Article originally posted on InfoQ. Visit InfoQ

Key Takeaways

- The topic of mental illness is often shrouded in taboo and stigma which hinders open communication and relationships.

- Opening up about your struggles can help. It can make others feel less alone and encourage them to speak about theirs in turn. But it can also help by allowing yourself to ask for and accept help.

- Speaking openly about your experiences and opinions can be daunting. But rather than a character trait, it is more of a skill that can be learned and practiced.

- Showing vulnerability, for instance by admitting to having a mental illness, is sometimes seen as a weakness. But contrarily, it can be an empowering experience – to yourself and others.

- In uncertain times like the ones we currently live through, many struggle emotionally and psychologically. By changing the way we talk about mental illness to a more open and unprejudiced conversation, we can make it easier to see the symptoms, understand them, and get help if needed.

Mental illness is a topic that does not get discussed openly very often. Many people concerned hide their own history for fear of being stigmatized, especially in the workplace. I was no exception to this, until one day I decided to speak openly, even with my boss and co-workers. Communication and relationships have changed a lot for me since then and – even though not all experiences have been positive – largely for the better. I recently told my story at the Agile Testing Days and afterwards many participants reached out to me, saying that they had had similar experiences with illness and self-imposed silence. This again solidified my belief that talking about mental illness helps yourself and others. So let me share with you what I have learned from breaking the taboo.

When I was in my early twenties and a math student at University, I fell ill. I did not know what was happening to me; I only knew things were going terribly wrong. University was not going well, my boyfriend and I were fighting incessantly and – without wanting to – I was pulling away from all of my friends. Even my own thoughts scared me; I felt sad and scared and overwhelmed and lonely most of the time, and sometimes I did not feel anything at all.

I felt so helpless that I desperately clung to the only aspect of my life of which I still felt in control: my weight. I started obsessively exercising while limiting my calorie intake, striving for a body that I hoped would satisfy my own perfectionism. But it never did. By the time I admitted to myself that I needed help, my body looked as sick and malnourished as my soul felt.

When I finally went to a doctor, I was diagnosed with depression, an anxiety disorder and eating disorder, and I spent the next years on antidepressants and in therapy. I got better, little by little, but it took time and effort.

However, this is not the story of my sickness or my recovery. This is the story of what happened when I decided to speak openly about mental health, even in the workplace. So we will have to fast forward a few years.

When I had finished my University degree and first applied for jobs, my mental health became a problem again. I felt much better but my illness had taken up so much mental capacity for so long that my studies had taken noticeably longer than they should have. So my CV looked bad and, fearing the stigma that comes with mental ill health, I did not want to disclose the reasons, least of all in a cover letter or a job interview. As a result, the job application process was challenging.

One day I decided to take a risk. I had been on an interview and had been asked – as always – why I had lost time at University and the interviewer was obviously not buying my evasive answers. I admitted to the eating disorder but nothing else, hoping that that was just enough to explain the gaps, but not so bad that he would think I would relapse under the slightest bit of pressure.

He gave me a chance and hired me, on a limited contract at first. I instantly liked the work; the atmosphere was great and I loved the colleagues. I was really happy there, and to this day I still am. But back in my first months, I was constantly worried that I would slip up and someone would find out my deep dark secret.

After my diagnosis, I had always talked rather openly about mental health (or lack thereof) with friends and family. But at work, I did not dare to. You simply do not talk about that in the workplace, I thought. I did not want to be seen as weak or vulnerable or unable to withstand stress, or even stupid, least of all by my boss. That of course meant I could not speak openly with my colleagues. The years I have spent being ill and getting better have had a big impact on who I am now as a person, and they have taught me a lot. And normally I like to share what I have learned, but you cannot share insights from therapy if you want to keep the fact that you have been in therapy a secret.

So there was always friction. On the one hand, I spent hours a day with my co-workers, working, having lunch, playing foosball or having after work beers, and I had become quite fond of them. But on the other hand, I always bit my tongue.

Then, two years ago, something changed. My colleagues and I went to the Agile Testing Days for the first time. I do not know what I expected exactly, but certainly not what I encountered: people talked about mental health. In a professional environment. At a tech conference, no less. After a talk about burnout, I asked the speaker how he had explained his absences to his boss and he answered, “The truth”. That got me thinking.

