datasets, use weekly or monthly partitions.

CREATE TABLE customer_features (

customer_id BIGINT,

feature_timestamp TIMESTAMP,

demographic_features MAP,

behavioral_features MAP,

target_label DOUBLE

) USING ICEBERG

PARTITIONED BY (days(feature_timestamp))

Multi-dimensional partitioning can work well if you have natural business groupings. Customer segments, product categories, geographic regions, etc., reflect how your models actually slice the data.

Iceberg’s hidden partitioning is particularly nice because it maintains partition structures automatically without requiring explicit partition columns in your queries. Write simpler SQL, get the same performance benefits.

But don’t go crazy with partitioning. I’ve seen teams create thousands of tiny partitions thinking it will improve performance, only to discover that metadata overhead kills query planning. Keep partitions reasonably sized (think hundreds of megabytes to gigabytes) and monitor your partition statistics.

Data Versioning for Experiments

Reproducible experiments require tight coupling between data versions and model artifacts. This is where Iceberg’s snapshots really shine. They provide the foundation for implementing robust experiment tracking that actually links model performance to specific data states.

Integration with MLflow or similar tracking systems creates auditable connections between model runs and data versions. Each training job records the snapshot ID of input datasets, precisely reproducing the experimental conditions.

import mlflow

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

def train_model_with_versioning(spark, snapshot_id):

# Load data from specific snapshot

df = spark.read

.option("snapshot-id", snapshot_id)

.table("ml_features.customer_features")

# Log data version in MLflow

mlflow.log_param("data_snapshot_id", snapshot_id)

mlflow.log_param("data_row_count", df.count())

# Continue with model training...

Branching and tagging capabilities enable more sophisticated workflows. Create stable data branches for production model training while continuing development on experimental branches. Use tags to mark significant milestones, such as quarterly feature releases, regulatory checkpoints, etc.

Feature Store Integration

Modern ML platforms demand seamless integration between data infrastructure and experiment management. Iceberg tables play nicely with feature stores, leveraging time travel capabilities to serve both historical features for training and point-in-time features for inference.

This combination provides consistent feature definitions across training and serving while maintaining the performance characteristics needed for real-time inference. No more training-serving skew because your batch and streaming feature logic diverged.

from feast import FeatureStore

import pandas as pd

def get_training_features(entity_df, feature_refs, timestamp_col):

try:

fs = FeatureStore(repo_path=".")

# Point-in-time join using Iceberg backing store

training_df = fs.get_historical_features(

entity_df=entity_df,

features=feature_refs,

full_feature_names=True

).to_df()

return training_df

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error accessing feature store: {e}")

raise

Production Implementation

Real-World Example: Customer Churn Prediction

Let me walk you through a customer churn prediction system that actually works in production. This system processes millions of customer interactions daily while maintaining full reproducibility.

The data architecture uses multiple Iceberg tables organized by freshness and access patterns. Raw events flow into staging tables, are validated and cleaned, and then aggregated into feature tables optimized for ML access patterns.

-- Staging table for raw events

CREATE TABLE customer_events_staging (

event_id STRING,

customer_id BIGINT,

event_type STRING,

event_timestamp TIMESTAMP,

event_properties MAP,

ingestion_timestamp TIMESTAMP

) USING ICEBERG

PARTITIONED BY (days(event_timestamp))

TBLPROPERTIES (

'write.format.default' = 'parquet',

'write.parquet.compression-codec' = 'snappy'

)

-- Feature table with optimized layout

CREATE TABLE customer_features (

customer_id BIGINT,

feature_date DATE,

recency_days INT,

frequency_30d INT,

monetary_value_30d DOUBLE,

support_tickets_30d INT,

churn_probability DOUBLE,

feature_version STRING

) USING ICEBERG

PARTITIONED BY (feature_date)

CLUSTERED BY (customer_id) INTO 16 BUCKETS

Feature engineering pipelines implement incremental processing using Iceberg’s merge capabilities. This incremental approach minimizes recomputation while maintaining data consistency across different processing schedules.

def incremental_feature_engineering(spark, processing_date):

# Read new events since last processing

new_events = spark.read.table("customer_events_staging")

.filter(f"event_timestamp >= '{processing_date}'")

# Compute incremental features (implementation depends on business logic)

new_features = compute_customer_features(new_events, processing_date)

# Merge into feature table with upsert semantics

new_features.writeTo("customer_features")

.option("merge-schema", "true")

.overwritePartitions()

def compute_customer_features(events_df, processing_date):

"""

User-defined function to compute customer features from events.

Implementation would include business-specific feature engineering logic.

"""

# Example feature engineering logic would go here

return events_df.groupBy("customer_id")

.agg(

count("event_id").alias("event_count"),

max("event_timestamp").alias("last_activity")

)

.withColumn("feature_date", lit(processing_date))

Performance Optimization

Query performance in Iceberg benefits from several complementary techniques. File sizing matters. Aim for 128MB to 1GB files depending on your access patterns with smaller files for highly selective queries and larger files for full-table scans.

