Month: April 2020

MMS • Thomas Betts

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

While almost every engineering team has considered moving to microservices at some point, the advantages they bring come with serious trade-offs. At QCon London, Alexandra Noonan told how Segment broke up their monolith into microservices, then, a few years later, went back to a monolithic architecture. In Noonan’s words, “If microservices are implemented incorrectly or used as a band-aid without addressing some of the root flaws in your system, you’ll be unable to do new product development because you’re drowning in the complexity.”

Microservices were first introduced to address the limited fault isolation of Segment’s monolith. However, as the company became more successful, and integrated with more external services, the operational overhead of supporting microservices became too much to bear. The decision to move back to a monolith came with a new architecture that considered the pain points around scaling related to company growth. While making sacrifices in modularity, environmental isolation, and visibility, the monolith addressed the major issue of operational overhead, and allowed the engineering team to get back to new feature development.

Noonan explained several key points in the evolution of Segment’s architecture. The problems faced, and the decisions made at the time, sounded familiar to any experienced software engineer. Only with the advantage of hindsight is it clear which decisions could have been better. Noonan explained each major decision point on a timeline, and noted the pros and cons of each state of the system architecture.

In 2013, Segment started with a monolithic architecture. This provided low operational overhead, but lacked environmental isolation. Segment’s functionality is based around integrating data from many different providers. In the monolith, problems connecting to one provider destination could have an adverse effect on all destinations and the entire system.

The lack of isolation within the monolith was addressed by moving to microservices, with one worker service per destination. Microservices also improved modularity and visibility throughout the system, allowing the team to easily see queue lengths and identify problem workers. Noonan pointed out that visibility can be built in to a monolith, but they got it for free with microservices. However, microservices came with increased operational overhead and problems around code reuse.

A period of hypergrowth at Segment, around 2016-2017, added over 50 new destinations, about three per month. Having a code repository for each service was manageable for a handful of destination workers, but became a problem as the scale increased. Shared libraries were created to provide behavior that was similar for all workers. However, this created a new bottleneck, where changes to the shared code could require a week of developer effort, mostly due to testing constraints. Creating versions of the shared libraries made code changes quicker to implement, but reversed the benefit the shared code was intended to provide.

Noonan pointed out the limitations of a one-size-fits-all approach to their microservices. Because there was so much effort required just to add new services, the implementations were not customized. One auto-scaling rule was applied to all services, despite each having vastly different load and CPU resource needs. Also, a proper solution for true fault isolation would have been one microservice per queue per customer, but that would have required over 10,000 microservices.

The decision in 2017 to move back to a monolith considered all the trade-offs, including being comfortable with losing the benefits of microservices. The resulting architecture, named Centrifuge, is able to handle billions of messages per day sent to dozens of public APIs. There is now a single code repository, and all destination workers use the same version of the shared library. The larger worker is better able to handle spikes in load. Adding new destinations no longer adds operational overhead, and deployments only take minutes. Most important for the business, they were able to start building new products again. The team felt all these benefits were worth the reduced modularity, environmental isolation, and visibility that came for free with microservices.

QCon attendees discussing the presentation sounded like typical engineers joining a project with a long history. Quick remarks such as, “Well, obviously you shouldn’t do what they did,” were countered with voices of experience pointing out that most decisions are made based on the best information available at the time. One of the key takeaways was that spending a few days or weeks to do more analysis could avoid a situation that takes years to correct.

MMS • Dr Heinz M. Kabutz

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Of all the things that we could learn this month, why dynamic proxies?

Back in 1996, we could learn the entire Java ecosystem in a week with Bruce Eckel’s “Thinking in Java”.

Fast-forward to 2020 and the volume of information is overwhelming.

Java is still quite easy to learn, especially if we focus on the most essential tools. Start with the syntax, then object-orientation, flow control, collections and Java 8 streams. Design patterns hold everything together.

But there is more, much more.

To become a true Java Specialist, we need to also master the underpinnings of this great platform. How else can we develop systems that take advantage of the power of Java?

Dynamic proxies are such a tool. We can save thousands of lines of repetitive code with a single class. By taking a thorough look at how they work, we will recognize good use cases for them in our systems.

Dynamic proxies are not an everyday tool. They may come in handy only half a dozen times in our career. But when they fit, they save us an incredible amount of effort. I once managed to replace over half a million code statements with a single dynamic proxy. Powerful stuff.

This book is for intermediate to advanced Java programmers who want to get to “guru” status. It is not suitable for beginners in Java.

We hope you enjoy this book as much as I enjoyed writing it for you!

Let the dynamic proxy games begin!

Free download

MMS • Sergio

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Over the last few years, Dropbox engineers have rewritten their client-side sync engine from scratch. This would not have been possible had they not defined a clear testing strategy to allow them to build and ship the new engine through a quick release cycle, writes Dropbox engineer Isaac Goldberg.

The key requirement that ensured the new sync protocol, Nucleus, was testable was the principle of “designing away invalid states” thanks to the use of Rust’s type system. This was a clear step forward from the old sync engine, which evolved in such a way it could transition through invalid states to reach its final, supposedly legal state. The key design decision that made this shift possible was representing Nucleus state through three trees associated to consistent filesystem states: the remote filesystem state, the local filesystem state, and the last known fully synced state.

The Synced Tree is the key innovation that lets us unambiguously derive the correct sync result. If you’re familiar with version control, you can think of each node in the Synced Tree as a merge base. A merge base allows us to derive the direction of a change, answering the question: “did the user edit the file locally or was it edited on dropbox.com?”

Another key difference between Dropbox legacy sync engine and Nucleus lies with their concurrency models. While the legacy engine used threading in a completely free way, Nucleus ties all control tasks to a single thread, with only secondary operations such as I/O and hashing offloaded to background threads. For testing purposes, all background operations can be serialized to the main thread, ensuring thus test reproducibility and determinism.

The cornerstone of Dropbox testing strategy are randomized tests, due to the amount of edge cases that could arise when you run on hundreds of millions of user’s machines. To make test randomization effective, says Goldberg, it must be fully deterministic and reproducible. This is accomplished by using a pseudo-random number generator and logging the random seed used to initialize it in case a test fails. This approach makes it possible to re-run a random test that failed to investigate it further.

Every night we run tens of millions of randomized test runs. In general, they are 100% green on the latest master. When a regression sneaks in, CI automatically creates a tracking task for each failing seed, including also the hash of the latest commit at the time.

Goldberg further details how two testing frameworks used by Nucleus work. One is CanopyCheck, meant to catch bugs in the planner, the core algorithm in Dropbox sync engine, responsible to build a series of operations that can incrementally converge the three trees that represent Nucleus’ state. CanopyCheck thus generates three test trees representing the remote and the local filesystem plus the last known synced state, then iteratively asks the planner to process the trees until they have fully converged. In doing so, it enforces a number of invariants, based on an analysis of the generated trees, that ensure the final synced result is correct.

CanopyCheck leverages Haskell QuickCheck approach consisting in attempting to find a minimally-complex input that reproduces the failure for each failed test case. This approach is called “minimization” and is carried through in CanopyCheck by iteratively removing nodes from the input trees and verifying that the failure persists.