Commitment, focus, respect, courage and openness – we probably all know the Scrum values by heart. But trying to hide my own history certainly did not feel courageous and open. And could I not trust my boss and my colleagues to still respect me if they knew about my history?

As it happened, I had my end of year performance review on the very first day back at the office after the conference. My head still spinning from all the new impressions (and a serious lack of sleep), I was determined to rectify my own lack of openness. So I started the review by telling my boss the whole truth about my mental illness. And from that moment on, I talked openly about mental health whenever the topic came up, even with my colleagues.

Here is what I have learned since then:

1. You are never the only one.

When you mention illness or therapy in a casual conversation with a group of people, there is often enough someone who responds with their experiences. It is a simple matter of statistics. According to the State of Health in the EU Report of 2018, 17% of the population had a mental health problem during one year- that is more than one in six. So if the group is large enough, there is always somebody else who has had a similar experience.

It should not have come as a surprise that as soon as I started speaking about mental health issues with my colleagues, I learned I was not the only one who had been through hard times or had a loved one who had.

One day, a co-worker approached me. He said there was something that he had kept to himself and he did not want to hide it anymore, but did not know how to start talking about. With my openness, he felt safe to confide his story in me. And a short while later he talked about it at lunch in a larger group as well. Having helped someone become more comfortable with talking about themselves is one of the most rewarding experiences that I have had.

2. Openness is a habit, not a character trait

The second change I noticed was within myself. Anxiety and impostor syndrome make it hard to voice your opinions, especially if you have to contradict someone. After all, who would want to listen to silly me? Why should I be right?

In an agile team however, you have to be able to say, “Hey, I think we’re wrong here” or, “I think we should do it differently”. That is what the values of courage and openness are all about, aren’t they?

I used to think that being able to speak your mind openly and easily was a character trait that I just sadly did not have. But I have found that it becomes easier with practice. Once I had shared something so very personal, expressing my opinions about day-to-day business did not seem so overwhelming anymore. Over time I became more and more comfortable with being open. At lunch I would share a funny anecdote about therapy and during our sprint planning I would share my thoughts about the user story we were discussing, even if I thought that I might be wrong about it.

I will not pretend that it is now always easy. The anxiety and impostor syndrome did not magically disappear; it still takes a conscious effort to overcome them. But I have learned that openness, much like confidence, is like a muscle that can be exercised. When you start, it is hard and your muscles get sore. But the next time you try, it feels a little easier and the ache afterwards is not as bad.

3. There’s strength in showing vulnerability

Being a sensitive person plus having depression plus anxiety means I have never had thick skin. When I was younger, I was called a wimp and a cry baby for it. So naturally, I have always worried about conflicts at work. I never wanted to show vulnerability. But that too changed.

Even in the most harmonious, well-attuned teams, misunderstandings and conflicts occur, on a professional level as well as on an interpersonal one. And you cannot resolve a problem without accepting that there is one in the first place, and that sometimes means admitting you are hurt.

One day for example, I had a stupid misunderstanding with a teammate. He was rather new on the team, and during our daily stand-up meeting, I had mentioned a problem that I was facing. His response indicated that he thought I was not doing enough to solve it and he had to save me. I did not say anything and told myself he probably did not mean it, but it gnawed at me. I kept obsessing about it for hours. Old me would just have let it ruin my day and probably leave a dint in my confidence while putting on a happy face. But new and improved, open and talkative me did not want to. So I sent him a message saying I was bothered by what he had said and why. My therapist would have been so proud. All these hours of talking about healthy conflict resolution and here I was standing my ground, making I-statements.

We talked the problem through, sorted out the misunderstanding, and have much better communication ever since. Admitting I was hurt had not made me weak in his eyes. On the contrary, he appreciated me facing the issue.

4. Some people just don’t get it

If you break a leg, no one would ever suggest you should pull yourself together and stop having a broken leg. When you are physically ill, your body needs time to heal. Sometimes you need more than time. You need doctors and medicine and plaster casts and surgery and radiation and bandages. There is no shame in that.