Parquet provides natural benefits for ML workloads since you typically select column subsets. Compression choice depends on your priorities. Use Snappy for frequently accessed data (faster decompression) and Gzip for better compression ratios on archival data.

Data layout optimization using clustering or Z-ordering can dramatically improve performance for multi-dimensional access patterns. These techniques colocate related data within files, reducing scan overhead for typical ML queries.

-- Optimize table for typical access patterns

ALTER TABLE customer_features

SET TBLPROPERTIES (

'write.target-file-size-bytes' = '134217728', -- 128MB

'write.parquet.bloom-filter-enabled.customer_id' = 'true',

'write.parquet.bloom-filter-enabled.feature_date' = 'true'

)

Metadata caching significantly improves query planning performance, especially for tables with many partitions. Iceberg’s metadata layer supports distributed caching (Redis) or in-memory caching within Spark executors.

Monitoring and Operations

Production ML systems need monitoring that goes beyond traditional infrastructure metrics. Iceberg’s rich metadata enables sophisticated monitoring approaches that actually help you understand what’s happening with your data.

Data quality monitoring leverages metadata to detect anomalies in volume, schema changes, and statistical distributions. Integration with frameworks like Great Expectations provides automated validation workflows that can halt processing when quality thresholds are violated.

import great_expectations as ge

from great_expectations.dataset import SparkDFDataset

def validate_feature_quality(spark, table_name):

df = spark.read.table(table_name)

ge_df = SparkDFDataset(df)

# Define expectations

ge_df.expect_table_row_count_to_be_between(min_value=1000)

ge_df.expect_column_values_to_not_be_null("customer_id")

ge_df.expect_column_values_to_be_between("recency_days", 0, 365)

# Validate and return results

validation_result = ge_df.validate()

return validation_result.success

Performance monitoring tracks query execution metrics, file scan efficiency, and resource utilization patterns. Iceberg’s query planning metrics provide insights into partition pruning effectiveness and file-level scan statistics.

Don’t forget operational maintenance (e.g., file compaction, expired snapshot cleanup, and metadata optimization). These procedures maintain query performance and control storage costs over time. Set up automated jobs for this stuff – trust me, you don’t want to do it manually.

Best Practices and Lessons Learned

Choosing Your Table Format

When should you actually use Iceberg instead of other options? It’s not always obvious, and the marketing materials won’t give you straight answers.

Iceberg excels when you need strong consistency guarantees, complex schema evolution, and time travel capabilities. ML workloads particularly benefit from these features because of their experimental nature and reproducibility requirements.

Delta Lake provides similar capabilities with tighter integration into the Databricks ecosystem. If you’re primarily operating within Databricks or need advanced features like liquid clustering, Delta might be your better bet.

Apache Hudi optimizes for streaming use cases with sophisticated indexing. Consider it for ML systems with heavy streaming requirements or complex upsert patterns.

And you know what? Sometimes plain old Parquet tables are fine. If you have simple, append-only workloads with stable schemas, the operational overhead of table formats might not be worth it. Don’t over-engineer solutions to problems you don’t actually have.

Common Pitfalls

Over-partitioning is probably the most common mistake I see. Creating partitions with less than 100MB of data or more than ten thousand files per partition will hurt query planning performance. Monitor your partition statistics and adjust strategies based on actual usepatterns, rather than theoretical ideals.

Schema evolution mistakes can break downstream consumers even with Iceberg’s safety features. Implement schema validation in CI/CD pipelines to catch incompatible changes before deployment. Use column mapping features to decouple logical column names from physical storage. It will save you headaches later.

Query anti-patterns often emerge when teams don’t leverage Iceberg’s optimization capabilities. Include partition predicates in WHERE clauses to avoid unnecessary scans. Use column pruning by selecting only required columns instead of SELECT * (yes, I know it’s convenient, but your query performance will thank you).

Migration Strategies

Migrating from legacy data lakes requires careful planning. You can’t just flip a switch and expect everything to work. Implement parallel systems during transition periods so you can validate Iceberg-based pipelines against existing systems.

Prioritize critical ML datasets first, focusing on tables that benefit most from Iceberg’s capabilities. Use import functionality to migrate existing Parquet datasets without rewriting data files.

-- Migrate existing table to Iceberg format

CALL system.migrate('legacy_db.customer_features_parquet')

Query migration means updating SQL to leverage Iceberg features while maintaining backward compatibility. Feature flags or configuration driven table selection enable gradual rollout.

Pipeline migration should be phased. Start with batch processing before moving to streaming workflows. Iceberg’s compatibility with existing Spark APIs minimizes code changes during migration.

Wrapping Up

Apache Iceberg and SparkSQL provide a solid foundation for building ML systems that actually work reliably in production. The combination of time travel, schema evolution, and ACID transactions addresses fundamental data management challenges that have plagued ML infrastructure for years.

The investment pays off through improved development velocity, reduced debugging time, and increased confidence in system reliability. Teams consistently report better experiment reproducibility and faster time-to-production for new models.