The second testing framework Goldberg describes in details is Trinity, which focuses on engine’s concurrency and specifically on race conditions. Trinity makes heavy use of mocking to interact with Nucleus in random ways by injecting all kinds of async behaviour, such as modifying the local or remote state, simulating I/O failures, controlling timings, and so on. One subtle bit about Trinity behaviour is it runs fully on the main thread along with Nucleus using Rust Futures. Trinity intercepts all futures used by Nucleus and decides which one is to fail or succeed. Trinity can also work in non-mocked state, i.e. use the native filesystem and networking, to reproduce platform-specific edge cases, albeit at the expense of time efficiency.

All in all, thanks to this approach, Dropbox engineers could rewrite their sync engine without incurring the risk of regressing a huge number of bug fixes accumulated along the lifecycle of their legacy engine. The original article by Goldberg includes much more fine detail than what can be covered here, so make sure you do not miss it if interested.

MMS • Chad Green

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

InfoQ Homepage Presentations Getting Stared with Azure Event Hubs

Summary

Chad Green shows how to create an event-processing pipeline in Azure.

Bio

Chad Green is a manager, software developer, architect, and community leader. Chad works as the Director of Software Development for ScholarRx. Over his career, Chad has managed groups from 3 to 63 people and worked on projects in a wide range of markets including healthcare, military, government, workforce management, financial services, chemical research, and electronic commerce.

About the conference

This year, we will kick off the conference with full day workshops (pre-compilers) where attendees will be able to get “hands-on” and exchange experiences with their peers in the industry.

MMS • Dylan Schiemann Kilian Valkhof

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Polypane is a powerful development web browser with many features to assist during the development of web applications and websites. We recently had the opportunity to sit down with Polypane creator Kilian Valkhof to learn more about what Polypane is, the motivation behind it, the technology used, challenges in creating the product, future direction, and much more.

By Dylan Schiemann, Kilian Valkhof

MMS • Nishant Bhajaria

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Transcript

Bhajaria: Let’s try and define what privacy means. Unlike security, and a lot of you who work in tech companies or even who do not work in tech companies have an intuitive sense as to what security means: a credit card breach, identity theft. There’s a very intuitive definition. Privacy is harder to define. In order to define it, let’s go back to several decades ago with Justice Potter Stewart. He was once asked to define what hardcore pornography meant. He said he didn’t have a definition for it, but I’ll know it when I see it, was his response. How does that help us define privacy?

A Lesson in Privacy

In order for that, let’s come back a little bit in the future and talk about me and my spouse and our first trip to meet my family after we got married. After we got married, I thought it would be a nice idea for her to actually meet my family. We flew to Mumbai, and against my advice my wife who had never gone anywhere to the east of London decided to eat some street food on the streets of Mumbai. She enjoyed it, and just as I forecast, promptly fell sick. We went to see the doctor, and it was all ok, just a case of an upset tummy. The doctor said, “Take these medicines for a couple of days and you’ll be fine.” So far no harm, no foul.

Then at the end of the appointment, right before we were done, he decides to yell out loudly the details about the prescription to his assistant who’s sitting across the room. The door’s open. He yells out the names of the medicines, then my wife’s name, then her weight, her statistics, and a bunch of other details. The guy writing the prescription got all the information but so did all the patients sitting outside. In three seconds, somebody who meant us no harm, destroyed my wife’s privacy. Justice Stewart said that when it comes to porn, I’ll know it when I see it. With privacy, you’ll know it when you lose it. Remember that when you make decisions about other people and their data. That’s a sensibility I try to bring to my job, and my teams, and my executive leadership team when I advocate for a privacy program.

Outline

Here’s the agenda for the talk with that background. First, I’ll introduce myself a little bit, talk about privacy in the context of the tech industry and the economy as a whole. Then introduce two parts of the conversation. First is, how do you build a privacy architecture when you collect data from your users and your customers? Then I’ll talk about building privacy architectures for data sharing. That is what happens when data leaves your company. You need an architecture for the collection, the intake of data, and an architecture for the exiting of data from your company. Then we’ll look at lessons, and a summary. Then I’ll take your questions if we have time at the end.

Introduction

A little bit about me. I have been in privacy for about 10 years now. I got into it when nobody else wanted to work in it. I took the job literally because nobody else wanted it, and it was an easy way to work with some smart people in the company. Some smart attorneys who I liked working with. That was at WebMD back in the day. I then started the privacy engineering program at Nike and then at Netflix, a few years ago. I ran the trust organization for Google Cloud, GCP. Currently, for the last few months, I’ve been leading the privacy architecture organization at Uber.

Privacy, Then and Now

As I said before, when I first got into privacy, it was a very esoteric, abstract concept. Now it’s a subject of memes and cartoons. When newspaper cartoons make fun of your discipline, you know you’ve arrived. I feel somewhat happy about it. There is a serious side to privacy. I do not want to be in the position of the kid. I do not want to be in the position of the president. I do not want to be in a situation where I’m surprised or I’ve surprised somebody else. There is a lot of power in data and privacy, and for far too long, we as an industry have not done very well. A lot of what we’re doing here today is about rectifying some of those mistakes but also setting us up for success so we can grow more responsibly.

Privacy: The Rules Are Changing

For far too long, there has been this unwritten contract between us and our customers. We’re going to build amazing products, our users will use those products, and they’ll give us a ton of data. We will then use that data to build better products. They will then use them. We will get more data. The virtuous circle will keep on spinning. At some point that contract didn’t quite work out very well.

Modern Companies

There are four key facts when it comes to privacy that we’re now reckoning here. A, we as businesses, and I’m assuming most of us or all of us in this room work for companies that collect data, so we collect a ton of data. There is no conceptual, certain way of how do you measure risk? How do you decide how sensitive this data is? There is no one right way to do it but most companies don’t even know where to start. As a result, we don’t always know how to protect data preemptively. We always react when there is a breach or a consent decree. It’s a very reactive science. Privacy suffers because of that, as does security, for that matter. Because we don’t do it right when data comes into our company, we don’t do it right when data leaves our company. That risk just keeps on growing. It’s a headache that you do not treat, it keeps getting worse.

Customer Trust Sentiment

The customers are catching on. If we believe that our customers don’t care about privacy, there was a PwC survey that I looked at when I was preparing for a course I taught on LinkedIn to start a privacy program, there are four key numbers that caught my attention. First, 69% of respondents believe that companies are vulnerable to hacks. Frankly, considering the headlines we see these days, I’m wondering what the remaining 31% are thinking. The number ought to be much higher. Ninety percent of respondents believe that they lack complete control over their information, which goes back to trust and transparency. Just 25% of respondents believe that most corporations handle sensitive data well. This is especially ominous, only 15% believe that we will use their data in a way that benefits them. There is this unwritten contract and that contract in order to work has to benefit both sides equitably. At some point, that balance has been horribly lopsided. These numbers speak to that.

This Trust Deficit Is an Opportunity

There is a silver lining to this. Let me talk about two more numbers in that study. First, is 72% of the respondents also believe that businesses rather than the government are better equipped to protect their data, which you might wonder why considering all the numbers we just saw. There are two insights to this. The first is, when it comes to the speed of coming up with privacy infrastructures, businesses are always going to move faster. It takes a longer time for government because of the inherent nature of government to make things happen. That’s number one.

The second thing is, we don’t have a choice when it comes to dealing with government. You can stop using certain apps, but you cannot stop dealing with the government. When I became a U.S. citizen, that naturalization process took about 11 months, I had to submit so many documents. The government wanted documentation about my maternal mother-in-law, who I never met, who died 21 years before I even was born. They wanted to know her birth certificate. At the time when she was born, they didn’t even issue birth certificates where she was born. I had no say in why that information was germane to me becoming a citizen or how it would be protected. There is an imbalance there as well. There is a reason why people want to trust us, we just need to give them a reason to. That’s a lot of what this talk is going to be about.