But when it comes to mental illness, some people do not apply the same logic. Their reasoning seems to be that if it is your head that is suffering, it is “all in your head”. So you receive advice ranging from, “Look on the bright side”, “Just stay positive,” to “Antidepressants are bad. They mess with your brain” and, “You know you’re too skinny, so eat something. It’s not that hard.” It is for the most part probably well-meaning, but entirely unhelpful. Even worse than unhelpful, it can be dangerous. When you are constantly told that it is not a real disease, you might not see a doctor, you might not take your medicine. But it is a real disease, and it is potentially fatal. So do not laugh it off and do not make people feel bad about taking pills that could be saving their life.

So how do you deal with these people? Do you try to educate them or do you try to ignore them? I myself have over time accepted that some people just do not get it. And that has meant the end of more than one friendship. That does not mean that I have stopped caring. Not caring is not exactly an easy thing to do if caring too much is part of your diagnosis. I still try. I try to explain to people what it’s like and I try to be zen about it when that is fruitless.

5. Some people get it really wrong

I talk quite openly about very personal things. And this openness at times gets misconstrued as a cry for attention, and in particular, male attention. I do not see how you can understand “My brain does not produce enough of the happy chemicals” as being flirty, but it has happened.

One day at a party, in a discussion about openness, a man told me, “I like your openness. And since we’re all being so open, here’s what I like in bed. Oh and by the way, I have been thinking about doing that to you while you were talking.” Maybe this man did not even mean any harm by what he said. Maybe he honestly thought he was cheering me up by complimenting me. But maybe he was exploiting my perceived weakness, my “confidence issues”, and that is appalling. It is predatory behavior and I am not easy prey.

Thankfully, I have not had many of these encounters.

6. People want to help you. Let them

When my colleagues and I came to the Agile Testing Days for the first time, we were planning to fly in from Cologne Bonn Airport to Berlin Schönefeld, just over an hour in the air. The only problem was that I have a phobia of flying. When I am on an airplane, panic takes over me and I cry and yelp and hyperventilate. Obviously, I did not want my new colleagues to see me lose my cool like that, but I knew it was going to happen and there was nothing I could do to hide it.

So I decided to get ahead of the embarrassment and told one of them about my fear. But she did not laugh, she did not find it embarrassing, she did not tease. She asked, “What can I do to help?” I told her how to make a flight easier for me – distract me and remind me how to breathe in case I forget. And that is what she did during the entire flight. Not only that, but all my colleagues on that flight helped to keep my mind off of my fear, even the ones I had not briefed.

My fear of being laughed at for my silly phobia made me forget one very important thing: most humans are kind. They will want to help you, if you let them. Asking for help and accepting help can be hard, I know. But changing your perspective and looking at the effects on the person who is helping might make it easier; psychological research suggests that helping others also boosts your own well-being and lowers depression. We have probably all felt the warm glow that comes from helping others. So look at it this way: you get the help you need, they get the endorphins. Win – win! And if you are scared that people will like you less for being a burden, consider the Ben Franklin effect: a person who has helped another person before will be more likely to help them again than if they had been the one who was helped. Subconsciously they reason that if they have helped, they must like the person, and actually start to do so.

7. It makes things easier

One reason I began speaking openly about mental health was purely logistical. When I first thought about speaking publicly on this topic and wrote a proposal for a talk at the Agile Testing Days about it, I was going to say it has been years since I needed therapy or meds. But that was before the world got turned upside down by the pandemic. The threat of the virus, social distancing, and on top of it, having to battle another onset of ill health (this time physical) during the pandemic has been trying and I am considering going back to therapy. If I had never opened up about having struggled with my mental health before, would I be able to say that now? If I ever have to leave the office early to go to therapy, would I try to hide it? I do not know what I would have done, but I know that worrying about it would have taken up a lot of headspace. But now that the band-aid is ripped off, I do not have to think about it any longer.

8. Everybody should know the oxygen mask rule (although many don’t)

My favourite thing about not trying to hide my experience with illness and therapy is that I can now share what I have learned. Sometimes people ask me for the most helpful thing therapy has taught me, and I always tell them about the oxygen mask rule.