But success requires thoughtful design decisions around partitioning, schema design, and operational procedures. The technology provides powerful capabilities, but you need to understand both the underlying architecture and the specific requirements of ML workloads to realize the benefits.

As ML systems grow in complexity and business criticality, reliable data foundations become increasingly important. Iceberg represents a mature, production-ready solution that helps organizations to build ML systems with the same reliability expectations as traditional enterprise applications.

Honestly? It’s about time we had tools that actually work the way we need them to work.

MONGODB ALERT: Bragar Eagel & Squire, P.C. is Investigating MongoDB, Inc. on Behalf of

MMS • RSS

Bragar Eagel & Squire, P.C. Litigation Partner Brandon Walker Encourages Investors Who Suffered Losses In MongoDB (MDB) To Contact Him Directly To Discuss Their Options

If you are a long-term stockholder in MongoDB between August 31, 2023 and May 30, 2024 and would like to discuss your legal rights, call Bragar Eagel & Squire partner Brandon Walker or Marion Passmore directly at (212) 355-4648. MongoDB between August 31, 2023 and May 30, 2024 and would like to discuss your legal rights, call Bragar Eagel & Squire partner Brandon Walker or Marion Passmore directly at (212) 355-4648.

MMS • RSS

Numberly has been using both ScyllaDB and MongoDB in production for 5+ years. Learn which NoSQL database they rely on for different use cases and why.

Within the NoSQL domain, ScyllaDB and MongoDB are two totally different animals. MongoDB needs no introduction. Its simple adoption and extensive community/ecosystem have made it the de facto standard for getting started with NoSQL and powering countless web applications. ScyllaDB’s close-to-the-metal architecture enables predictable low latency at high throughput. This is driving a surge of adoption across teams such as Discord, TRACTIAN and many others who are scaling data-intensive applications and hitting the wall with their existing databases.

But database migrations are not the focus here. Instead, let’s look at how these two distinctly different databases might coexist within the same tech stack – how they’re fundamentally different, and the best use cases for each. Just like different shoes work better for running a marathon vs. scaling Mount Everest vs. attending your wedding, different databases work better for different use cases with different workloads and latency/throughput expectations.

So when should you use ScyllaDB vs. MongoDB and why? Rather than provide the vendor perspective, we’re going to share the insights from an open source enthusiast who has extensive experience using both ScyllaDB and MongoDB in production: Alexys Jacob, the CTO of Numberly. Alexys shared his perspective at ScyllaDB Summit 2019, and the video has been trending ever since.

Here are three key takeaways from his detailed tech talk:

Scaling Writes is More Complex on MongoDB

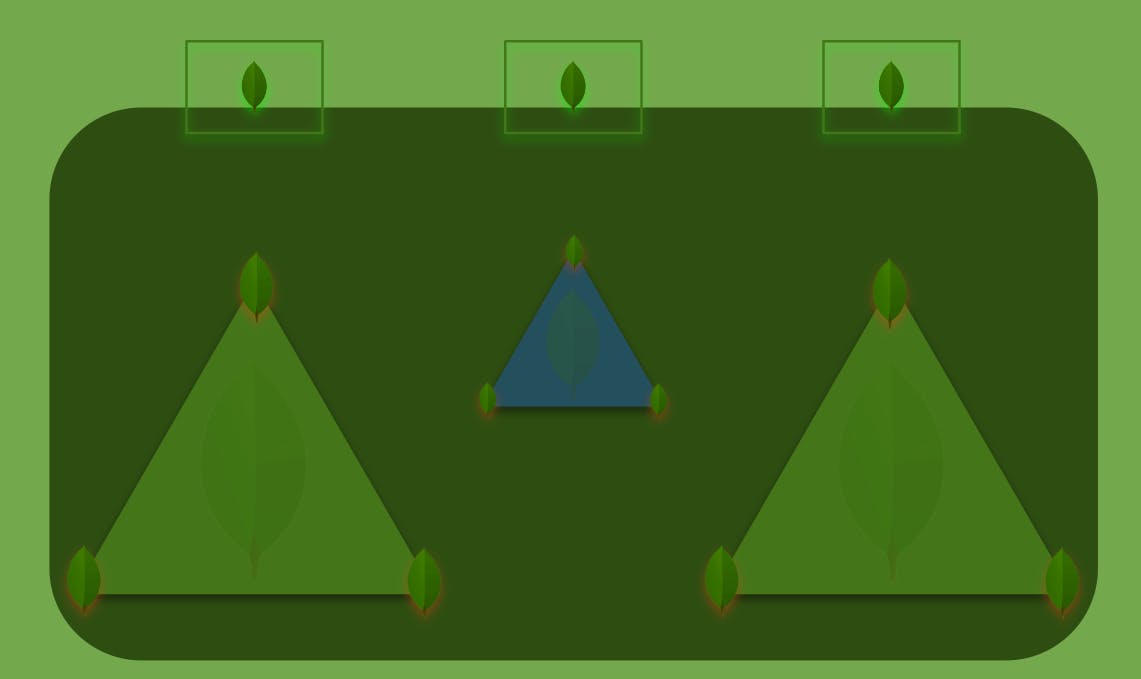

The base unit of a MongoDB topology is called a replica set, which is composed of one primary node and usually multiple secondary nodes (think of hot replicas). Only the primary node is allowed to write data. After you max out vertical write scaling on MongoDB, your only option to scale writes becomes what is called a sharded cluster. This requires adding new replica sets because you can’t have multiple primaries in a single replica set.

Sharding data across MongoDB’s replica sets requires using a special key to specify what data each replica set is responsible for, as well as creating a metadata replica set that tracks what slice of data lives on each replica (the blue triangle in the diagram below). Also, clients connecting to a MongoDB cluster need help determining what node to address. That’s why you also need to deploy and maintain MongoDB’s Smart Router instances (represented by the rectangles at the top of the diagram) connected to the replica sets.

The complexity of scaling writes in MongoDB

Having all these nodes leads to higher operational and maintenance costs as well as wasted resources since you can’t tap the replica nodes’ IO for writes, which make sharded MongoDB clusters the worst enemy of your total cost of ownership as Alexys noted.

For ScyllaDB, scaling writes is much simpler. He explained, “On the ScyllaDB side, if you want to add more throughput, you just add nodes. End of story.”

Alexys tied up this scaling thread:

“Avoid creating MongoDB clusters, please! I could write a book with war stories on this very topic. The main reason why is the fact that MongoDB does not bind the workload to CPUs. And the sharding, the distribution of data between replica sets in a cluster is done by a background job (the balancer). This balancer is always running, always looking at how sharding should be done, and always ensuring that data is spread and balanced over the cluster. It’s not natural because it isn’t based on consistent hashing. It’s something that must be calculated over and over again. It splits the data into chunks and then moves it around. This has a direct impact on the performance of your MongoDB cluster because there is no isolation of this workload versus your actual production workload.”

MongoDB Favors Flexibility Over Performance, While ScyllaDB Favors Consistent Performance Over Versatility

ScyllaDB and MongoDB have distinctly different priorities when it comes to flexibility and performance.

On the data modeling front, MongoDB natively supports geospatial queries, text search, aggregation pipelines, graph queries and change streams. Although ScyllaDB – a wide- column store (a.k.a. key-key-value) – supports user-defined types, counters and lightweight transactions, the data modeling options are more restricted than on MongoDB. Alexys noted, “From a development perspective, interacting with an JSON object just feels more natural than interacting with a row.” Moreover, while MongoDB offers the option of enforcing schema validation before data insertion, ScyllaDB requires that data adhere to the defined schema.

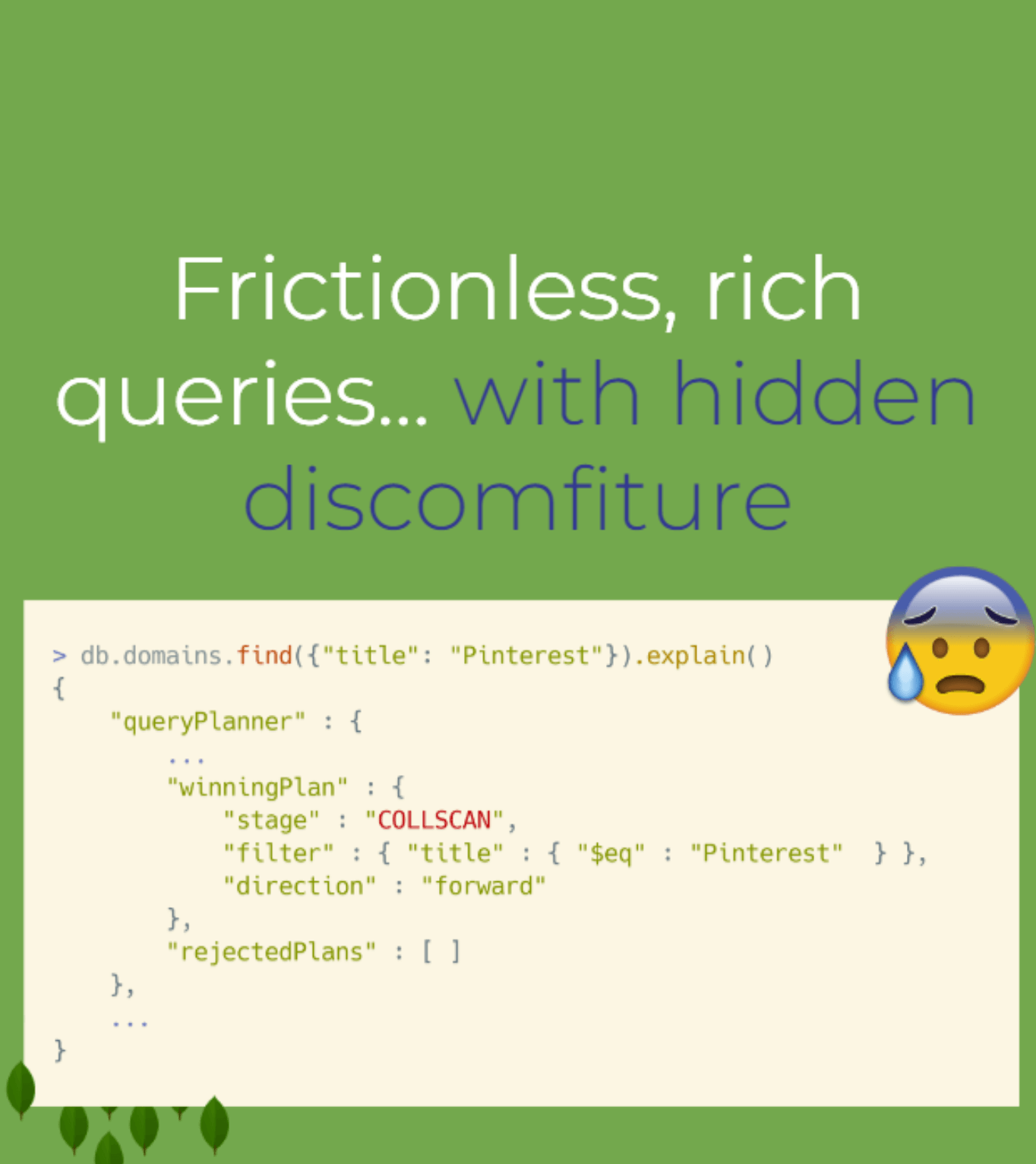

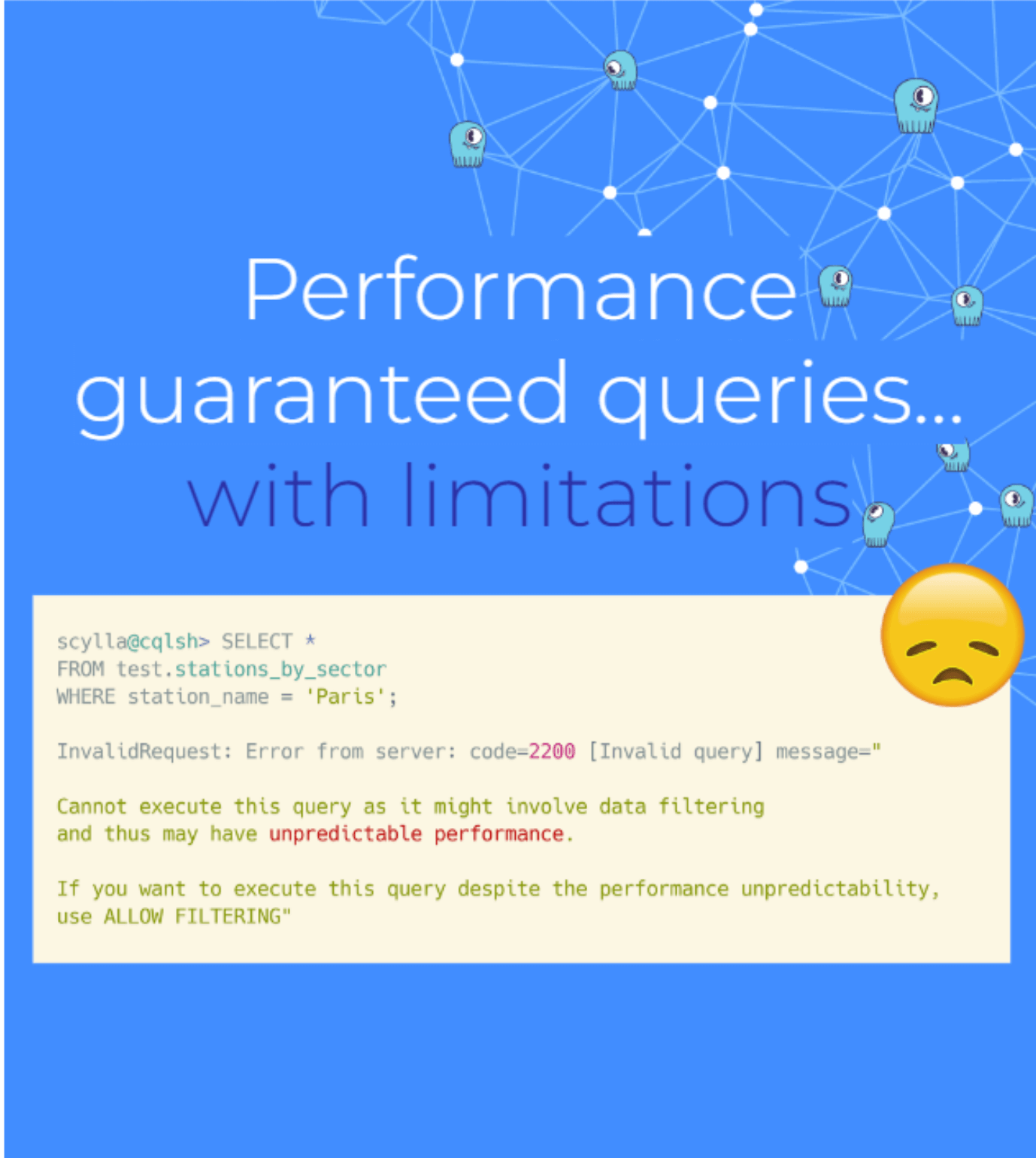

Querying is also simpler with MongoDB since you’re just filtering and interacting with JSON. It’s also more flexible, for better or for worse. MongoDB lets you issue any type of query, including queries that cause suboptimal performance with your production workload. ScyllaDB won’t allow that. If you try, ScyllaDB will warn you. If you decide to proceed at your own risk, you can enter a qualifier indicating that you really do understand what you’re getting yourself into.

Alexys summed up the key differences from a development perspective:

“MongoDB favors flexibility over performance. It’s easy to interact with and it will not get in your way. But it will have impacts on performance – impacts that are fine for some workloads, but unacceptable for others. On the other hand, ScyllaDB favors consistent performance over versatility. It looks a bit more fixed and a bit more rigid on the outside. But once again, that’s for your own good so you can have consistent performance, operate well and interact well with the system. In my opinion, this makes a real difference when you have workloads that are latency- and performance-sensitive.”

It’s important to note that even queries that follow performance best practices will behave differently on MongoDB than on ScyllaDB. No matter how careful you are, you won’t overcome the performance penalty that stems from fundamental architectural differences.

Together, ScyllaDB and MongoDB are a Great NoSQL Combo

“It’s not a death match; we are happy users of both MongoDB and ScyllaDB,” Alexys continued.

Numberly selects the best database for each use case’s technical requirements.

At Numberly, MongoDB is used for two types of use cases:

- Web backends with REST APIs and possibly flexible schemas.

- Real-time queries over unpredictable behavioral data.

For example, some of Numberly’s applications get flooded with web tracking data that their clients collect and send (each client with their own internally-developed applications). Numberly doesn’t have a way to impose a strict schema on that data, but it needs to be able to query and process it. In Alexys’ words, “MongoDB is fine here; its flexibility is advantageous because it allows us to just store the data somewhere and query it easily.”

ScyllaDB is used for three types of use cases at Numberly:

- Real-time latency-sensitive data pipelines. This involves a lot of data enrichment, where there are multiple sources of data that need to be correlated, in real time, on the data pipelines. According to Alexys, “That’s tricky to do…and you need strong latency guarantees to not break the SLAs [service-level agreements] of the applications and data processes which your clients rely on down the pipe.”

- Mixed batch and real-time workloads. Numberly also mixes a lot of batch and real-time workloads in ScyllaDB because it provides the best of both worlds (as Numberly shared previously). “We had Hive on one path and MongoDB on the other. We put everything on ScyllaDB and its sustaining Hadoop-like batch workloads and real time pipeline workloads.”

- Web backends using GraphQL, which imposes a strict schema. Some of Numberly’s web backends are implemented in GraphQL. When working with schema-based APIs, it makes perfect sense to have a schema-based database with low latency and high availability.

Alexys concluded: “A lot of our backend engineers, and frontend engineers as well, are adopting ScyllaDB. We see a trend of people adopting ScyllaDB, more and more tech people asking ‘I have this use case, would ScyllaDB be a good fit?’ Most of the time, the answer is ‘yes.’ So, ScyllaDB adoption is growing. MongoDB adoption is flat, but MongoDB is certainly here to stay because it has some really interesting features. Just don’t go as far as to create a MongoDB sharded cluster, please!”

Bonus: More Insights from Alexys Jacob

Alexys is an extremely generous contributor to open source communities, with respect to both code and conference talks. See more of his contributions at https://ultrabug.fr/

About Cynthia Dunlop

Cynthia is Senior Director of Content Strategy at ScyllaDB. She has been writing about software development and quality engineering for 20+ years.

MMS • RSS

IBM found that the global average cost of a data breach has fallen by 9% compared to 2024, driven by improved detection and containment

Read the original article:

MMS • RSS

SAP SE (SAP) stock rose in its recent intraday trading, following a rebound from the key support level at $285.50. This level represents the neckline of a potential bearish technical formation—a double top pattern developing in the short term. The stock’s rise attempts to recover part of prior losses and relieve its clearly oversold Stochastic conditions, especially as a bullish crossover begins to appear. However, the stock had previously broken a short-term ascending trendline and continues to face negative pressure from trading below the 50-day simple moving average, which increases the likelihood of further losses in the near term.

Therefore, we expect the stock to decline in upcoming sessions, especially if it breaks below the $285.50 support level, which would confirm the validity of the emerging pattern, targeting the initial support level at $269.90.

Today’s price forecast: Bearish.

MMS • RSS

Investment analysts at BMO Capital Markets began coverage on shares of MongoDB (NASDAQ:MDB – Get Free Report) in a research report issued to clients and investors on Monday, Marketbeat Ratings reports. The firm set an “outperform” rating and a $280.00 price target on the stock. BMO Capital Markets’ target price would suggest a potential upside of 16.24% from the stock’s current price.

Investment analysts at BMO Capital Markets began coverage on shares of MongoDB (NASDAQ:MDB – Get Free Report) in a research report issued to clients and investors on Monday, Marketbeat Ratings reports. The firm set an “outperform” rating and a $280.00 price target on the stock. BMO Capital Markets’ target price would suggest a potential upside of 16.24% from the stock’s current price.

MDB has been the topic of several other research reports. Monness Crespi & Hardt upgraded MongoDB from a “neutral” rating to a “buy” rating and set a $295.00 target price on the stock in a research note on Thursday, June 5th. Citigroup cut their price objective on shares of MongoDB from $430.00 to $330.00 and set a “buy” rating for the company in a research report on Tuesday, April 1st. Piper Sandler lifted their price objective on shares of MongoDB from $200.00 to $275.00 and gave the stock an “overweight” rating in a research note on Thursday, June 5th. Barclays upped their price objective on shares of MongoDB from $252.00 to $270.00 and gave the stock an “overweight” rating in a research report on Thursday, June 5th. Finally, Stephens began coverage on MongoDB in a report on Friday, July 18th. They set an “equal weight” rating and a $247.00 price target for the company. Nine investment analysts have rated the stock with a hold rating, twenty-seven have issued a buy rating and one has assigned a strong buy rating to the company. According to MarketBeat, the company has a consensus rating of “Moderate Buy” and an average price target of $281.31.

Check Out Our Latest Stock Analysis on MongoDB

MongoDB Price Performance

MongoDB stock opened at $240.88 on Monday. MongoDB has a fifty-two week low of $140.78 and a fifty-two week high of $370.00. The firm has a market cap of $19.68 billion, a price-to-earnings ratio of -211.30 and a beta of 1.41. The firm has a fifty day moving average price of $208.62 and a two-hundred day moving average price of $212.38.

MongoDB (NASDAQ:MDB – Get Free Report) last issued its quarterly earnings results on Wednesday, June 4th. The company reported $1.00 earnings per share (EPS) for the quarter, topping the consensus estimate of $0.65 by $0.35. MongoDB had a negative net margin of 4.09% and a negative return on equity of 3.16%. The business had revenue of $549.01 million for the quarter, compared to the consensus estimate of $527.49 million. During the same quarter in the prior year, the company earned $0.51 EPS. The firm’s quarterly revenue was up 21.8% on a year-over-year basis. As a group, sell-side analysts expect that MongoDB will post -1.78 earnings per share for the current year.

Insiders Place Their Bets

In other news, CEO Dev Ittycheria sold 25,005 shares of the firm’s stock in a transaction dated Thursday, June 5th. The stock was sold at an average price of $234.00, for a total transaction of $5,851,170.00. Following the completion of the sale, the chief executive officer directly owned 256,974 shares of the company’s stock, valued at $60,131,916. This trade represents a 8.87% decrease in their position. The transaction was disclosed in a document filed with the Securities & Exchange Commission, which is available at this hyperlink. Also, Director Dwight A. Merriman sold 2,000 shares of the stock in a transaction dated Thursday, June 5th. The shares were sold at an average price of $234.00, for a total value of $468,000.00. Following the transaction, the director directly owned 1,107,006 shares in the company, valued at approximately $259,039,404. This represents a 0.18% decrease in their position. The disclosure for this sale can be found here. In the last quarter, insiders sold 51,416 shares of company stock worth $11,936,656. 3.10% of the stock is owned by company insiders.

Hedge Funds Weigh In On MongoDB

Several large investors have recently made changes to their positions in MDB. Cloud Capital Management LLC acquired a new position in MongoDB in the first quarter valued at about $25,000. Hollencrest Capital Management acquired a new position in MongoDB in the 1st quarter worth $26,000. Cullen Frost Bankers Inc. boosted its holdings in MongoDB by 315.8% during the first quarter. Cullen Frost Bankers Inc. now owns 158 shares of the company’s stock worth $28,000 after purchasing an additional 120 shares during the last quarter. Strategic Investment Solutions Inc. IL acquired a new stake in shares of MongoDB in the 4th quarter valued at approximately $29,000. Finally, Coppell Advisory Solutions LLC boosted its stake in shares of MongoDB by 364.0% during the 4th quarter. Coppell Advisory Solutions LLC now owns 232 shares of the company’s stock worth $54,000 after acquiring an additional 182 shares during the period. Institutional investors and hedge funds own 89.29% of the company’s stock.

About MongoDB

MongoDB, Inc, together with its subsidiaries, provides general purpose database platform worldwide. The company provides MongoDB Atlas, a hosted multi-cloud database-as-a-service solution; MongoDB Enterprise Advanced, a commercial database server for enterprise customers to run in the cloud, on-premises, or in a hybrid environment; and Community Server, a free-to-download version of its database, which includes the functionality that developers need to get started with MongoDB.

Further Reading

Receive News & Ratings for MongoDB Daily – Enter your email address below to receive a concise daily summary of the latest news and analysts’ ratings for MongoDB and related companies with MarketBeat.com’s FREE daily email newsletter.

MMS • RSS

MongoDB, Inc. (NASDAQ:MDB – Get Free Report) CEO Dev Ittycheria sold 8,335 shares of the stock in a transaction dated Thursday, July 24th. The stock was sold at an average price of $231.99, for a total value of $1,933,636.65. Following the completion of the sale, the chief executive officer owned 244,892 shares of the company’s stock, valued at $56,812,495.08. This trade represents a 3.29% decrease in their ownership of the stock. The sale was disclosed in a filing with the Securities & Exchange Commission, which is available at the SEC website.

Dev Ittycheria also recently made the following trade(s):

- On Monday, July 28th, Dev Ittycheria sold 8,335 shares of MongoDB stock. The stock was sold at an average price of $243.89, for a total value of $2,032,823.15.

- On Wednesday, July 2nd, Dev Ittycheria sold 3,747 shares of MongoDB stock. The stock was sold at an average price of $206.05, for a total value of $772,069.35.

- On Thursday, June 5th, Dev Ittycheria sold 25,005 shares of MongoDB stock. The stock was sold at an average price of $234.00, for a total value of $5,851,170.00.

MongoDB Price Performance

MongoDB stock traded down $3.53 during mid-day trading on Tuesday, reaching $240.88. 1,773,883 shares of the company were exchanged, compared to its average volume of 2,297,158. The company has a fifty day simple moving average of $207.58 and a 200-day simple moving average of $212.18. MongoDB, Inc. has a 12 month low of $140.78 and a 12 month high of $370.00. The firm has a market cap of $19.68 billion, a PE ratio of -211.30 and a beta of 1.41.

MongoDB (NASDAQ:MDB – Get Free Report) last issued its quarterly earnings results on Wednesday, June 4th. The company reported $1.00 earnings per share (EPS) for the quarter, beating the consensus estimate of $0.65 by $0.35. MongoDB had a negative return on equity of 3.16% and a negative net margin of 4.09%. The company had revenue of $549.01 million for the quarter, compared to analyst estimates of $527.49 million. During the same quarter last year, the company posted $0.51 EPS. The company’s revenue for the quarter was up 21.8% compared to the same quarter last year. Sell-side analysts anticipate that MongoDB, Inc. will post -1.78 earnings per share for the current year.

Hedge Funds Weigh In On MongoDB

Several hedge funds and other institutional investors have recently modified their holdings of MDB. Vanguard Group Inc. boosted its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 6.6% during the 1st quarter. Vanguard Group Inc. now owns 7,809,768 shares of the company’s stock valued at $1,369,833,000 after acquiring an additional 481,023 shares in the last quarter. Franklin Resources Inc. boosted its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 9.7% during the 4th quarter. Franklin Resources Inc. now owns 2,054,888 shares of the company’s stock valued at $478,398,000 after acquiring an additional 181,962 shares in the last quarter. UBS AM A Distinct Business Unit of UBS Asset Management Americas LLC boosted its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 11.3% during the 1st quarter. UBS AM A Distinct Business Unit of UBS Asset Management Americas LLC now owns 1,271,444 shares of the company’s stock valued at $223,011,000 after acquiring an additional 129,451 shares in the last quarter. Geode Capital Management LLC boosted its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 1.8% during the 4th quarter. Geode Capital Management LLC now owns 1,252,142 shares of the company’s stock valued at $290,987,000 after acquiring an additional 22,106 shares in the last quarter. Finally, Amundi boosted its holdings in shares of MongoDB by 53.0% during the 1st quarter. Amundi now owns 1,061,457 shares of the company’s stock valued at $173,378,000 after acquiring an additional 367,717 shares in the last quarter. Institutional investors own 89.29% of the company’s stock.

Analysts Set New Price Targets

Several brokerages recently commented on MDB. DA Davidson reissued a “buy” rating and set a $275.00 price target on shares of MongoDB in a research report on Thursday, June 5th. Redburn Atlantic raised MongoDB from a “sell” rating to a “neutral” rating and set a $170.00 price target for the company in a research report on Thursday, April 17th. Barclays raised their price objective on MongoDB from $252.00 to $270.00 and gave the company an “overweight” rating in a research report on Thursday, June 5th. Stifel Nicolaus cut their price objective on MongoDB from $340.00 to $275.00 and set a “buy” rating for the company in a research report on Friday, April 11th. Finally, Stephens assumed coverage on MongoDB in a research report on Friday, July 18th. They issued an “equal weight” rating and a $247.00 price objective for the company. Nine analysts have rated the stock with a hold rating, twenty-seven have assigned a buy rating and one has given a strong buy rating to the company. Based on data from MarketBeat, the stock presently has a consensus rating of “Moderate Buy” and a consensus price target of $281.31.

Check Out Our Latest Stock Analysis on MongoDB

MongoDB Company Profile