The second number is my real favorite one, the 88% number. Eight-eight percent of respondents said that they will willingly give us their data, if they trust us, and if they know how their data will be used and why it’s being used. It goes back to trust and transparency. There is an opportunity here, even in the lack of trust.

Lessons learned

What do we learn from all of these? Three things, first, privacy is an all hands on deck. Do not just let the legal team of the company think that it’s for them to defend. You’re there to help. Engineers, data scientists, the IT team, the security team, they all need to have a seat at the table. The second thing is, security and privacy are not the same thing. They are related, but when you have good security, privacy can begin. One depends upon the other, but they’re not the same thing. Then, think beyond breaches. Don’t just wait for your privacy program to emerge when there is a breach. Think about privacy when it comes to collecting information from your users, because that’s the first point at which the user comes into contact with your company, and it goes back to trust one more time. Also, how do you think about privacy when data leaves your company?

Privacy by Data and Design

How do you build a privacy architecture for data collection? People often talk about privacy by design, but really, privacy by design infers a lot of different things for different people. I like to think of privacy by data and design. That is, you have to think about data and the people behind the data as a first class citizen. It’s not a set of numbers. It’s a human being who trusts you with his, or her, or their data. When it comes to data classification or doing data architecture properly for collection, in my mind, there are four key steps. The first is the data classification that is part of the planning phase. The second is setting up the governance standards to protect that data, that is again part of the planning stage. The third, which I’ll be talking about in great detail, is inventory of the data. The fourth is actually executing the data privacy.

Classify Your Data – Planning

First, how do you classify your data? Data is the fuel that runs our innovation engine. If data were mishandled, there are different levels of risk depending upon what gets mishandled. The data classification is the way to express your understanding of the risks when it comes to the data you are collecting. This is a way for you to partner with your legal teams. I’m thinking about legal, privacy, security, data science, marketing, legal, business development. Everybody who has a say in how you as a company interact with your user needs to be at the table. Let me give you an example of what that would look like. Data classification answers two fundamental questions. The first is, what is this data? Second, how sensitive is it? That is, what would happen if that data were to be mishandled? Here’s an example. This is a very simplistic example of how I would do data classification. Since I’m coming from Uber, this was something we worked on at a very early stage. I’ll just focus on tier-1 here. What would be extremely sensitive if you were an Uber driver? Who you are, where you are?

I’m an alumnus of Netflix, and what you watched four days ago might be embarrassing, if somebody found out. Who you are and where you are goes to your physical safety. That is data we treat very seriously. That is appropriately labeled as tier-1 in our classification here. Other examples, of course, your social security card, your driver’s license, but anything that pins you down directly and unambiguously is tier-1. Of course, as you move up and down the tiers, that risk decreases, and the pressure to protect it also goes down a little bit. More holistically, you want to protect your data as if it’s all tier-1, because if you protect your data badly, just because it’s tier-4, you’ve created weakness and bad habits. At some point, all that creeps over to tier-1 as well. This is an exercise to measure risk, but don’t use it to undermine your protection and security mechanisms.

Set Governance Standards – Planning

Then, of course, the second step is now that you’ve classified your data, you want to come up with an internal theoretical understanding on how you would protect that data. Depending upon the tiers, you now have an understanding of this is tier-1, so we need to throw everything at it. Tier-2, maybe we can be a little more relaxed. At least come up with an internal understanding of how you would do it, when it comes to collection, when it comes to access, retention, deletion.

Data Handling Requirements

Just to go back to the left-hand side of that slide, data classification answers two fundamental questions. What is this data? What would happen if it were to be compromised? The handling requirements answer a third equally important question, which is, how would you protect the data now that you know how risky it is? These two steps are in sequence for a reason.

Data Inventory – Execution

The third step is the data inventory. This is especially important because it’s at this step that you tag the data based on the classification that you arrived at in stage one, so that you can protect it based on the standards you have set in stage two. Unless you do this step, everything you have done is only planning. Any planning without execution is just words on paper.

Classify and Inventory Your Data

This is a very basic diagram. I’ll go into a savvier diagram in the next slide. Think of this as a funnel that demonstrates how data enters your company. The far left is where a customer first comes into contact with your services. As data enters your company it grows. You infer stuff from it. It gets copied. It gets shared. You have data coming in from other sources. The size of data grows. Sometimes the data will grow faster than the size of your user base. If you want to classify and inventory your data, which you should, in my opinion, as early as possible, do it on the far left of that funnel, because if you do it later, it gets more and more expensive.

This makes the point even more. This is something I showed our leadership when we pitched for a budget, and it didn’t really need too much of a conversation, we got everything we wanted. Because unless you do data inventory before data is used, everything you have planned for falls flat on its face. You will notice after collection, we have inventory right off the bat before use happens. I’ll show diagrams later on in the presentation as to how this works.

Why Data Inventory Is Hard

Why is data inventory hard? Even if you do everything right, inventory is hard because typically you do it when there’s been a breach, or a consent decree, or a lot changes, or you realize, “This is not really working,” because you have too many customers asking for copies of their data. You typically do it late in your growth process as a company. In fact, I was talking to a few startup entrepreneurs last week. None of them had privacy hires in their first or second tranche. Typically, people like me come in when enough growth has already taken place. It’s going to be hard no matter when you do it, so better do it sooner rather than later.

Data Inventory at Uber

When it comes to data inventory at Uber, we thought of it as five logical, infrastructural steps. The first is we needed something that would crawl all of our data stores, and then discover our datasets, make those datasets and the corresponding metadata available. Then enable the addition of new metadata, because engineers always showed up at the last minute saying, “You didn’t catch my data. I need to make sure it’s tagged as well.” Then there’s a fifth step, which is actually applying all the tags from a privacy perspective. I would argue, that steps one through four, you would need to do anyways, for the sake of better data hygiene and data science, just to make sure that people can actually use their data for marketing purposes. I would argue that steps one through four should not be thought of as a privacy expense. In fact, for those of you who run privacy and security programs, talk to your data science team and figure out a way to split the cost, so you don’t have to argue for a privacy program from scratch.

How UMS Fits into the Larger Data Inventory Strategy

Our system that does data inventory is called UMS. It’s the unified metadata management service. I’ll be referring to it as UMS. This is the diagram that really explains everything that I just talked about. UMS is basically the be-all and end-all, it will crawl the datasets, discover all of them, pull those in as required. The four key numbers here are what I really want to talk about. On the left-hand side, on the top left is the legal data classification step. That was the one where you partner with legal to come up with that conceptual classification. Number two is where you convert that classification into machine-readable tags so you can apply it to the data. Number three is where you apply policies. There was handling policies you talked about. Then number four is where data is gushing in into your company. UMS is where all the tags and the attendant policies live. Number four is where all the data gets pushed in. UMS is where all the magic happens, where all the data meets all the logic in terms of protecting it. That’s something to think about in terms of how you would protect it and how to make sure that data doesn’t flow to the users before it is classified.

The UMS Back-End – A Granular View

I do want to call out the back-end a little bit more. This is a finer honed-in version of the diagram here. On the top left-hand side, you have the ability to refresh the data catalog. The data doesn’t get pulled into UMS automatically. We had to build a lot of infrastructure to make sure that there were multiple pipelines for the data to get into the UMS. We had crawlers. We had a UI portal that engineers could use, but there were multiple ways to make sure that data was available for the purposes of tagging.

Then you have the two boxes in the middle under the classifiers column. We have the ability to manually categorize the data. A lot of engineers knew exactly what they had was tier-1 or tier-2 or tier-3, and we gave you the chance to label your own data. We also have three algorithms in the middle that are very AI driven, that will do categorization based on crawling and sniffing of column names or JSON expressions. We have several ways to make sure that data inventory can happen under the classifier section. Then we don’t just take your word for it. If an engineer decides that an SSN is tier-4. It’s public, let’s not protect it. That’s obviously not going to fly. We have a Decider algorithm on the far right-hand side at the very top that will check one more time to make sure that the data is correctly tagged and classified.

This is the diagram from a different point of view. I’m calling out UMS twice, the UMS on the far top left-hand side, the second box on the left under data stores. It basically feeds the classifiers and enables that all the classifiers get information like the column name, the column type, any manual categorization that has already happened. The classifiers will use this information to do the appropriate tagging of the data. UMS is both the initial recipient of the data and also provides the right metadata information to make sure that the classification can happen correctly.

Then on the right-hand side, the column in the middle, UMS is the data store post-classification. Once the Decider is done, all the data gets spit into the Decider. Think of it this way, you have all of the infrastructure set up, you have everything that is scattered, but UMS is the only place where we want data classification and the tagging and the housing of data to happen. If you are looking at data in the UMS, it is either data pre-classification, or data post-classification. It is the only place where this happens. Let’s aim to make life easier for the engineer so they don’t have to go hunting for data that is appropriately privacy secure.

The UMS is “Privacy Central”

I was talking to a buddy of mine at Facebook in terms of why privacy engineering is hard. The innovation here is that engineers are going to do whatever is easy. You have to make it very easy for them, because if you make doing the wrong thing easy for them, they will do the wrong thing. If you make the right thing easy for them, they’ll do the right thing. UMS is privacy central. Our CEO, Dara, likes to say that we grew in a very decentralized fashion, and as a result, the company grew very quickly. In order for us to make sure that privacy is done correctly, there has to be a level of centralization. I know the words process and bureaucracy and centralization often rub people the wrong way, it was that way at Netflix and the same way at Uber as well. You have to build all this automation to make sure that privacy is centralized, and UMS is our way to do that.

Data Inventory Back-End Infrastructure

Data inventory needs two key attributes, basically. This is getting into the infrastructure. We need a way to capture the metadata as much as possible, right across our infrastructure, and we need a consistent metadata definition. Metadata management at Uber spans not just the datasets but also all the entities. The UMS captures metadata about the online-offline, real-time datasets, as well as ML features, dashboards, business metrics. It collects the lineage. Basically, anything that has anything to do with the underlying data that will instruct how that data ought to be classified, UMS has the ability to pull into the pipeline.

A Consistent Metadata Definition for Data Inventory

Because our metadata service needs to manage data across different sources, we’re talking about each data, freights, ride, someday ATG as well, which is the self-driving car. We’ve built this infrastructure to make sure that metadata gets classified the same way, regardless of what the data source is or where the data comes from, so that when it comes to being classified, it is platform and business line agnostic. Tier-1 is tier-1, so if you have a driver’s license for a freight driver versus an Uber Eats driver, it’s going to be classified as tier-1 regardless.

We use a taxonomy-like structure. In this example, it’s pretty intuitive for anybody who looks at this demonstration. The MySQL table and the relational database are defined as entity types because they are the abstraction of a physical entity. You can see that the MySQL table is defined as a relational database and the value of its name is UUID. It’s very intuitive. It’s very easy. Initially, getting this definition right, required a lot of participation from people who define the database schemas for people who had no understanding of privacy at all. You literally had people who knew privacy but didn’t know our infrastructure, and you had people who knew the infrastructure but didn’t know privacy. The key for us was, at what point does the Venn diagram intersect enough where we could understand their world and they could understand ours? That’s when we could build privacy right and they could make infrastructural decisions that would make privacy easier to implement in the company. This is a process we went through over several months.

Once the metadata is well defined, that’s when we came to the point. This is where we are coming into full circle. That’s when we knew how much data we had across the company and where the data was, and what pipelines needed to exist for what infrastructure. We built the crawlers to make sure that we could essentially tailor the push and we didn’t overwhelm the receiver so there was some throttling available. We use UI listeners. We had APIs. We had the UI that people could enter data manually. There were a ton of investments made by different teams who pitched in, who realized that they couldn’t do this manually.

Classification Techniques

This brings me to our AI categorization. This is the AI model in the middle. Remember, I showed you the two squares in the middle, one of them was the manual the other one was the AI driven. We had to make some trade-offs when it came to actual categorization algorithms. When it came to the coverage, accuracy, and performance trifecta, we couldn’t get all three. We literally had to apply different algorithms upon different pipelines, depending upon what our use case was. You will need to play around to see exactly how it optimizes. Because at the end of the day, you do not want to slow down the data to people who are making real-time decisions around who gets to get what recommendation when they look for Uber Eats, for example.

Data Inventory, High-Level Milestone

This is a bit of a rubric for how we pitch in terms of our risk when we present to the executive suite about how much data we have and what percentage of it presents a risk. It is extremely critical that you have a message that is very crisp for privacy because I have engineers who work on our teams who get down to the most granular level of detail about how the crawlers work and how this algorithm works, and it goes over the head of our executive suite. It almost looks like we’re bragging about our technical skills rather than making a case for privacy. You really want to condense your message to something that looks like this. When you have to make a pitch for investment, when you have to make a pitch for prioritization, you are making it based on numbers that are aggregated based on all the learnings and all the infrastructure you have built up. I have done it the wrong way. I’ve done it this way. This way works better every single time.

Concerns and Learnings

Private challenge number one, security is the foundation upon which privacy is built. At what point are you collecting so much data that your security infrastructure cannot keep up? There’s four key learnings and you have to look for all of these learnings as you grow your program. At what point do you have so much data that protecting it becomes prohibitively expensive? That’s something you need to think about, at what point can you not delete your way out of trouble?

The second thing is, at what point do you hit the inflection point where you stop discovering data that some engineer has tucked away in some S3 bucket because I might need it later on. When you stop getting those surprises on a regular basis, that’s when you know you’ve turned a corner a little bit.

The third is, what do you do when your ability to delete your data at scale is dwarfed by your data collection? What do you optimize for? Do you keep increasing your deletion infrastructure? Do you throw more money at it? Do you put more people on the team? Do you stop copying data? These are things you need to watch for.

The fourth thing you want to look at is, what does privacy do to help data quality? If you have so much data that you cannot delete it, that you have to keep adding infrastructure to it, at what point is your data becoming useless? When we were helping one such team at Uber, we found out that a ton of their data was basically the capture of information when people minimized the Uber app while waiting for the Uber driver. This must have been a busy day, so people were minimizing their app again and again, and that got captured. Seventy percent of the data was that blank data. It was totally junk data. We were running queries against it, logging against those queries. We were storing copies of junk data. Not only is that garbage data, it was not a privacy risk, but it was just useless data. When you run the privacy program well, and you ask those questions, you could actually end up helping your data science team. You could help save on storage costs. Don’t let the privacy program get this reputation of being a cost center or a slow down machine. You could pitch this as a way to help your business. Remember this.

Privacy Architecture for Data Sharing – Strava Heatmap

We’ve talked a lot about data collection and how you protect data on it, let’s talk about data sharing. Before we get into details, another story. About 5 years ago, I used to weigh 100 pounds more than I do right now. I was really big back then. I lost that weight by running in the morning and using an app called Strava. I still run every morning. I get up at 4:00. I run about 10 to 12 miles every day depending on when I feel like it. It’s a great app, because when you run with Strava, it lets you log your run. It lets you log your starting point, your end point. It puts a little heatmap that gives you a sense of community about who else around you is running and where they are running around you. This feature was insanely helpful, because it let me get back to good health. Turns out, it also gave some headaches to Strava, the company, and the U.S. military. Turns out five years ago, I was not the only one that was running. Our troops and our military bases across the world were running as well. A lot of you might know about this example, since it made some news when it happened.

Strava is a great company, and they’ve made a ton of progress. We’ve all made mistakes. This is not schadenfreude by any stretch. There are enough bad stories about all of our employers, so let’s not smile at them too much. This is a learning experience. What happened in this instance was you had enough service members in enough of these bases, running and logging their runs. Even at the early stage in Twitter’s life, there were enough people who were able to look at those models, connect them to external data, and identify these military bases. This is not by itself a problem because most of those bases are public, but these runs identified not just the bases but also supply routes to the bases, mess facilities, training facilities, other ways in which people were coming back and forth between those bases. In fact, with the help of other aggregated information, you could identify which service member was in which base. In fact, researchers also found out after the fact that if you blurred out the starting point of the run, and the ending point of the run, you could still identify all the soldiers, all the bases, all the supply routes, everything. Basically, because some people decided to go for a run using Strava, you had a whole bunch of U.S. security, military infrastructure, just outed like that.

Privacy Is about Data and Context

You might wonder what Strava was thinking, and they genuinely didn’t foresee this coming. When this news hit, their response was that you can change your settings to make sure that this is not broadcast on the heatmap. That’s true as far as it goes, but for those of us who work in privacy and security know, that if you have to explain how your tool works after a privacy or security issue, you’ve lost the argument. That’s just how life works. I’ve been there myself. That’s just how it is. You own the security and privacy of your data the moment it enters your company. You especially own it the moment it leaves your company, because if a third party or a vendor mishandles it, they didn’t do it, you did because you gave them the data. That’s just how the story plays out. Before you make decisions in the name of growth, in the name of adding a ton of users or making a ton of money, remember to not trade today’s headache for tomorrow’s migraine.

Privacy Architecture in Action

In order to prevent stuff like this from happening, what we have at Uber is we have a two-tiered program, we have the legal team that runs the privacy impact assessment, that is something that GDPR, CCPA, any number of standards and regulations require. On top of that, I started a program called the technical privacy consulting, which does two things. It helps the attorneys during the impact assessment, so they have somebody who’s an engineer who can help look at the ERDs and the PRDs and the design documents to understand what might happen if other people, who are less privacy aware, make bad decisions. That’s number one.

We also work with engineers more informally. If you are an engineer who finds data someplace and doesn’t know what to do with it, we will help you. If you don’t know how something might actually play out, if you need to understand what privacy techniques are available, we will informally whiteboard a solution for you well before you even write an ERD or a PRD. That informal engineer to engineer contact without any process, without any judgment, has been very helpful. It’s impossible to prove a counterfactual. I can’t stand here and tell you, “Here are all the bad things we prevented.” There is a lot of satisfaction in catching something before it becomes worse. I would recommend this model, because when we do this model, it helps us improve our internal privacy tools, because we know the things people are willing to do with data.

Third Party Data Sharing Checklist

Initially, what we do is we ask very high-level questions just to ease the team in. How are you protecting the data at rest, in transit? What is the level of granularity that you’re collecting or sharing it? How identifiable would a user be? Is there any aggregation or anonymization being applied? If there is a third party involved, are they monetizing the data? What does that transparency look like in terms of what they will do with the data?

Use Cases for Data Sharing with Cities

We’ve talked a lot about sharing but coming back to Uber, there are valid reasons why you might want to share data, even things that go beyond the normal stories of growth. Uber needs to work with city governments to get licenses to operate the cars and vehicles on the street, bikes. Cities need to know the impact on traffic, on parking, on emissions. They also need to collect per vehicle fees. They need to enforce parking rules for bikers, bikes, scooters. Although the way people drive in the city I’m not sure how well that’s working out. They also need to respond to service and maybe health outages. You need data about these cars and bikes and scooters. Again, there is a valid use case. You also need drop-off geolocation, that time to get the real-time impact on traffic during rush hour, for example. You might need trip telemetry information to find out and make sure that you are not going in no-go zones like hospitals, for example, where you aren’t allowed. You also need driver’s license numbers or vehicle plate numbers to make sure that you aren’t driving with expired plates or you don’t have an amber alert. There are real-time values to society to this data sharing.

Los Angeles and the MDS tool

When it comes to data sharing, I cannot get off the stage without talking about something that’s very contemporaneous. There is an argument going on, I obviously won’t go into the legal aspect of it. I’ll talk at a high level about the dispute that is going on between Uber and the City of LA. There are demands made by the City of LA about trip data that I believe, and the team at Uber believes are extremely invasive and not privacy centric. Let’s talk about what those are.

LA Specific Areas of Concern

The city of LA wants real-time trip tracking on their API. I have a couple of problems with it. One is, there is no real reason to have real-time data if you want GPS pings every few seconds. You don’t need that for every single vehicle unless there is a real health issue. You could be a little more selective but the City of LA sees it differently.

They want precise trip start and stop coordinates. Remember the Strava example I just mentioned a couple of minutes ago, you had troops on some of the most secure bases on the world, and they were outed even after their start and end points were blurred. The City of LA wants real-time locations. What if a city with a more specious human rights record needed that information, would we give that information away? Again, another use case to ponder over.

They also need parked vehicle GPS locations. The City of LA, unlike a lot of other cities in the U.S., they do not have privacy guidelines that are published, any anonymization techniques that we can evaluate, and they have not committed to non-monetization, that is, they could use that data for money purposes. Then of course, they might extend that to privately-owned vehicles. If you decide to drive for Uber or Lyft, tomorrow, your data might end up with the City of LA whether you want it or not. That’s what the dispute is about. I’m trying to distinguish between, at least from my perspective, what I see as a valid use case and one where I do not see it as a valid use case.

We’re defining several guidelines, and we’ll speed through a few of them in terms of how we try to anonymize the data before it leaves our company.

Data Retention Guidelines

We ask vendors and partners to document retention and deletion policies, so we can evaluate them. Even beyond that, if you look through from top to bottom, when we share with you unique identifiers, and precise times, at whatever level, you can only keep them for a very small period of time. Again, the 90 days is an example. That’s not the precise number. It varies on a case by case basis. Then if we coarsened the right data, that is, make it more approximate, you can keep it for longer. If you go down further, we look for even higher degrees of data approximations. The big takeaway from this slide is that if you have data that is very precise and very specific, you keep it for less time. If you want to keep data for longer, you make it coarsened. You got to pick between longevity and accuracy. You cannot have both because privacy always loses out when you have both.

Privacy Preservation Techniques (Uber)

We also ask that you remove any unique identifiers. If we give you IDs that uniquely identify you as an Uber driver, when you get the data as a city, for example, take out their ID and put your own. If the City of San Francisco gets breached tomorrow, the person who breaches them should not be able to identify me as an Uber driver or Huang as a Lyft driver. We should be indistinguishable basically. Then we also want you to dispose off any personally identifiable information or replace with values that are generated with a pseudorandom function like HMAC SHA-256. This is where you want a security person at the table, because these techniques may vary on a case by case basis as well.

Then we also want you to coarsen the precision of any stored data. For example, round times to the nearest 30-minute increment. If you leave at 12:22, and I leave at 12:30, it gets stored in the database as two people who left at 12:30. It’s a little more approximate. It’s only 50% more privacy, but across a vast sample set, you get a lot more anonymity that way. Then you convert the GPS coordinates to the nearest start or end or the middle of the street, or round it off to a certain number of decimal points, for example, in this case, three decimal points. Let’s assume that you’re sending a file off to somebody else, and you think you’ve done all this. I’ve gone through four slides. That’s a lot of coarsening. You’ve really beaten the crap out of this data. You got to assume that there’s got to be some privacy here.

We were doing a study on this recently at Uber and we saw this tweet, where if you look at 3 decimal points, and stacked over 15-minute increments, that’s where is what that looks like. If you have a really big campus, like a hospital, or a university campus like Stanford down the street in Palo Alto, I can easily identify that you went to Stanford and you went to one of three buildings. If it’s not a busy time on campus, if it’s spring break or if it’s the Sunday right before spring break ends, or whatever, it is pretty easy to identify you because the number of rides will be very limited. Even if we do everything that we have done so far, it is extremely difficult to guarantee privacy, or at least, you cannot just send the file out and assume that privacy is all taken care of. We are leaning heavily into k-anonymization at Uber, because it is literally the only way where before data leaves us as a company, we can come very close to guaranteeing that you have some degree of privacy.

What is k-anonymization? What we do is, we make sure that for whatever degree of k-anonymity, there have to be at least X number of other people that share all your vital attributes. If you talk about k2-anonymity, there has to be at least one more person that goes back to the example of the 12:30 ride where you left at 12:21 and I left at 12:23. If you round it off to 12:30, we have a k2-anonymity. That’s an oversimplified example, but you get the general argument.

Uber Movement Portal

We practice k-anonymity using our Uber movement portal. This is a pretty nifty tool. I use it every morning because of my commute. It basically gives you the approximate time to get from location A to location B, and this basically takes you from Santa Monica to Inglewood. In this example, this tool is useless because there were not enough rides. If we give you the average time, we’re essentially giving you the times as close to possible as maybe the three or four people that took those rides at that time. There has to be a certain number of people who took the rides for that data to be privacy centric. Also, if only two people took the ride, that data is not very useful anyways, because the average with very small numbers is pretty useless. Another example we’re doing the right thing for privacy, improves data quality anyway. Make that argument when you pitch privacy the next time.

K- Anonymity – A Case Study: 40,000 Boston Trips

In order to really give this presentation, I had somebody on my team do a case study for 40,000 Boston trips, and some interesting learnings about k-anonymity came up. I’ll caveat by saying that these might not be representative of anything you try, because this was a specific cohort of 40,000 rides in one city in the U.S. during a certain time frame. Pick 40,000 different rides and a different learning comes up.

Here’s what we found out. Look at the top row here. When you go from 0 through 5, that’s the number of decimal points we give you for the GPS, and if you go from 2 through 1000, that’s the k-anonymity. If I give you 0 decimal points, that’s pretty coarse data, that’s very approximate GPS location. At that point, I can at least for those 40,000 trips, find at least one other person, all the way to the right at least find 999 more people. All the way from k-anonymity of 2 through a k-anonymity of 1000, I have 100% coverage. It’s extremely privacy centric. The problem is, somebody in business or somebody on the data sharing side might say something saying that this data is not very helpful. You have to find a way to make sure that your data is not totally useless. At what point do you feel comfortable that there is enough privacy and make the data a little more useful?

Let’s look at the other end of the spectrum. You have 4 decimal points and 5 decimal points. Let’s look at 5 first. If you look at 5 decimal points, you’re basically giving a very precise GPS location. If you want a k-anonymity of 2, you have 68.4%, that is, for 68.4% of the users, you could find one other person with the same ride. Your anonymity rate went down from 100% in the previous slide to 68%. You literally lost a third because of the 5 decimal points. Then let’s say you shave off 1 decimal point, that as you go from 5 to 4, your anonymity goes for 2, from 68.4% to 97.4%. Basically, at that point, 97.4% of people have somebody else who meets their anonymity as well. That fifth decimal point, destroys a lot of privacy, but gives you very precise data.

Then the real problem is on the far right. If you want anonymity of 1000, and you are a very risk-averse company, if you have 5 decimal points, not even 1% of your people can be anonymized. Then if you shave off 1 decimal point you get from roughly 1% to 17.3%. That’s roughly a sixth of your population. If you have a very risk-averse legal department and you want to give 5 decimal points, that’s not going to be a fun conversation, as this diagram tells you. Again, with a different cohort, your findings might be different. I keep caveating that.

The industry best standard from everyone I’ve talked to, people smarter than me, is 5. If you look at k-anonymity of 5, that is, you want to make sure that there are at least 4 more people with that level of anonymity as you. If you have 5 decimal points, you have 35.5%, which is not great, but not terrible either. Then when you shave off that fifth decimal point, you have 93.2%. Then if you shave off one more decimal point, that is, you have 3 decimal points, you have 99.8%. You can shave off 0.2% of the data that is identifiable. You can give 3 decimal points, and you have an anonymity of k equal to 5. This is where you can have the legal team feel secure that you are not compromising privacy, you can have some level of precision of your data. This basically means that you might need to do this on a case by case basis. Everything else we’ve talked about so far is a top-level sledgehammer. It will work across all your data. When it comes to sharing a specific file, you might need to do some detailed investigation to avoid any privacy mishap later on. This was a fun exercise because we tried several different cohorts, this one was one where the numbers were very stark. I brought it here just to make the example sink in.

We have other examples as well, in terms of what we ask municipalities to do. We want them to give us their error tolerances. There are some details about what they’ll use the data for so we can use it on our side to manipulate the data so that they can use it, but we don’t have to worry about the privacy, but we don’t end up destroying their experiments either.

Data Sharing – Case Study: Minneapolis

Let’s also look at how other places do some of this data sharing anonymity. The point behind this is that there are cities in the U.S., especially, who do some of the same things we do. We’re not just uber-privacy crazy people, there are cities that replicate some of our best practices.

The city of Minneapolis, they basically get trip IDs, but even if they’re hashed they discard them. They create new IDs in lieu of Uber or Lyft IDs. They also drop start and end points, and they also round off the start and end pick-up times as well. Everything I’ve talked about, if you get pushback from within your company, you could point to the fact that other cities and other responsible third parties also follow some of the same practices.

They also restrict their data significantly in terms of APIs and table access. They do not store any data in real-time that is being used for processing that is only stored in memory. The processed data that gets stored to disk, but at that point, it is extremely aggregated and anonymized. They also round off the pick-up and drop-off start points. If you notice at the very top, that was a starting point. Then they split the three into three quadrants for these three, and they round off the pick-up or the drop-off closest to where the point was relative to the middle three. The cities have maps and they use them very well to anonymize them, at least the City of Minneapolis does.

Privacy and Precision – “Unique in the Crowd: The Privacy Bounds of Human Mobility”

We also did a recent lunch and learn on privacy and precision. The research paper is linked here. The point behind this study was, “Could your digital fingerprint identify you more than your real fingerprint?” The research paper talked about how 12 points can uniquely identify your fingerprint. You need a certain number of points. The more points you need, the more privacy centric that metric is, so 12 points for a fingerprint. They also looked at 1.5 million people over 15 months. They looked at, how do you identify those people based on their mobility traces? That is if you look at who they are, and where they are, for 95% of the people, in terms of a sample size of 1.5 million over 15 months, 4 spatio-temporal points would identify them, 95%. This makes it extremely hard when it comes to giving privacy, especially if we know who you are and where you are.

They also found out that as they made data coarser, for every 10% of precision that they lost, they only got 1% of privacy. At some point, it becomes a trade-off between how much privacy have you lost, and how much privacy have you gained versus how much data is still useful. That’s something else you’ll have to look at.

Sacrificing Time and Location for Privacy

This graph really makes the point pretty well. At the bottom left you see 80%. When you are still on the graph, at very close levels of spatial resolution, which is on the vertical axis, and temporal resolution, which is on the horizontal axis, 80% of the people are identifiable. Then you lose 40% of resolution on both sides, and you still have 70% of people identifiable. You’ve basically lost 30% of precision, and you’ve only gained 10% of privacy. Then you pull out even further at 60%. At that point, you’re almost off the charts. Then when you get from 50%, you’re pretty much off the charts. It’s only when you get to 40%, you’ll notice that the top line is to the right of the A, and the bottom line is already right above 15. The question is, inherently, there is a tension between the quality of the data and the amount of privacy you can get. Which is why I mentioned before, k-anonymity is so helpful because the idea that you can build out an infrastructure that will bail you out every single time without you looking at it is simply not real. You’re going to have to make that investment. That’s why you need a centralized privacy team to at least provide that data to your company.

This is, of course, the challenge of outside information. That is, there is information available outside the company that can help identify someone. The people who wrote the paper found out that if they looked at medical information and a voter’s list, they could identify the sitting governor of Massachusetts. They were able to identify this person, call the hospital, and get their medical record. That is how much information they were able to get.

Data Minimization

How do we solve this? We are looking at a brand new technique called data minimization. I know it almost sounds cliché, but we’re working with teams across the company to figure out a way to just start collecting less data. We’re looking at folks who write services to basically let people call Uber rides or order Uber Eats, and how do we make sure that we don’t collect things like the location, for example, in the header? We use it from the platform where we already have that location. Because if it’s in the header, it enters the system, it gets stored in other systems, gets copied everywhere, because it’s incoming data and it gets copied fresh. How do you make sure that you collect data as little as possible and make sure that people don’t have access to the data to begin with, unless they absolutely really need it? In which case, they know exactly where to go.

Data minimization is a heavy point of investment for Uber, because when you have less data, there is less data to classify, less data to tag, less data to classify and rank in terms of those ML classifications, less data to anonymize, and less data to worry about being joined with external third party data. This is something we’re leaning in pretty heavily on at Uber, and this is going to be my focus, my OKR for the next year.

Takeaways

These are the four key takeaways for the talk here. Privacy is not just for attorneys. I’ve said this many times. It’s a cross-functional discipline. Know what data you have, why you need it, tag it, inventory it early in the process as much as possible. In using and sharing data, make it as coarse as possible. Apply a whole bunch of techniques. There is no one technique that will get you out of jail. Finally, as I mentioned before, minimize your data.

Questions and Answers

Participant 1: On the UMS system, how do you handle PCI compliance and HIPAA if you’re funneling all that data through that system?

How did you select Minneapolis? Is it really just Minneapolis that is doing that across the United States, or requiring that?

Bhajaria: Minneapolis is an example they have not only done all of this stuff, but they have published a lot of this as well. The reason Minneapolis was instructive is because in a lot of our conversations with other municipalities, we point to Minneapolis because it’s often easier for municipalities to get this information from each other, rather than from a company, from a cost perspective. Also, the APIs that Minneapolis uses are also universally used by different municipalities across the country. The City of Oakland also does an amazing job as well. They have a well published one. A lot of their stuff is much deeper. In fact, there’s is even better in my opinion, although, other people at Uber disagree. They’re both extremely good.

When it comes to HIPAA that just gets run separately, HIPAA and PCI, especially some of that tokenized information because of how financially or health sensitivity it is. That is just run totally separately, because a lot of that information came in first. In fact, from my Nike days, when I found out that height and weight was being looked at as personal health data by the CCPA. That lesson was learned pretty early. This was built primarily because there was a ton of other data that also became thought of as more and more protected data. We needed something that could just manually allow people to categorize it at scale. With ML, you don’t need all that with PCI and HIPAA, you know it’s sensitive. It’s almost, let’s not make it easy, program hard. Let’s just pay the cost. We almost have that two-tiered structure.

Participant 2: I was wondering if you could speak to the political challenges, because all this, getting people to classify data, getting developers to use tools, and things like that. It requires work for them to do. I was wondering if you could speak to some of the political ways to handle that.

Bhajaria: There’s a saying that either you will pay for privacy or you will pay for not having privacy, and that cost is much higher the second time around. I’ve always been lucky. I’ve always entered companies after something bad has happened. I got into Netflix after the consent decree with the Netflix challenge. I got into Nike, just as CCPA stuff was happening. I got into Uber after the challenges the company had the last two years. Sometimes, the past makes it easier for you to be in the present. That’s part of it. Also, the company had just gone through tremendous challenges because of GDPR. It was an extremely, prohibitively expensive endeavor. It cost a lot of money. It also delayed a lot of things on the roadmap. When you can present the before and after, what it would look like, if you were to do this right now, it helps. I’ve been a product manager before. I’ve been the data collector before. I can tell people what it was like to clean this up, because I didn’t do it right the first time. You really want to have people in your team that have the infrastructure, the product experience. Don’t just fill your privacy team with policy folks, because otherwise the engineers will talk over them, and then you really won’t have that synergy. You want people who have the empathy, who understand what it is like to build these tools, and at what point these tools are actually useful. It’s not easy, but that’s how we’ve done it.

Participant 3: There is a huge amount of data coming to the organization in order of GBs of data per minute or per second maybe, in multiple rates. That is huge amount of data coming to the organization via ingestion. How do you minimize it in an efficient way, such that the next flow does not get impacted?

Bhajaria: I don’t have a whole lot to share right now, because we’re still in the ideation phase. Let me give an example when we talk to the location team. For example, if they send the location in the header, that header gets propagated literally across the company. People who don’t need the data, who don’t know that they have the data, start collecting it. They start storing it. Their jobs run against it. They log it. The real privacy challenge starts when people mishandle data that they didn’t know they had, because if they don’t know it, they don’t categorize it, they don’t do anything right with it. How do you challenge people to understand, what do you really need? You want to make sure you have people who have the architecture and the product background, because they can ask questions, “Let me help you architect this product.” I advocate for privacy, but my job is to help you build your product better. When you do that with the three or four key marquee services in the company, that information starts percolating down. Then you might break some things. When that data stops coming in, you find out who really needs it. There’s going to be a little bit of hit and miss, but you need to come at it from the architectural perspective only at the Edge layer.

Participant 3: There are multiple data providers, third party data providers, which are sending the data to my company. If they are sending the user data, then is it my responsibility to hash the data out to minimize it?

Bhajaria: My argument always is going to be, the first person who touches the data hashes it. I think your question goes to the legal policy side a bit as well. I’d hate to be an attorney. I’ll always argue for let’s hash it or let’s anonymize it as early in the game as possible. I would consult with a legal team just to make sure.

See more presentations with transcripts

MMS • Bruno Couriol

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

The open-source project HTML DOM provides over 100 snippets of vanilla JavaScript performing common DOM manipulation tasks. The tasks difficulty range from trivial (get the class of an element) to advanced (create resizable split views). The project may be useful for educational purposes, and for component developers who need to do low-level DOM handling themselves.

Phuoc Nguyen, key contributor for the project, explained the rationale for the project:

If you develop or use a web component in any framework, you have to work with DOM at a certain level.

Knowing the browser DOM APIs and how to use them play an important role in web development. A website introducing the APIs, well-known problems, most popular questions could be very useful.

The HTML DOM snippets only use the native browsers’ APIs, and as such require no external libraries. This is made possible by the standardization of the native browser APIs in every modern browser carried out by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), and the collaboration between browser vendors in discussing innovative features in platforms like the Web Platform Incubator Community Group (WICG) or the Responsive Issues Community Group (RICG).

The HTML DOM snippets are divided into three categories according to their estimated level of complexity or required prior knowledge. Basic tasks include, among other things, attaching or detaching an event handler, retrieving siblings of an element, or updating the CSS style for an element.

Intermediate tasks include: calculate the size of scrollbar, get the first scrollable parent of an element, communicate between an iframe and its parent window, download a file, export a table to CSV or load a CSS file dynamically and more.

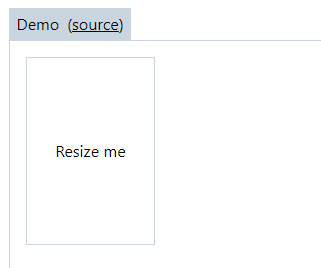

Advanced tasks include creating resizable split views, drag-to-scroll interactions, making a resizable element, sorting a table by clicking its headers and more.

The snippet related to making a resizable element is made of 20 lines of CSS, 7 lines of HTML, and slightly over 30 lines of JavaScript. The HTML includes divs for the bottom and right border handle. The CSS code handles changing the cursor when the mouse is on the HTML element’s handle. The JavaScript handles the interaction logic, and involves setting and removing mousemove listeners depending on whether the user is dragging one handle. The end result is as follows:

Some developers have expressed enthusiasm on Hacker News. One developer said:

neat resource, I’ve bookmarked it.

You know where vanilla JS still has a legitimate use-case in the era of SPAs? Landing pages.

- Mostly static HTML, time to first render is critical, all you want is a little bit of (progressively added) flair

- Can be inlined for instant loading/execution, no bundle download (or SSR) necessary

- Code has low volume and scope so structure/spaghetti isn’t a concern

- You can separate it out from the rest of your SPA bundle(s), so shipping changes is completely decoupled from your SPA CI/CD process and can be done as frequently as you like and _very_quickly

Another developer emphasized the educational value of the project:

The MDN docs are from my experience the best browser frontend reference available.

This site, however, covers a different need: guide/howto oriented documentation, which is often what you want.

HTML DOM is available under the MIT open source license. Contributions and feedback are welcome and may be provided via the GitHub project.

MMS • Sergio De Simone

Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Go’s growing adoption as a programming language to create high-performance networked and concurrent systems has been fueling developer interest in its use as a scripting language. While Go is not currently ready out of the box to be used as a replacement for bash or python, this can be done with a little effort.

As Codelang’s Elton Minetto explained, Go has quite some appeal to be used as a scripting language, including its power and simplicity, support for goroutines, and more. Google software engineer Eyal Posener adds more reasons to adopt Go as a scripting language, such as the availability of a rich set of libraries and the language terseness, which makes maintenance easier. On a slightly different note, Go contributor and former Googler David Crawshaw highlights the convenience of using Go for scripting tasks for all programmers spending most of their time writing more complex programs in Go:

Basically, I write Go all the time. I occasionally write bash, perl, or python. Occasionally enough, that those languages fall out of my head.

So, being able to use the same language for day-to-day tasks and less frequent scripting task would greatly improve efficiency. Speaking of efficiency, Go is also a strongly typed language, notes Cloudflare engineer Ignat Korchagin, which can help to make Go scripts more reliable and less prone to runtime failure due to such trivial errors as typos.

Codenation used Go to create scripts to automate repetitive tasks, both as part of their development workflow as well as within their CI/CD pipeline. At Codenation, Go scripts are executed by means of go run, a default tool in Go toolchain that compiles and run a Go program in one step. Actually, go run is no interpreter, writes Posener:

[…] bash and python are interpreters – they execute the script while they read it. On the other hand, when you type go run, Go compiles the Go program, and then runs it. The fact that the Go compile time is so short, makes it look like it was interpreted.

To make Go scripts well-behaved citizens among shell scripts, Codenation engineers use a number of useful Go packages, including:

While using go run to run Go program from the command line works well for Codenation, it is far from a perfect solution, writes Crawshaw. In particular, Go lacks support for a read-eval-print loop and cannot be easily integrated with the shebang, which enables executing a script as if ti were a binary program. Additionally, Go error handling is more appropriate for larger programs than it is for shorter scripts. For all of those reasons, he started working on Neugram, a project aiming to create a Go clone solving all of the above limitations. Sadly, Neugram appears now abandoned, possibly due to the complexity of replicating all the fine bits of Go syntax.

A similar approach to Neugram is taken by gomacro, a Go interpreter that also supports Lisp-like macros as a way to both generate code as well as implement some form of generics.

gomacro is an almost complete Go interpreter, implemented in pure Go. It offers both an interactive REPL and a scripting mode, and does not require a Go toolchain at runtime (except in one very specific case: import of a 3rd party package at runtime).

Besides being well suited for scripting, gomacro also aims to enable to use Go as an intermediate language to express detailed specification to be translated into standard Go, as well as to provide a Go source code debugger.

While gomacro provides the most flexibility to use Go for scripting, it is unfortunately no standard Go, which raises a whole set of concerns. Posener carries through a detailed analysis of the possibilities to use standard Go as a scripting language, including a workaround for the missing shebang. However, each approach falls short in some way or another.

As it seems, there is no perfect solution, and I don’t see why we shouldn’t have one. It seems like the easiest, and least problematic way to run Go scripts is by using the go run command. […] This is why I think there is still work do be done in this area of the language. I don’t see any harm in changing the language to ignore the shebang line.

For Linux systems, though, there might be an advanced trick which makes it possible to run Go scripts from the command line with full shebang support. This approach, illustrated by Korchagin, relies on shebang support being part of the Linux kernel and on the possibility to extend supported binary formats from the Linux userspace. To make a long story short, Korgachin suggests to register a new binary format in the following way:

$ echo ':golang:E::go::/usr/local/bin/gorun:OC' | sudo tee /proc/sys/fs/binfmt_misc/register

:golang:E::go::/usr/local/bin/gorun:OC

This makes it possible to set the executable bit of a fully standard .go program such as:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

s := "world"

if len(os.Args) > 1 {