One day, my therapist suggested that I needed to stop thinking about how to make others happy and think about how I was treating myself. And it was true; I constantly worried about making my parents proud, being a great girlfriend and a good friend. But to myself I was really mean: constantly nagging, thinking of myself as a loser, starving myself and not taking care of my emotional well-being. I thought as long as I was nice to others that was okay; I even fancied myself rather selfless.

But neglecting your own happiness has nothing to do with selflessness. On a plane, the safety instructions tell you to “put on your own oxygen mask before assisting others,” because if you pass out while trying to put a mask on somebody else first, you are no use to anyone. Being kind to yourself and taking care of your emotional well-being is like putting on that oxygen mask. It is not only not selfish, it is your job. Because if you do not take care of yourself, somebody else has to. If you do not make an effort with your mental health, you will have to make an effort with your mental illness. In times of crisis, being kind is essential; to each other, yes, but also never forgetting to be kind to yourself. Give yourself air to breathe.

Talking about mental health is more important than ever.

It is about time we all get used to talking about mental health. The number of people who suffer from depression and other mental health issues has been high for years, and it will only get worse. Long after this pandemic is over, we will still have to deal with the psychological aftermath of social distancing and not hugging people, not to mention living with existential dread for months on end. These are horrible, stressful times we live in, and they are taking a toll on even the strongest of characters.

Not many will come out of this with their psyche unscathed; some will need psychological help. But not everyone will be able to get it. Some will be too ashamed, and some will not see the symptoms as symptoms. So talking about the warning signs, about what you can do to look after your own mental health and where and how you can get professional help is more important than ever.

Thankfully, mental illness is much more openly discussed now than it was thirty years ago. But the way we talk about mental illness is still influenced by taboo, stigma and stereotypes. “Mentally ill” is something that is said about “lone wolf shooters,” while in truth, the vast majority of mentally ill people are people like you and me. Odds are, you know someone who is, but maybe you don’t even know that they are. How often do people say, “I’m sorry I haven’t called. I’ve been too depressed and anxious. I’m a bit better now. Let’s have coffee!”?

Talking is both the hardest and the easiest thing you can do to change the experience of patients who suffer from mental disorders. It takes some guts to speak up, but once you do, you can help other people just by talking and they can help you in turn.

I first wrote these notes for a talk at the Agile Testing Days. Days before the conference, I was incredibly nervous. What if everything I had to say was banal? What if nobody wanted to listen? But the conference taught me otherwise. The feedback I received had me alternately crying and beaming with happiness. People approached me, saying how important they thought my words were, how they had made them think and even cry and how they had resonated with them.

Many have had similar experiences with both mental illness and with fear of being stigmatized for it. But nobody should have to suffer alone and in silence. This is why I no longer hide my history; I was lucky enough to have been met with a lot of kindness, understanding and support. This puts me in the comfortable position to be able to pay it forward.

I now realize that with every person who speaks openly about mental illness, we can chisel away a tiny little bit of the walls of taboo and shame that surround the issue. Looking back at my younger self- lost, scared and ashamed- I know that it would have made a difference if these walls had not been there. So let us normalize talking about mental health and mental illness, bit by bit.

About the Author

Sophie Küster studied mathematics at university which did not go as planned. She finished with a diploma nonetheless. Now she works happily as an agile tester at cronn GmbH in Bonn. No stranger to the universe’s gut punches, she is passionate about mental health and raising awareness and communication. She recently celebrated her first conference speaking engagement at the Agile Testing Days.

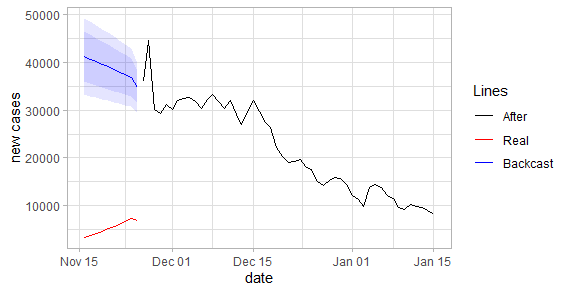

and estimate

.

with

.

with

). For instance, in this case, the model for new cases is ARIMA(0, 1, 2) with drift: